TORONTO -- Cap on head; suit that's red; special night; beard that's white.

The image of Santa Claus is one of the most famous in the world – but the infamous Christmas symbol and purported Canadian taxpayer didn't always look the way he does today.

In the early 19th century, as Santa was creeping into the public consciousness, depictions varied wildly from artist to artist. He was sometimes skinny, often short, and never associated with any particular colour.

"If you go back to some of the earliest North American views of Santa Claus … Santa is described as wearing fur from his head to his foot – nothing about any sort of colour," John Pracejus told CTVNews.ca via telephone Nov. 7.

Pracejus, the director of the School of Retailing at the University of Alberta's business school, said the head-to-toe fur originated in "A Visit from St. Nicholas," an 1822 poem well known even today for its opening line of "'Twas the night before Christmas." The poem introduced a number of other concepts that would go on to be associated with Santa, including his arrival on Christmas Eve and his eight reindeer.

Although the poem spelled out a number of physical characteristics of Santa Claus – red cheeks and nose, a snow-white beard and a "chubby and plump" stature – artistic depictions continued to vary.

SANTA CLAUS AND THE U.S. CIVIL WAR

Many historians credit American cartoonist Thomas Nast with being the first to popularize an image similar to the modern Kris Kringle.

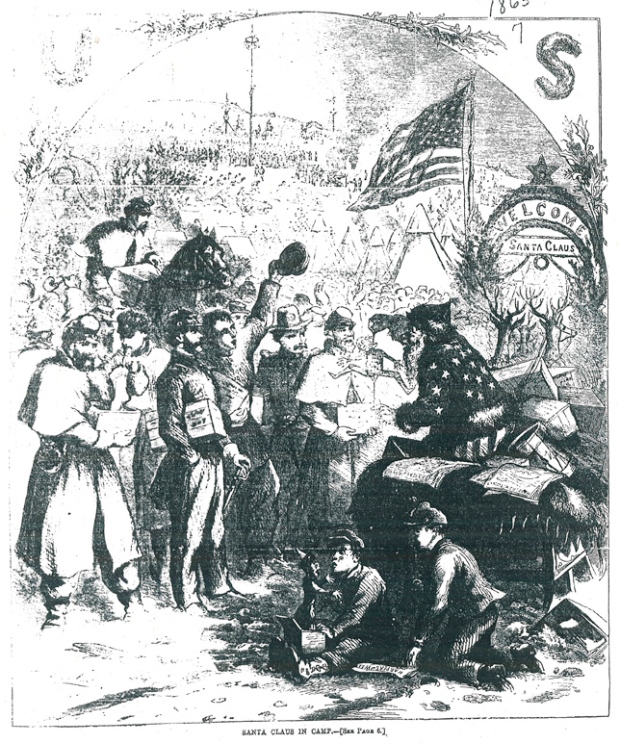

Nast, who is also reputed to have developed and promoted images of Uncle Sam, the Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey, first drew Santa in the 1863 "Santa Claus in Camp" illustration for Harper's Weekly.

This version of Santa was "a small elf-like figure, not yet the big jolly Santa Claus that he came to be," said Ryan Hyman, curator of the MacCulloch Hall Historical Museum in Morristown, N.J., in a telephone interview on Nov. 6. This Santa was also wearing a star-spangled jacket reminiscent of the U.S. flag.

Nast also popularized the idea that Santa lives at the North Pole. This claim served several purposes: It fit the existing sleigh-and-reindeer clues, it prevented any one country from claiming dominion over him, and it kept curious children from trying to find him for themselves, as no human had visited the North Pole up to this point in time.

Locating Santa at the North Pole also helped him become a sort of mascot during the U.S. Civil War. The Union used him in recruitment drives and propaganda posters, with Abraham Lincoln calling him the northern states’ best recruiting agent. A newspaper in Virginia disagreed, describing Santa as “a dutch [sic] toy-monger, an immigrant from England … [who] has no more to do with genuine Virginia hospitality and Christmas merry makings than [a racial slur for Indigenous people from South Africa]."

Nast continued to draw annual Christmas cartoons after the war ended, changing Santa's coat from star-spangled to red and further refining the character into something closer to today’s Santa Claus. The most famous of his drawings is “Merry Old Santa Claus,” which was published in 1881.

“It's Santa Claus with his big belly, toys in his arm and a backpack on his back,” Hyman said.

"That image is republished on shopping bags, billboards and all sorts of things we see around Christmas time."

Less enduring, Hyman said, was Nast’s attempt at creating a Mrs. Claus. Instead of being human, she was based on the Mother Goose character from nursery rhymes.

ENTER THE COCA-COLA COMPANY

While Nast’s contributions to the popular image of Santa Claus have been somewhat forgotten despite their popularity at the time, the role played by a major beverage manufacturer has been perhaps a little bit exaggerated, Hyman said.

It is true that, in the 1920s, The Coca-Cola Company started using Santa in its advertising campaigns during the holiday season -- a time when sales were traditionally down, as fewer people consumed soft drinks during colder weather.

"I'm sure somebody noticed the fact that Santa was often wearing red … and so they really kind of latched onto that,” Pracejus said.

According to the company’s version of events, the company’s first Santa-themed ad borrowed from Nast’s image of a “stern-looking Kris Kringle.” A few years later, inspired by a 1930 ad promoting the world’s largest soda fountain, Coca-Cola tasked artist Haddon Sundblom with depicting “a warm, friendly, pleasantly plump and human Santa.”

Advertisements featuring Sundblom’s version of Santa ran in some of the most popular magazines of the era. They became the basis of Coca-Cola’s Christmas strategy, which Sundblom helmed for decades, with ads showing Santa sometimes raiding refrigerators for Coca-Cola products and children sometimes leaving the beverages out for Santa.

"While it was probably the case that Santa's outfit was moving toward red even without that intervention by the Coca-Cola ad campaign, certainly that movement was cemented by Coca-Cola,” Pracejus said.

"It's almost impossible for people to imagine Santa wearing green or yellow anymore."

The company claims eagle-eyed fans watched its Santa ads every year, ever alert for changes such as the man in red appearing without a wedding ring or wearing his belt backwards.

Coca-Cola acknowledges using Nast’s concepts, but claims that Santa “was depicted as everything from a tall, thin man to an eerie-looking elf” before Coca-Cola standardized his image in 1931.

Hyman, whose museum sits across the street from Nast’s home, isn’t so sure.

"I think a lot of what they took really comes from what Nast had drawn years before,” he said.

Like Nast, Coca-Cola also unsuccessfully attempted to create a new supporting cast for Santa. An elf sidekick known as Sprite Boy appeared in ads through the 1930s and 1940s, even though the soft drink by the same name wasn’t introduced until 1961.