Erasing memories for nefarious purposes has figured in to many futuristic movie plots.

But now scientists in Canada and the U.S. have figured out how to delete selective memories without affecting others as a means to alleviate the suffering of those with severe anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder.

The goal is to reverse unhelpful, negative associations that can trigger symptoms in those who have been subjected to traumatic events while leaving intact memories of the events themselves, along with any useful associations.

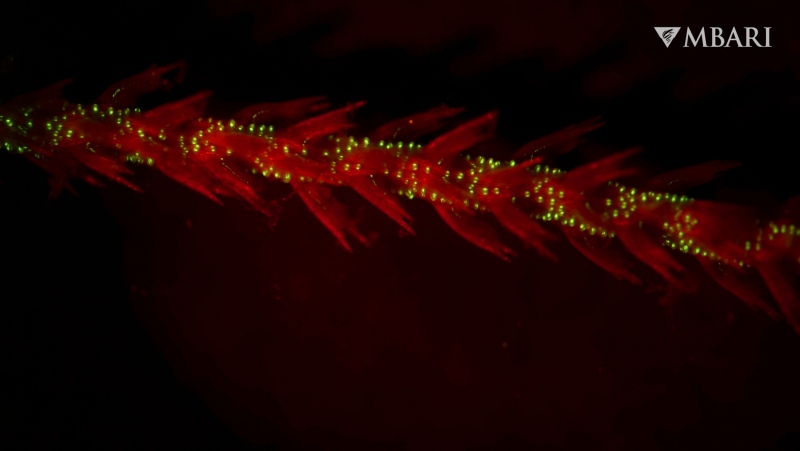

So far, researchers at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital at McGill University and the Columbia University Medical Center have worked only on snails. But they have similar memory mechanisms as humans and it’s expected trials involving people could begin in as few as five years, says Sam Schacher, a professor of neuroscience at the CUMC.

He said researchers stimulated a target neuron in snails, along with two nearby sensory neurons, to simulate different types of memories. So for instance, Schacher told CTV’s Your Morning Thursday: “You are walking in the street and you have to get from Place A to Place B. You notice a mailbox. Then you notice a dark alley that’s a short cut. You take the dark alley and you get mugged.”

One neuron is stimulated for the dark alley, the other for the mailbox, which is incidental to the experience. Each neuron is stimulated for the mugging. Each of the connections ¬– the synapses – formed by the inputs is strengthened by the encoded memory, he said.

But that mailbox memory, which has been “recruited” into the mugging memory, isn’t a helpful one when the mugging victim experiences anxiety and fear every time they see a mailbox. The fear of dark alleys remains a productive memory because the choice to head into it was directly linked to the mugging.

This research, said Schacher, showed the mailbox could be deleted by injecting drugs into a target neuron without deleting the dark alley or the mugging.

“The strategy would be something like having the individual recall that specific memory that they’re being anxious with and at the same time as administering the drug and that with time, the negative association between that stimulus, say the mailbox, and the angst and anxiety that it might produce can then be eliminated.”

While snails may seem to be a long way down the evolutionary chain from humans, Schacher says the two species have plenty in common in the enzymes and proteins of their brains.

“We are encouraged by the fact that the same molecules and the same types of processes in storing information in the brains of other animals are the same processes that take place in our brains. So yes, we’re using a snail but it’s just a model system to prove a principle, which is that we can selectively erase synaptic memories and leave others intact.”

While the research “demonstrated is a proof of principle, that it, in fact, can be done,” it will take a long time to develop a catalogue of molecules that can be targeted with existing drugs and those yet to be developed, said Schacher.

He also acknowledges there is a potential dark side to manipulating memories that needs to be addressed beyond the laboratory.