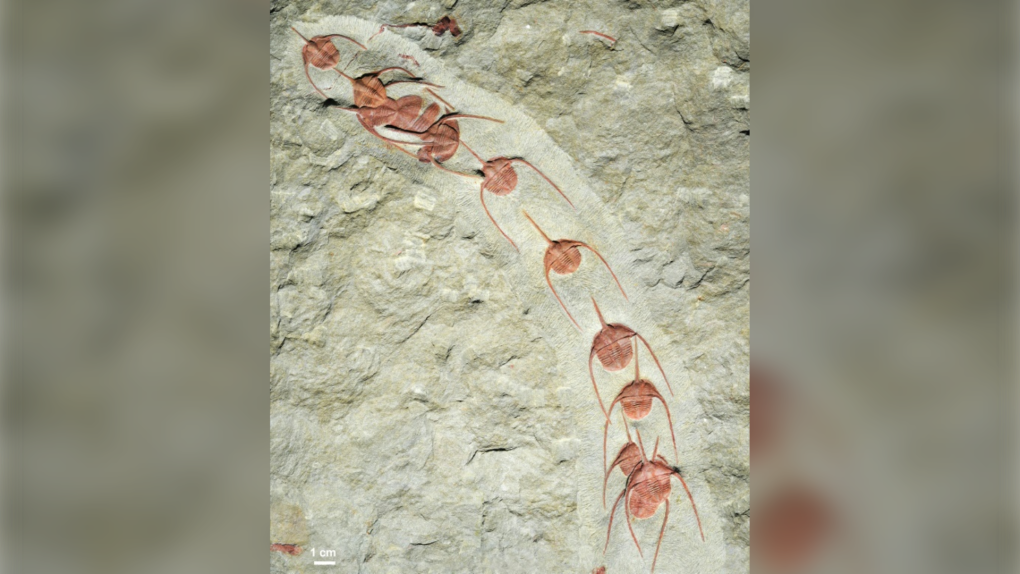

Fossils of tiny, horseshoe-shaped creatures that inched along the ocean floor in single-line formations some 480 million years ago reveal the earliest known collective animal behaviour, researchers said Thursday.

The remains of now-extinct creatures called trilobites were almost perfectly preserved in the Moroccan desert near the town of Zagora, they reported in the journal Scientific Reports.

Like all arthropods -- a phylum that includes insects, centipedes, spiders and crustaceans -- trilobites had a segmented body and an exoskeleton.

The fossil find shows a dozen of the coin-sized animals in a row all facing in the same direction, separated only by the length of two tapered spines trailing in an inverted "U" and touching the animal next in line.

"We are talking about the oldest display of organised collective behaviour in such a precise manner," co-author Abderrazak El Albani, a scientist at France's National Centre for Scientific Research, told AFP.

Group behaviour among animals -- schools of fish, flocks of birds, herds of antelope -- has been exhaustively studied by biologists, but little is known about when or how it originated.

The new find suggests two possible scenarios, the scientists said.

Touchy, feely trilobites

The primitive animals, a species called Ampyx priscus, might have been moving from one micro-environment to another to avoid bad weather.

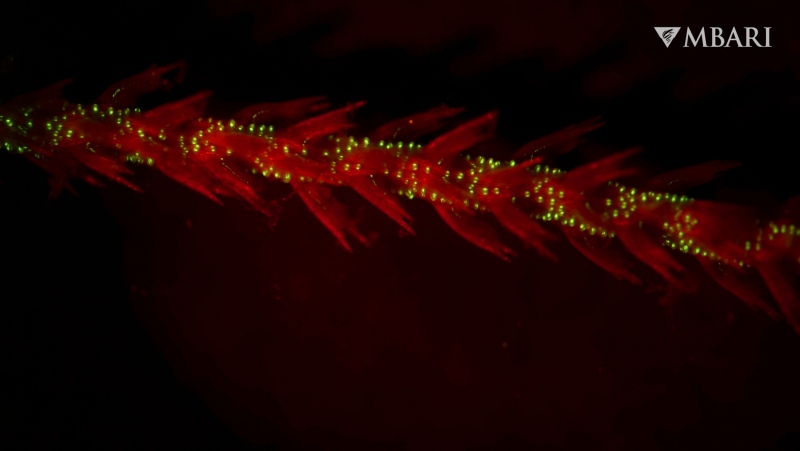

"Present-day spiny lobsters travel in single file at the onset of a storm," said co-author Muriel Vidal, a paleontologist at the University of Western Brittany in Brest, France.

"It may be a stress response to the turbulence or a change in water temperature."

Spiny lobsters -- along with caterpillars, which also travel in single file -- are distant cousins of A. priscus.

Alternatively, the orderly seabed procession could have been seasonal reproductive behaviour such as the migration of sexually mature individuals to spawning grounds, the authors suggested.

"The truth is, we know a lot more about their anatomy than we do about how they behaved," lead author Jean Vannier, a researcher at the University of Lyon, told AFP, noting that group behaviour also reduced the risk of being picked off by predators.

Whatever was driving their nose-first, single-file marches along the ocean floor, it shows "a somewhat sophisticated nervous system," he said.

"To exhibit collective behaviour, one needs an adapted nervous system that can pass signals from one individual to another," he added.

"That came into the picture very early in the saga of animal evolution."