BREMERHAVEN, Germany -- Cranes hoist cargo onto the deck, power tools scream out and workers bustle through the maze of passageways inside the German icebreaker RV Polarstern, preparations for a yearlong voyage that organizers say is unprecedented in scale and ambition.

In a couple of months, the hulking ship will set out for the Arctic packed with supplies and scientific equipment for a mission to explore the planet's frigid far north. The icebreaker will be the base for scientists from 17 nations studying the impact of climate change on the Arctic and how it could affect the rest of the world.

"So far we have always been locked out of that region and we lack even the basic observations of the climate processes in the central Arctic from winter," said Markus Rex of Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute, who will lead the 140-million euro ($158 million) expedition.

"We are going to change that for the first time," Rex told The Associated Press in an interview Wednesday aboard the Polarstern at its dock in Bremerhaven, Germany.

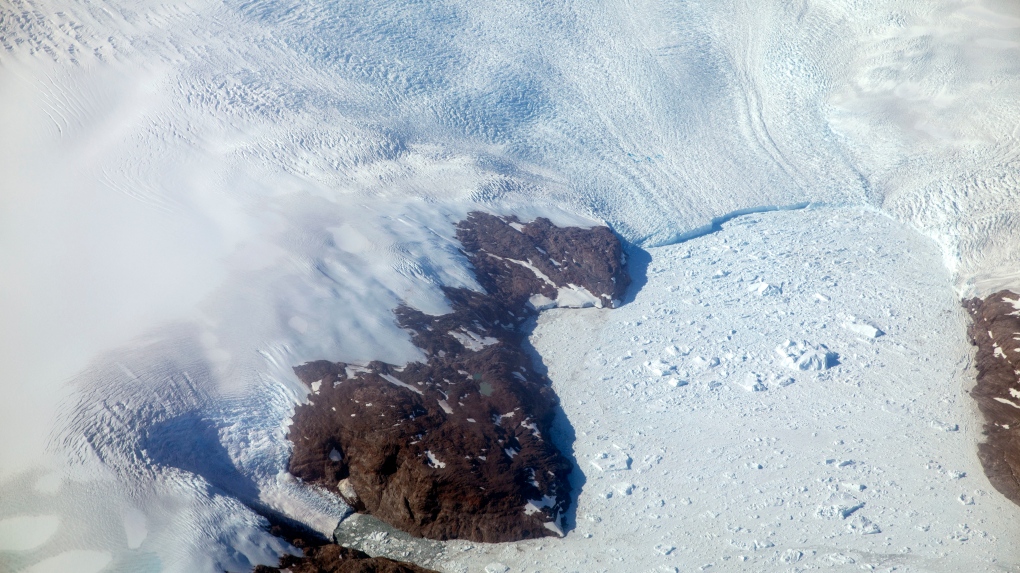

Scientists plan to sail the ship into the Arctic Ocean, anchor it to a large piece of sea ice and allow the water to freeze around them, effectively trapping themselves in the vast white mass that forms over the North Pole each winter.

As temperatures drop and the days get shorter, they plan to race time to build temporary research camps on the ice, allowing them to perform tests that wouldn't be possible at other times of the year or by satellite sensing.

"We can do a lot with robotics and other things but in the end the visual, the manual observation and also the measurement, that's still what we need," Marcel Nicolaus, a German sea ice physicist who will be part of the international mission, said. "We need to go out, establish that ice camp."

Dozens of scientists from the United States, China, Russia and other countries will be on board the Polarstern at any one time, rotating every two months as other icebreakers bring fresh supplies and a new batch of eager researchers.

The mission is considered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for many scientists, even those who are veterans of multiple Arctic expeditions.

The expedition is receiving substantial funding from U.S. institutions such as the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and NASA

By combining measurements on the ice with data collected from satellites, scientists hope to improve the increasingly sophisticated computer models they use to predict weather and climate.

The interdisciplinary work spans several fields of science, including physics, chemistry and biology. Its overarching purpose - to answer key questions around global warming - means there's no time for national rivalry, said Rex.

"The different geopolitical interests don't play a role in our research community," he said.

The mission's international collaboration and scope have drawn comparisons with the International Space Station, the most expensive and remote outpost mankind has yet created.

"Actually, we'll be farther away from civilization because the space station is in an orbit only 400 to 500 kilometres high, and we'll be much farther away," Rex said.

Once the Polarstern is carried into the depth of the Arctic night, far off the coast of northern Greenland, the scientists will be on their own, too far away for emergency evacuations by air or sea, he said.

"We'll be isolated," Rex said. "No other ice breaker can then reach us because the ice will be too thick."

The MOSAiC mission, which stands for Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, comes about 125 years after Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen first managed to seal his wooden expedition ship, Fram, into the ice during a 3-year expedition to the North Pole.

Since then, scientific understanding of the role the Arctic plays in the world's climate has grown.

Scientists now believe the cold cap that forms each year is key to regulating weather patterns and temperatures across the Northern Hemisphere. Anything that disrupts the Arctic will be felt further south, they say.

Rex cited the polar vortices that blasted cold air as far as Florida last winter and last month's early heat wave in Europe as prime examples of the impact that a change in the Arctic weather system might entail.

"The dramatic warming of the Arctic doesn't stay in the Arctic," he said, adding that understanding the processes at play in the far north is crucial if world leaders are to make the right decisions to curb climate change.

"We as scientists, I think, have the obligation to produce the robust scientific basis for political decisions," Rex said.