Canada is advising travellers to avoid non-essential travel to a specific province in Equatorial Guinea currently experiencing an outbreak of the infectious Marburg virus.

Equatorial Guinea has placed more than 200 people in quarantine and restricted movement in its Kie-Ntem province, where the hemorrhagic fever known as Marburg disease was first detected earlier this month.

As of Feb. 21, the World Health Organization (WHO) is reporting cases in nine people, including one confirmed, four probable and four suspected, all of whom have died.

"It's not unusual that we see, a week or two later, that there are more cases that appear and that emerge," Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious diseases expert at Toronto's University Health Network, told CTV's Your Morning on Monday.

"But of course, simultaneous with that you've got public health teams that are trying to quell this, trying to identify cases, trying to provide support for patients, and of course support for close contacts, informing people what to do and where to go if they think they have a suspected case."

WHAT IS THE MARBURG VIRUS?

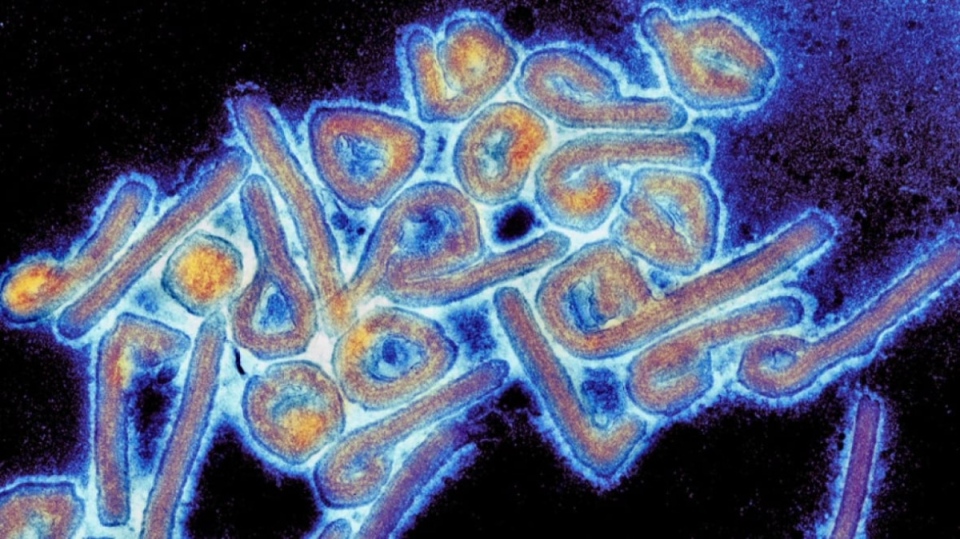

The Marburg virus causes Marburg virus disease, formerly known as Marburg hemorrhagic fever, the WHO says.

The virus is named after Marburg, Germany, where it was first detected in 1967 alongside simultaneous outbreaks in Frankfurt, Germany, and Belgrade, Serbia.

HOW DO YOU GET THE MARBURG VIRUS?

The WHO says initial infection in humans occurs through lengthy exposure to mines or caves inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies.

From there, the virus can spread between humans through direct contact with the blood or other bodily fluids of those who are infected, as well as contaminated surfaces and materials.

Improper handing of bodies at burial ceremonies, where people come into direct contact with the body of the deceased can also lead to the spread of the virus.

The WHO says all nine of the deceased cases in Equatorial Guinea were either in contact with a relative with the same symptoms, or participated in the burial of a person with symptoms similar to Marburg disease.

The virus can also be transmitted between patients and health-care workers as well as family members caring for sick loved ones.

"It's not an easy virus to catch, but it's a very severe virus to catch and it can occur when you don't have the resources to do proper bodily handling and proper care of infected individuals," cardiologist and epidemiologist Dr. Christopher Labos told CTV News Channel.

HOW SERIOUS IS IT?

While two different viruses, Marburg belongs to the same family as Ebola.

Symptoms can start between two and 21 days after infection, the WHO says, and usually come fast with a high fever, severe headache and discomfort.

Other symptoms include muscle aches and pain, followed by severe diarrhea, abdominal pain and cramping, nausea and vomiting by day 3.

Severe hemorrhage or bleeding from damaged blood vessels occurs in many patients between the fifth and seventh days, with death occurring most often between eight and nine days after symptoms start.

The average fatality rate of the disease is approximately 50 per cent, but the WHO says mortality in past outbreaks has varied between the low 20s and upward of 88 per cent, as was the case during a 2005 outbreak in Angola that killed 329 people.

Most of the outbreaks reported by the WHO since 1967 have resulted in seven or fewer deaths.

Ghana most recently declared the end to its Marburg outbreak in September, after it was confirmed the previous July. Three cases were confirmed in total, of which two were fatal.

WHICH COUNTRIES IS THE MARBURG VIRUS IN?

This outbreak of the Marburg virus was first detected in in Equatorial Guinea earlier this month. Over the weekend, Spain reported its first suspected case of Marburg disease involving a man who had recently been to Equatorial Guinea. Cameroon, which sits on the northern border of Equatorial Guinea, has also reported two suspected cases.

IS THE MARBURG VIRUS IN CANADA?

While suspected, probable and confirmed cases of the Marburg virus have been found in Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon and Spain, none have been reported in Canada or anywhere else in the Americas.

HOW COULD THIS AFFECT CANADA?

The federal government is advising Canadians to avoid non-essential travel to Kie-Ntem province in Equatorial Guinea due to the local restrictions on movement put in place to control the spread of the Marburg virus.

The border between Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon is also closed, the federal government says.

But the federal travel advisory adds that, as long as precautions are taken, the risk of contracting Marburg virus is low.

"If we take a snapshot right this minute, the risk of course is extremely low," Bogoch said. "This is really a regional issue and we should be helping and supporting our friends and neighbours around the world to quell this because obviously it's the right thing to do and it also prevents further spread."

As was seen during the 2014 Ebola outbreak — which lasted years, spanned multiple countries and killed thousands of people — Bogoch cautions the disease can spread easily without early intervention.

"It's so important to obviously do the right thing, help people locally, support the teams locally, but also it has very positive knock-on effects and helps protect the rest of the region and the rest of the world," he said.

ARE THERE ANY TREATMENTS FOR THE MARBURG VIRUS?

There are no vaccines or antiviral treatments approved for Marburg disease, but the WHO says rehydration, orally or intravenously, and treatment of specific symptoms can improve a person's chances of survival.

Labos says the lack of treatments is due to the small number of Marburg cases in the world, making it difficult to conduct trials, noting that Ebola treatments were unavailable until recently for this same reason.

"There's a lot of candidate drugs that could potentially work, but you actually have to try them before you know that they do," he said.

Vaccines are still in the development stages, and one U.S. government-backed Marburg vaccine has shown promising results in a human clinical trial.

"Supportive care makes a big difference. If you can keep people hydrated, prevent them from going into shock, that makes a difference in terms of whether somebody will survive this infection or die from it," Labos said.

With files from Reuters