A recent study found people who take a moment to consider how their actions can contribute to the further spread of COVID-19 instead of acting impulsively would almost always take into consideration the well-being of the public.

A study conducted by the University of Colorado has found that when people reflected on what consequences could stem from their actions in the height of the pandemic, they almost always cared about the public's well-being and considered what risks they could be exposing others to.

Researchers questioned nearly 13,000 people from the U.S., U.K., Austria, Singapore, Israel, Italy and Sweden. In August of 2020, the participants were asked about three hypothetical scenarios and what they valued more in those situations; the health of others or the need for social gatherings?

One of the scenarios asked what they would do if they were the owner of a small restaurant and were considering reducing capacity limits to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. The second scenario asked what they would do if they planned a party with 50 friends after months of isolation but were cautioned by health officials to avoid social gatherings over a surge in infections. Lastly, they were asked if they would consider cancelling a planned Thanksgiving celebration with 30 people, including older adults and children.

Half of the participants were asked to practice structured reflection, an exercise that would have them ask themselves how their values and morals lined up with their decisions. In the scenario about the party amid a surge in infections, 72 per cent of the participants in the structured reflection group said they would not attend, in comparison to the participants who didn't self-reflect where 67 per cent said they wouldn't attend.

When it came to the hypothetical Thanksgiving celebration, 65 per cent of respondents that self-reflected said they would cancel the party, while 60 per cent of those in the other group said they would also cancel their plans.

"Our study and others suggest it is a universal human tendency that people believe they should care about how their behaviour affects other people," Leaf Van Boven, the study’s lead author, said in a news release.

The researchers say while people can often be selfish when making impulsive decisions, taking a moment to self-reflect and continuing this practice on a frequent basis can lead to achieving public health goals related to COVID-19, the flu and other respiratory illnesses.

HUMANIZING THE SEVERITY OF THE SITUATION

As much of the world learns to live with COVID-19 and begins loosening health restrictions, the need for self-reflection has come at a crossroads for many who have begun to let their guard down because they believe there is no longer a risk involved, according to one mental health expert.

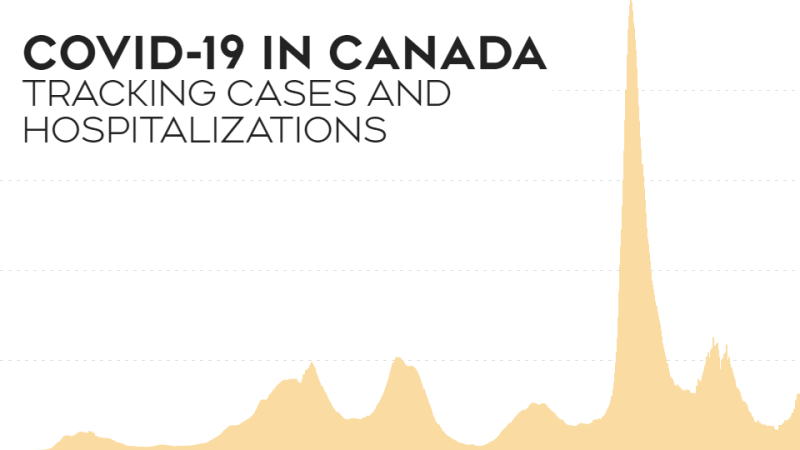

Steve Joordens, a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, says selfish thinking can be harmful, particularly now with Canada experiencing a flu epidemic and hospitals becoming overwhelmed with children struggling from respiratory illnesses.

Joordens says people aren't concerned about situations in which they aren't affected directly because they have no emotional ties to the issue. He says the emotional part of the human brain often trumps the rational side, which explains the different responses between someone who has had a loved one in the ICU with COVID-19, versus someone who doesn't know anyone personally infected.

"When a threat is only a rational threat, when it's only presented in numbers and digits, the emotional brain isn't always on board, it doesn't necessarily feel like same risk that is being told and I think that's where we see a lot of the more self-centered stuff happening," Joordens said in a phone interview with CTVNews.ca on Monday.

Joordens says without an emotional bond, people watching the news or reading public health updates won't be able to fully grasp the severity of the situation. He says this is why public service announcements that often take from personal stories can leave an impression on people who were otherwise careless about their own actions. Humanizing the issue is essential to getting people to care about a situation that may not affect them directly, he says.

"We need to be hearing from those humans who are being really negatively affected by this, whatever it may be, or in the current case, for example, if we think of hospitals that are full of children, we need to see those children, we need to hear the stories, we need to see the the fear and worry in the parents eyes to say 'this is real.'"