The federal government should invest in a publicly funded childcare system, according to a new report that claims it would increase gender equality and boost the economy.

Many Canadians are struggling with some of the highest childcare costs in the world and face lengthy waiting lists for spots, with families in Toronto paying as much as $20,000 a year for infant care, according to Oxfam Canada.

“Despite considerable evidence pointing to the benefits of child care for women’s economic equality, for economic growth and for children’s development, many governments fail to recognize child care as a public good and adequately resource it,”’ Oxfam Canada said in a press release.

“Women in Canada do almost twice as much unpaid care work than men and this has significant financial and economic impacts for women and society at large.

“Families struggle to find child care and women are forced to make difficult tradeoffs between expensive child care and their careers.”

The national average cost of childcare in Canada is around $10,000 a year, Oxfam said.

But the average monthly cost of childcare varies widely across the country:

Montreal = $175

Quebec City = $190

Winnipeg = $651

Charlottetown = $738

Regina = $845

Saint John = $868

Ottawa = $955

Halifax = $967

Edmonton = $975

St. John’s = $977

Calgary = $1,100

Vancouver = $1,400

Toronto = $1,685

“The average Ontario family spends nearly a quarter of their family income on child care, or just over two-thirds of the main caregiving parent’s potential income,” the report states.

“There is a clear need for publicly funded childcare to reduce these financial pressures on families, particularly low-income families who are working hard to escape poverty.”

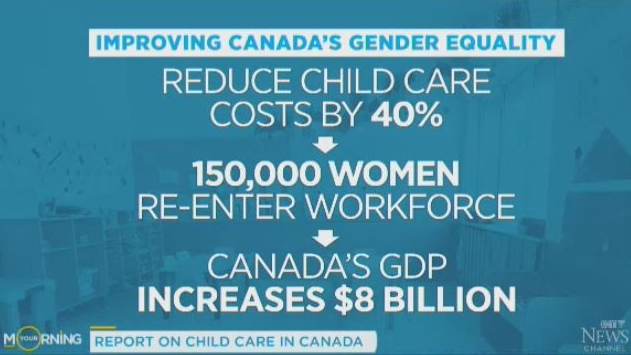

Oxfam claims if childcare costs were reduced by 40 per cent it would see 150,000 women return to the workforce and boost Canada’s GDP by $8 billion, or two per cent.

“We’re talking about a system where every single family in Canada, no matter where you live or what you earn, could have a spot in a quality daycare,” Lauren Ravon, director of policy and campaigns for Oxfam Canada, told CTV’s Your Morning.

“Families across the country are struggling, there are cities in which three kids compete for one spot in a quality daycare. In cities like Toronto families can pay up to $20,000 a year for infant care.”

In Canada, a coalition of child care and gender equality advocates, including Oxfam, have joined forces to develop the Affordable Child Care for All Plan.

It calls for a federal investment of $1 billion in 2020 and a further increase of $1 billion each year over 10 years.

“It’s not an expense, it’s an investment in the future of Canada, it’s an investment in our economy,” Ravon said.

“Every dollar you invest in childcare gets returned in terms of economic growth and growing the tax base, so it pays for itself in the long run.”

An estimated 776,000 children (44 per cent of all children younger than school age) in Canada live in ‘childcare deserts’—communities where at least three children compete for each licensed spot.

The OECD, ILO, IMF and World Bank have described Canada’s lack of accessible and affordable child care services as “one of the highest hurdles for women to participate in the labour force” and have criticized Canada’s low investment in early learning and child care, the report said.

Compared to its OECD peers, Canada ranks lowest in public spending on early childhood education and care spending, at merely 0.3 per cent of the GDP, which is well below the international benchmark amount of one per cent of GDP, Oxfam said.

Quebec’s subsidized system, unique in Canada, was held up as a success by Oxfam.

“What’s interesting in Quebec is not only has daycare become affordable for families, but it has increased women’s labour force participation,” she said.

“It has also lowered poverty rates. It’s definitely a model we can follow for the rest of Canada.”

In the past year, British Columbia has taken steps to implement affordable, high-quality and universal child care by launching a pilot program offering $10-a-day childcare.

“We know that there are so many women who work part time or not at all, not out of choice, but because they can’t get child care to keep their kids,” Ravin said.

“Every child in Canada should be able to have access to quality daycare because it’s good for them, it’s also good for gender equality and it’s good for all of us in the long run because this is the way we’re going to grow our economy in the future if we have more gender balance in the labour force and more pay equity between men and women.”

Minister of Families, Children and Social Development Jean-Yves Duclos called investments in child care in 2019 essential and said they help create employment opportunities.

“You generate more income, reduce poverty, contribute to the economic growth we’ve seen since 2015,” he said.

Duclos said his ministry would examine the Oxfam report, adding that the government is setting up an expert panel to “guide the future government’s actions and investments around early learning and child care.”

A hidden side to the childcare crisis is the conditions of child care workers, Ravin added, who are struggling with low wages and undervalued work, resulting in low retention rates, low levels of job satisfaction and labour shortages.

Oxfam Canada’s report titled, “Who cares? Why Canada needs a public child care system,” is available here.