TORONTO -- Canada doubled its rejections of permanent residence applications under humanitarian grounds, from 35 per cent in 2019 to nearly 70 per cent in early 2021, according to new data released Tuesday by the Migrant Rights Network. Advocates are calling it a “grave concern” that disproportionately affects racialized, low-wage migrants.

“Permanent residence status is the only mechanism to ensure migrants have equal rights. By doubling rejections, Prime Minister Trudeau is doubling the potential for exploitation,” Syed Hussan, the Migrant Rights Network Secretariat, said during a video press conference on Tuesday.

“The simplest first thing to do is regularize and give permanent residency to all migrants already in the country, including undocumented people. Instead, we see immigration officials arbitrarily doing the opposite,” he said.

At issue are immigration applications made under humanitarian and compassionate grounds. These grounds include discrimination in the applicant’s country of origin, having spent a long time in Canada working or volunteering, and raising a child whose life is rooted in this country.

Toronto-based immigration consultant Macdonald Scott called these residency applications on humanitarian grounds “a last resort for women fleeing gender violence, homeless people, and other undocumented families.”

According to newly-released data, in 2019, the Canadian government rejected 35 per cent of 10,600 of such applications. In 2020, this rejection figure spiked to 57 per cent of the 11,000 applications. And between January and March of this year, around 70 per cent of the nearly 9,000 applications were tossed out.

As for the number of applications being accepted, the number dropped from 5,075 in 2019 to 3,735 in 2020. The data was obtained through an order paper request from NDP immigration critic Jenny Kwan.

A spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada said COVID-19 played a role in the figures.

“The reason the number of refusals appears higher than approvals is because of COVID-related delays and the facilitative policy to grant extensions for submissions, which impacted our ability to finalize cases that were pending approval,” Peter Liang said in an email to CTVNews.ca.

“When an H & C application is approved in principle, further assessment is then undertaken to determine admissibility, which requires the applicant to submit additional documentation and to complete a medical exam,” he added, saying this aspect can cause approvals to take longer to finalize than refusals.

“As a result of COVID, applicants have encountered delays in obtaining these additional required documents, which in turn delays the finalization of their application. On the other hand, when an application is refused, no further assessment is required, which is why the number of refusals has not been impacted in the same way.”

Liang said this in turn means “these COVID-related delays in receiving necessary additional documentation and medicals have resulted in approval rates to appear lower than they actually are.”

Immigration to Canada was drastically reduced due to the pandemic in 2020, according to figures from Statistics Canada.

Canada welcomed 40,069 immigrants in the first quarter of 2020, which is 61.4 per cent less than the same period in 2019 – but reported a net loss of almost 66,000 non-permanent residents, a December report says. Toronto-based immigration lawyer Nastaran Roushan told CTVNews.ca at the time the biggest reason for this was visa office delays, as most locations shut down operations during lockdowns.

Last year, to make up for the drop, Canada pledged it would be aiming to have 401,000 new permanent residents in 2021.

'PROCESS CHOKING THE LIFE OUT OF US': MIGRANT

The permanent residency claim of Queen Gabriel, a Toronto-based elder care worker from the Caribbean, was rejected in October, 2020.

“There is no living without status in Canada, there is only existing. The immigration process is slowly choking the life out of us,” she said at the virtual press conference, calling for urgent change. “Many of us have died not being able to access simple health care during COVID-19 or even sick days for fear of unreasonable reprimand. Permanent residence should not be such a trying, nerve wrecking, daunting, undertaking for anyone.”

Many migrants don’t fit the criteria for a refugee or asylum claim, which is primarily based on fear or risk of persecution, the immigration consultant said at the press conference.

And Migrant Rights Network organizers said hundreds of thousands of undocumented migrants -- many who arrived on temporary permits which weren’t extended -- have few other pathways to permanent residency besides the humanitarian and compassionate claim.

“An agency application is the only opportunity for half a million residents to have a shot at getting basic labour rights, health care, and access to social support that permanent residence status provides,” Hussan said.

Scott, who works at Toronto-based law firm Carranza LPP, noted in a press release that the process for a humanitarian and compassionate claim can take three to five years, cost thousands of dollars and final approval “comes down to a single decision maker, with no guaranteed avenue to legal appeal.”

“No one knows how or why the decision was made to suddenly increase refusals, and that makes it hard to challenge. This has made an already arbitrary policy much worse, and with a very serious human cost,” he said.

Hussan doubled down on advocates’ longstanding call to give full and permanent immigration status to all migrants, saying that existing government programs leave out too many people.

In May for example, his group said the feds’ plan to give 90,000 temporary workers permanent residency leaves out thousands of undocumented residents, migrants and essential workers. Hussan also noted that the health-care workers’ permanent residence pathway, which was announced in January, also leaves out many undocumented workers.

Others have criticized the government’s plan to give residency to “guardian angel” asylum-seekers, as it limits eligibility only to those asylum-seekers providing direct patient care in hospitals and long-term care homes.

'ANY TIME THEY CAN CALL ME BACK': MIGRANT WORKER

When it came to humanitarian and compassionate claims, Hussan said “there is a clear systematic pattern of rejection over the last two years” which primarily affected racialized, working-class applicants.

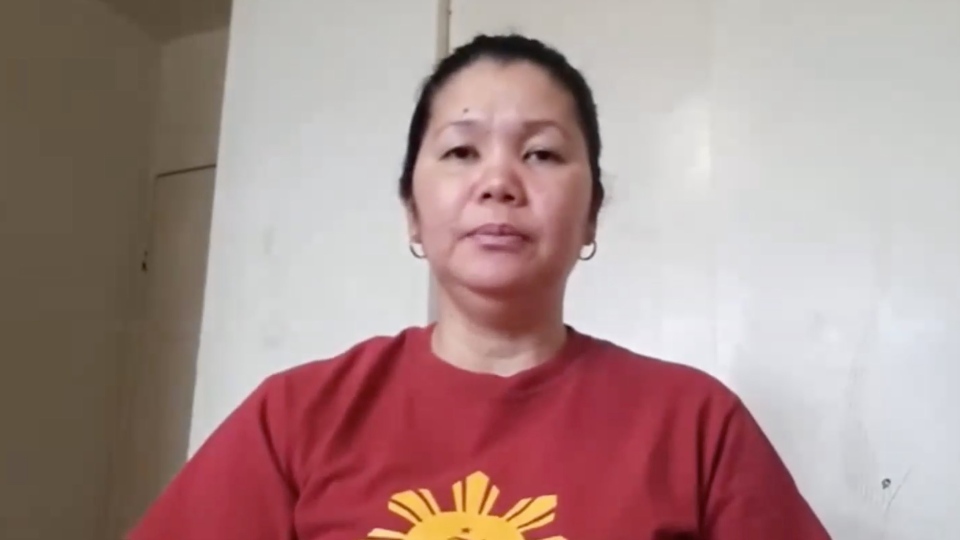

Marisol Bobadilla in Toronto has relied on short-term legal solutions to work and stay in the country since migrating here from the Philippines nine years ago. But she said her rejected claim shows the current criteria is too exclusionary.

“Most of the working class, especially the undocumented workers have been neglected and not included in permanent status [policies],” she said, calling that unfair as “each one of us experiences hardship and sacrifice.”

Lorlie Pude, a custodian at a public school in Edmonton, has been living in Canada since 2012 and said her hometown in the Philippines isn’t safe for her. She’s scared for her future as her latest humanitarian and compassionate claim for permanent residency was rejected earlier this year and her open work permit expires later this month.

“Any time they [the Canadian government] can call me to go back home because my open work permit doesn’t have [permanent] status,” said Pude, who’s also a member of the migrant advocacy group Migrante Alberta. “So I’m worried about my daughter who’s seven years old and who’s already adapted to life in Canada.”

Vancouver health-care worker Laura Lopez shared similar concerns, as her young family has been living in the country for seven years. She said they’ve spent much of their savings and downtime applying for various legal ways to stay in the country.

“My older daughter has lived here most of her life. She feels like Canada is home,” she said, noting that her child gets frightened at the thought the family will have to return to Mexico.

Lopez urges the government to do more as she fears they’ll have to “start from zero” after living close to a decade in Canada.