“Please stop. I don’t want you to send any investigation or warrants out,” the sweet voice of an “80-year-old woman” can be heard saying over the telephone.

The voice belongs to “Granny Edna,” who has just found out she owes the IRS more than US$3,000. A calm man with a South Asian accent has been trying to explain to her that she needs to make a payment if she wants the warrant for her arrest cancelled.

“You must be familiar with the Google, ma’am. The Google card? The Google Play card. Have you heard it?” asks the man, who say his name is Leo.

Edna says, “No. What’s that? I’ve never heard of Google Play. Is that a new sport?”

More than an hour into the call, Leo’s once-calm demeanour devolves into aggressive shouting.

“I’m sending the cops right away! Get yourself turned in right away,” Leo tells Edna.

This is the moment livestreamer Kitboga and thousands of viewers have been waiting for: the reveal. Dropping his façade, the man posing as Edna confronts the tax scammer about the ruse to bilk an innocent old woman out of her hard-earned money.

He reveals to the scammer that he was never chatting with an elderly woman.

“It was a pleasure wasting your time, but please consider doing something else,” he implores the scammer, who immediately responds with “no.“

This is what’s called “scambaiting” and it has thrusted the American streamer into the Internet limelight.

In nearly two years, Kitboga, who requested his real name not be used for reasons that will become incredibly obvious, has gained more than 241,000 YouTube subscribers and more than 354,000 followers on Twitch, an online streaming platform. He streams on Twitch almost daily.

“A lot of times I take on different personas and act like, maybe, an older person who’s clueless about computers or somebody who’s afraid the IRS or CRA might actually have some sort of legal action against them,” he told CTVNews.ca over the phone.

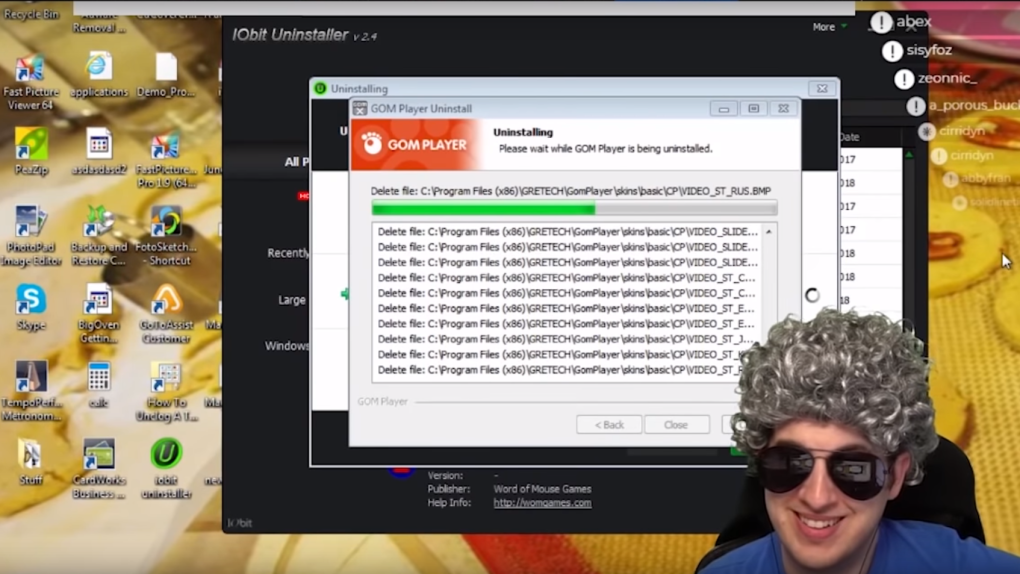

One of the many characters he takes on is Edna, an elderly woman who is often hard of hearing and loves to talk about her grandchildren. Wearing his trademark sunglasses, he puts on a grey curly wig and uses a voice changer to help him get into character.

“She can get away with just about anything because the scammers typically believe she’s maybe 80 years old or something. She’s probably one of my favourites for that reason.”

Last month, Kitboga’s Edna persona managed to keep a group of scammers on the line for eight hours on two different days as they tried to gain access to his fake bank account.

“These scammers would just stay on the phone and argue with people all because they thought they were on the phone with an 80-year-old woman.”

But Kitboga’s list of personas extends beyond just Edna. There’s Viktor Viktoor, whose confusion is often translated through an incredibly unbelievable fake Russian accent, and Neveah, a Valley girl who rarely understands what’s going.

“I just try to be a Valley girl. You know, I like makeup. Frankly, I don’t understand a lot of that world. I just go for it anyway,” he says.

EXPOSING HOW THE SCAMS WORK

Over the course of more than 1,000 calls streamed live online, Kitboga shows, in real-time, the tactics and lengths scammers will go to in order to steal money.

It’s not that scammers have a penchant for Kitboga, in fact, he’s the one who often goes in search of them. Many of the scams he finds can be located through some easy searches online – even his viewers provide him with numbers from time to time.

Many of the calls Kitboga deals with have to do with tech support scams. These often involve a pesky pop-up message that claims a person’s computer has been infected with a virus.

After establishing a call with the fake tech support agent, Kitboga has them unwittingly connect to a virtual machine, which is basically software that appears, to the scammer, to be a real computer.

Using his background in software engineering, he’s created the perfect virtual machine for trolling scammers. One of the simpler additions he’s made is a file labelled “nudes” that contains images not of lewd acts but of naked mole rats.

He says the tactics he uses provide some often scary insight into how scammers treat people.

“They’re not afraid to pull up your camera or lock your computer and start looking through your pictures to see if they can find something.”

In some of the tax scam calls he’s taken, Kitboga has pretended to drive to drug stores, even adding in small sound effects like windshield wipers moving or low-playing music to bolster the illusion.

“For me, every single phone call is a learning experience and I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

There’s always a point in the call when the scammer either gets tired of trying or Kitboga pulls back the curtain to unveil he’s been wasting their time, sometimes for hours.

“There’s categories to the way they respond. Some of them just sigh and you can feel this moment where they go, ‘Oh, I just wasted two hours’ and then they hang up and that’s it. Others get very angry and resort to screaming various racial slurs or just swearing and cursing at you, saying they’re going to come after your family and stuff.”

Last year, during one call in which he posed as Edna, an IRS scammer threatened to put a bullet in her head in order to pressure her into handing over US$6,000.

“When I started to reveal and started to say this isn’t legitimate, there were a couple IRS tax scammers who actually threatened to come kill her and that was unreal. They were actually saying ‘do you want to die? The police are going to come to your house, we’re going to put a bullet in your head, you owe us money.’ The whole call he was trying to scare me.”

CANADIANS SCAMMED OF MILLIONS OF DOLLARS EACH YEAR

Aggressive and threatening tactics are staples in the scammers’ playbook.

According to the the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC), scammers who pose as agents with the Canadian Revenue Agency will often claim their victims owe money and are at risk of being arrested.

While it may be hard for some to fathom how people fall victim to such scams, Canadians are swindled out of millions of dollars each year.

Based on data from the CAFC, an estimated 1,500 people reported being the victim of a CRA scam in 2018. It’s believed they were scammed out of more than $6 million.

Kitboga knows all too well what it’s like to have a loved one taken advantage of. Before becoming the internet star he is now, his grandmother fell victim to several scams.

“They had a landscaper that would come out to the house multiple times a week to mow the lawn and to do odd jobs around the house, and they would just pay for it.”

He says another woman would even come to his grandmother’s house to clean “viruses” off her computer.

“It just became this point, and this is probably common, but my mother, some of her family had to take control of some of her finances.”

HOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF FROM A SCAM

The CAFC website’s number one security recommendation is to hang up on suspicious callers. Kitboga echoes their advice, warning that scammers try to “socially engineer” their victims’ emotions.

He recommends hanging up the phone, taking a deep breath and contacting someone you trust.

“Even if it was actually the IRS or the CRA and you’re actually in trouble, it’s OK to hang up and wait a minute and call your parents or your lawyer or someone you trust and respect and say ‘OK this is happening to me, what do you think about this situation?’”

He also recommends reporting phone numbers when you get a scam call. The CAFC has a dedicated phone number and section on their website where people can report scams.

“There’s a legal process. Even if you actually did owe thousands of dollars to the government they’re not going to call you and say ‘You’re going to jail today if you don’t pay.’”

What Kitboga doesn’t recommend is letting scammers connect to your computer in the hopes of scambaiting them and wasting their time like he does.

“If you let them on your computer and you don’t know what you’re doing, they will own your computer and all of your information on there.”

That’s why he doesn’t post tutorials explaining how he does what he does, “in fear that some young kid might only read half of it and get himself hurt.”