TORONTO -- Over the last fifteen months, have you found yourself performing an awkward, stilted wave on a Zoom call as your other hand searches for the “leave call” button?

If so, you’re far from alone. Dubbed “the Zoom wave”, this habit of signing off on video calls with a little wave that has increased during the pandemic is one many on social media have commented on, wondering why they do it, and why it feels strange.

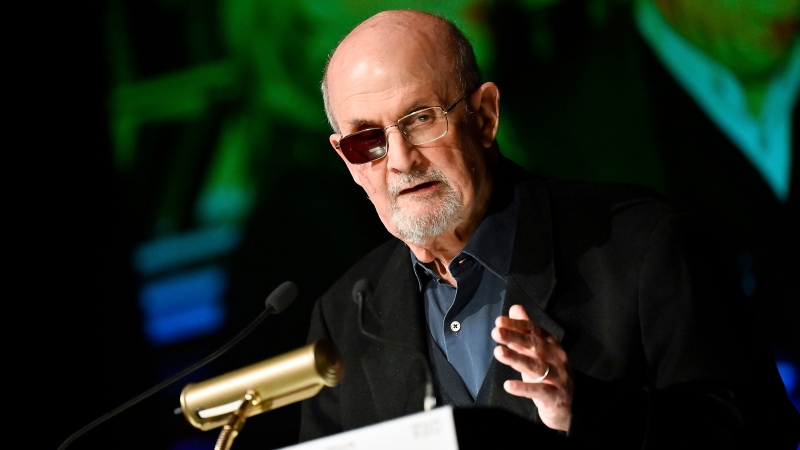

The wave is just part of our evolving body language in an increasingly virtual world, according to Erica Dhawan, author of “Digital Body Language.”

“Digital body language [is] the cues and signals we send in our digital communication that make up the subtext of our messages,” Dhawan explained to CTVNews.ca in a phone interview Wednesday. “Everything from our punctuation to our response times, to how we greet, sign off on email, to even our virtual video call backgrounds. [These] are signals and cues that either make or break trust, whether we know it or not.”

Body language is an important part of communication, she said.

“Research shows that up to 75 per cent of face-to-face communication is nonverbal,” Dhawan said. Body language, pacing, positive gestures, tone. It's not what we say, but how we say it.”

She added that even before the pandemic, a huge proportion of our interactions were taking place online.

“Up to 70 per cent of teamwork was already virtual. We were on emails. We were in conference calls, even in the office. We were emailing team members on the same floor,” she said. “And that has just simply shot up to 100 per cent [in the pandemic].”

Within weeks of the pandemic striking North America with full force in March of 2020, Zoom had emerged as a frontrunner of video conferencing apps, as workplaces moved to remote working and families and friends sought to stay in contact even while in lockdowns.

Now, a year later, Zoom is ubiquitous enough that saying you have a “Zoom meeting” or will be “hanging out with friends on Zoom later” is instantly understood to refer to video chatting.

“Prior to the pandemic, much of our digital body language was exhibited through our email, texts and phone calls,” Dhawan said. “Today, much of the way that we think about digital body language is on video calls.”

But although video chats help us talk to colleagues and stay connected with friends, it has its challenges.

“One of the things that we've struggled with is that sense of the entrance and the goodbye in an office,” Dhawan said. “We would smile at each other. We would have a firm handshake. We used our body language cues to signal a beginning and an end — now on a video call, it's much harder to showcase that signal.”

In some ways, she explained, we have to go back to basics.

“When we were in preschool, […] because children couldn't read all of our verbal cues, we would use body cues to signal that we were leaving,” she said, referring to the exaggerated waves that adults often use with small children to communicate a farewell.

“In a similar way, we're kind of like in the pre-school phase of Zoom still. We are waving […] to reinforce what we really mean. And I think what was implicit in traditional body language now has to be explicit in digital body language.”

The way we keep our hands close to our head and shoulders during a Zoom wave, in order to ensure that our hand is visible on-screen also contributes to the feeling of awkwardness, because it feels like a “baby wave,” Dhawan said. “I think that's what makes us feel so childish as well.”

Another aspect is that we aren’t physically going anywhere. Instead of waving as we walk away, we wave, click a button, and are still sitting there in the same spot at our desk, or on our couch or bed, disrupting the physical pathways we associate with a wave.

Zoom can also feel unnatural because if our camera is turned on for the conversation, we can see ourselves the whole time.

“It's not natural to look at ourselves on the screen and look at other people,” Dhawan said. “We never did that in face to face meetings. We only did that when we looked in a mirror. So when it comes to some of these dynamics, there was a Stanford study that showed that fatigue is higher for women. And a lot of that had to do with the self-gazing and women feeling that they needed to look prettier.”

Studies have shown that Zoom has even contributed to a rise in dysmorphia that drives some to seek out cosmetic procedures because they’re picking problems out of their distorted digital reflection.

Apart from making us feel bad, it affects communication.

The gallery function, which allows you to see everyone at the same time in a grid, can also turn meetings into a stressful situation where it feels everyone is staring at you — making it harder to have natural body language.

To communicate better through video conferencing, Dhawan has a few key suggestions.

“Number one, try to minimize thumbnail of your own video, stop looking at yourself,” she said. “Number two, if you're trying to build a good impression with someone, look into the camera, […] especially at the beginning of a meeting, and then look down and read their body language.”

Another thing that the pandemic has changed in the way we communicate is that with many people working remotely, and many still spending a lot of time in their homes due to pandemic restrictions, there’s an expectation that people are always free.

“Email response time expectations are faster. Texting feels faster, even getting on a call with someone feels faster,” Dhawan said.

“We have to be careful […] with the faster pace that has really been amplified by the anxiety of the pandemic and digital communication. It is very easy to prioritize hastiness over thoughtfulness.”

One of the problems is that a pause on a Zoom call feels like a mistake — like someone is on mute, or the silence needs to be filled immediately. In person, those pauses wouldn’t feel so awkward, and are essential to good communication.

"We all know that in the past, the stroking of the chin or the leaning in, or the direct eye contact or the smile gave us time to think and process information,” Dhawan said.

Regarding work Zooms in particular, she recommends that managers and meeting hosts plan out the goals of the Zoom ahead of time in order to allow people to prepare since the mode of communication is so different than the fluidity of in-person.

“You can't just hop in a room and read everyone's cues and [be] engaged,” she said. “You have to prepare and design for engagement. I recommend before the Zoom meetings, send an agenda in advance, this gives your introverts time to process ideas, post questions prior so that people are ready to prepare and they had time to think in the meeting. Always start with clarifying, here's what success looks like at the end of the meeting.”

Despite the challenges that come with digital communication, she pointed out that there are advantages too.

“This is an opportunity to be more inclusive,” she said. “We can invite anyone into the video room. We can include anyone.”

As for the Zoom wave? Forget your awkwardness, and embrace it as a part of how we communicate during a pandemic.

“Get over it and empower yourself to use it,” Dhawan said. “I think that is my big mantra.”