Spring rolls, hot and sour soup, fried rice, and ginger chicken – for many Jewish families in Canada and the U.S., these are the some of the classic Chinese restaurant dishes they’ll share with friends and family on Christmas Day.

There’s a longstanding tradition of Jewish families in Canada and the U.S. going out to eat Chinese food on Dec. 25.

The custom dates back to at least 1935, when the New York Times mentioned a Chinese restaurant owner bringing chow mein to a New Jersey Jewish children’s home on Christmas Day.

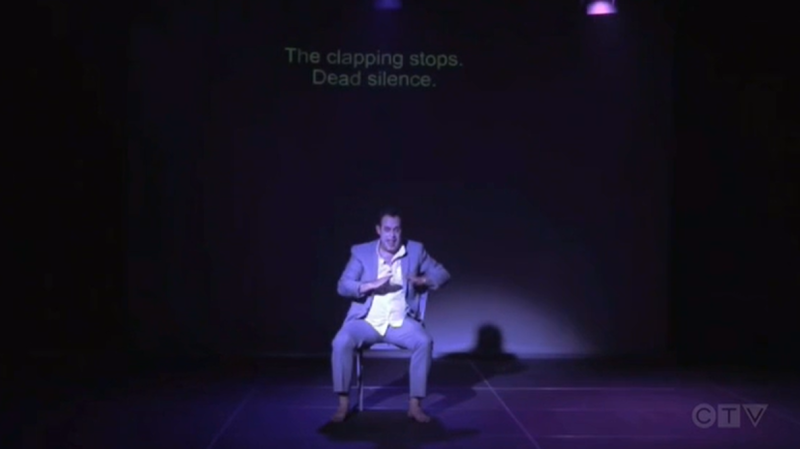

The custom is now so well-known it’s been studied, parodied, and was once even referenced by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan during her 2010 nomination hearing.

Here’s a closer look at how the tradition started.

A matter of convenience

When Jewish and Chinese immigrants first started arriving in Canada and the U.S., they didn’t observe Dec. 25 as a holiday.

This meant Jewish families were typically free on the Christmas Day holiday, and Chinese restaurants were open too, says historian and food writer Lara Rabinovitch.

“It’s not a new trend, of Jewish immigrants and later their children, and then their children’s children eating at Chinese restaurants on Christmas Day,” Rabinovitch told CTVNews.ca in a FaceTime interview from Toronto.

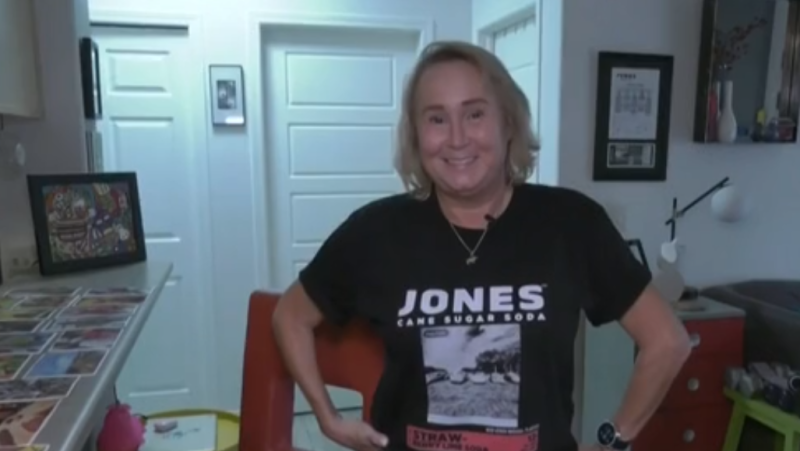

Canadian chef and renowned cookbook author Rose Reisman remembers her parents taking her to eat in Toronto’s Chinatown on Sundays and on major Christian holidays.

“When these Christian holidays came, stores weren’t open, and (my parents) didn’t want to cook at home. So Chinese food restaurants were the only ones open at this time, and that became the culture,” she said.

Parallel immigration patterns

A similar immigration history of the Jewish and Chinese communities in North America also likely had a hand in forming this custom, says Rabinovitch.

Large waves of Jewish and Chinese immigrants started arriving in Canada and the U.S. during the 19th and early 20th centuries, with many settling in large urban centres, such as New York City and Toronto.

As new immigrants in these growing cities, they often ended up living in close proximity, says Rabinovitch.

Reisman remembers her parents telling her about the discrimination they faced when they first came to Canada from Eastern Europe, much of it aggressive in nature.

“When they came to this country they were foreigners. There was a Christian philosophy and mentality in this country, and they didn’t feel like they fit in,” Reisman said.

“Apparently, that was very common with the Chinese as well.”

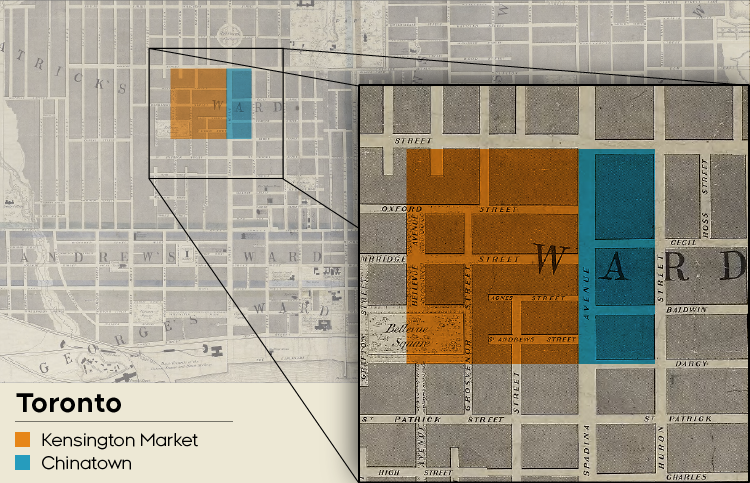

(Map: Public Domain, Jesse Tahirali)

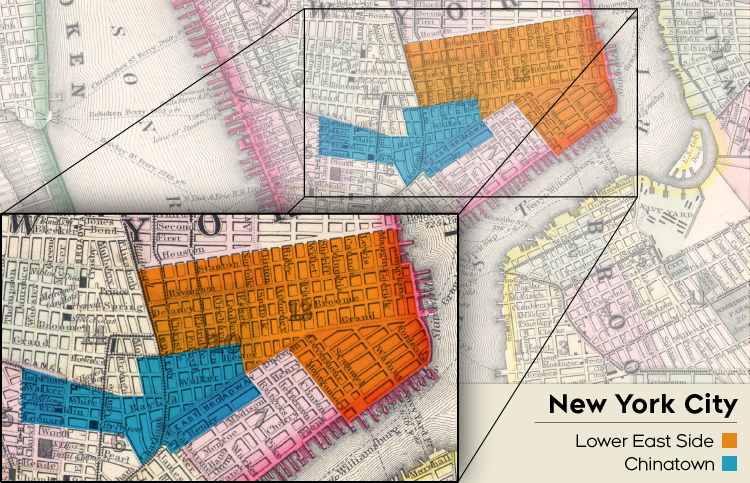

(Map: Public Domain, Jesse Tahirali)

Rabinovitch says this physical closeness ultimately led to these two immigrant groups interacting with each other.

“Where Chinese restaurants developed and thrived, Jewish communities also developed and thrived,” she said. “So there was an almost natural fusion, you could say, of the two groups in a social kind of way.”

Indeed, notes Rabinovitch, eating at a Chinese restaurant might have been one of the first ways Jewish immigrants had close contact with Chinese immigrants.

“These immigrant groups were really living and breathing on top of each other in places like downtown Toronto, where present-day Spadina (Avenue) and Kensington Market are,” she said.

“These were also neighbourhoods where some of the earliest Chinese restaurants were, and where early factories where Jewish workers worked as well. So this is maybe where the tradition was born.”

In New York City in the early 20th century, Jewish and Chinese immigrants also lived in neighbouring communities, mostly inhabiting Manhattan's Lower East Side and Chinatown.

New York City's Chinatown, circa 1930. (Getty Images)

Similar but different

But not everyone agrees with that theory, Rabinovitch says.

“There’s an opposite end to this theory, that maybe it’s that opposites attract,” she said. “So maybe it’s not so much the similarities that bring Chinese and Jews together, but maybe it’s the opposites.”

A tension between the familiar and the “exotic” also underlies the respective cuisines, Rabinovitch argues.

There are some common threads in Ashkenazi Jewish and Chinese food, for example, including their common use of garlic and onions for seasoning. As well, Chinese food typically lacks dairy, and Jews who keep kosher must separate meat and dairy ingredients, says Rabinovitch.

There are also dishes that loosely resemble each other, including dumplings (wontons and kreplach) and root pancakes (turnip and latkes).

But the cuisines are also markedly different. For example, Chinese food tends to include a lot of pork and shellfish – both of which are prohibited for Jews who keep kosher.

And yet, for many Jewish-Canadians, a Chinese restaurant was one of the few places dietary rules would be relaxed, says Toronto-based chef and restaurateur Anthony Rose.

“We grew up in a kosher house, but once you were at a Chinese restaurant that all just went right out the window,” he recalls. “All of a sudden you are eating BBQ pork slices, pork fried rice … it was like there were no rules all of a sudden.”

Reisman says her parents might have overlooked the restrictions in these cases because pork and shellfish is often disguised in Chinese cooking– chopped up in a sauce, for example, or concealed in a dumpling.

“As long as it was buried away in rice, you could pretend it was chicken or beef, and that was OK,” she said. “I mean, the only thing you couldn’t do in a Chinese-food restaurant was have the (roast) pig presented with the apple in its mouth.”

Growing up, Reisman recalls marvelling at the bold flavours found in Chinese food.

“The sweet and sour, the spices… my mother would not approve of me saying this, but I always found it way more exciting than Jewish food.”

'A party'

This culinary custom has become so common that it wasn’t unusual to run into other Jewish families you knew at your favourite Chinese restaurant, says Rose.

“You would walk in there, and it was like a bar mitzvah. It was like a Jewish wedding,” he says of the now-closed Lichee Garden in Toronto. “There was tons of people everywhere and you knew every single one of them.

“It was not only friends, but family. I could walk in there and my Uncle Meyer and my Auntie Bonnie would be at the table next to us, it was very funny.”

Rabinovitch also recalls seeing familiar faces at her favourite spot on Christmas Day, sharing platters of food amid the sounds of clicking chopsticks and rounds of tea.

“Everybody kind of knows each other in one way or another,” she said, describing the festive atmosphere. “A party… oh yeah, a party.”