Vegan options at McDonald’s could have been a Saturday Night Live sketch ten years ago. But today, even non-vegans expect vegan options on restaurant menus.

This is hardly a surprise, with a recent Dalhousie University study estimating that vegetarians and vegans comprise nearly 10 per cent of the population, or 2.3 million Canadians.

The Vegan Society defines veganism as seeking to eliminate “all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose.”

This means not eating meat; wearing clothing made from animals, such as leather; or using items made with animal by-products, such as some glues or beers.

While tofu entrees or veggie burgers are relatively easy to stomach, insects aren’t for everyone. But they should be on menus to prevent more sentient animals from dying, according to some non-meat eaters who don’t fit the definition of a vegan.

For them, it all boils down to sentience — which animals actually perceive or feel pain.

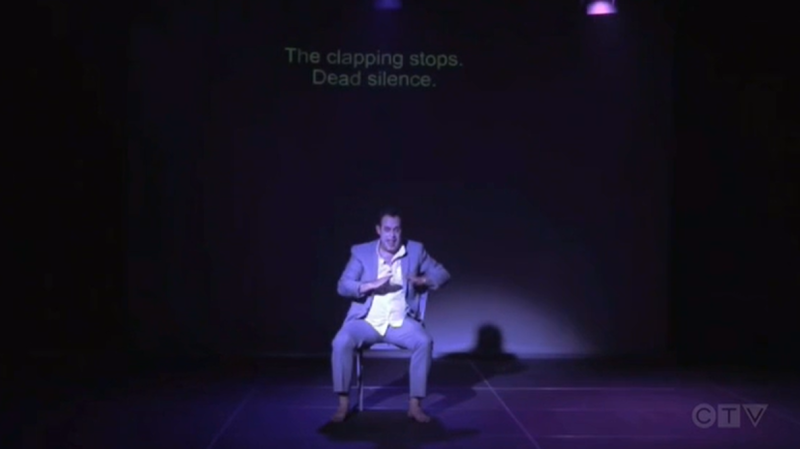

The Vegan Mac Daddy, as served at Doomie's Toronto, is seen in an undated handout photo. (THE CANADIAN PRESS / HO - Doomie's Toronto, Eva Lampert)

Veganism still accepts animal deaths

When people choose to go vegan they typically cite environmental concerns, personal health reasons and, perhaps most importantly, the desire to reduce harm to animals.

But even if everyone on Earth went vegan, plenty of animals would still be killed.

Even small-scale, plant-based agriculture kills “not just innumerable insects but also field mice, rabbits and rodents, deer and anything that competes with that crop,” former vegan advocate James McWilliams told CTVNews.ca over the phone.

Every year, pesticides and neonicotinoids used for plant agriculture kill thousands of insects and bees respectively. Combines, threshers and harvesters rip apart a wide range of animals, each year. The bottom line is that so-called “humane” foods will unintentionally kill or harm sentinent life. But that exact number of animals may be harder to pin down.

“I’m certainly not going to make the argument that we need to stop eating plants, that’s just absurd,” McWilliams said.

However, he believes there’s something else ethical eaters should do: supplement a plant-based diet with bugs and oysters, which some evidence suggests they have no perception of pain.

“An ethical vegan who’s only committed to eating plants might very well be contributing to more animal suffering than an individual who eats insects,” he said.

Several combine harvesters work a wheat field, approximately 20-kilometres south of Lethbridge, Alb. on Monday, Aug. 13, 2001. (Adrian Wyld / THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Could eating fewer plants, more bugs lead to fewer animals dying?

McWilliams now considers himself “vegan-ish” because despite not eating chicken, pork or beef and being conscious of where his food is coming from, he supplements a plant diet with insects “primarily for ethical reasons.”

Most creatures, including wasps and fruit flies, have nociceptors which detect stimuli, including potentially painful ones. But there is an ongoing debate within the scientific community questioning whether creatures, including insects, can even feel pain or consciously experience it.

One of the entomologists trying to determine whether insect suffer is Hans Smid of Wageningen University in the Netherlands, who studies parasitic wasps which are highly intelligent. But he’s “absolutely convinced that insects do not feel pain.”

He said insects don’t exhibit pain-related behaviours and, as such, don’t suffer.

McWilliams echoes some experts’ rationalizations that insects’ lifespans are so short that it would be a “waste of evolutionary energy” to develop systems like pain instead of advantages like faster reproduction.

These were the eureka moments for the former vegan to choose the intentional death of animals who feel no pain to reduce the unintentional, sentient animal deaths from solely plant-based diets. “I basically talked myself out of veganism.”

“If you want to look at it on strictly utilitarian terms, the (vegan) argument just doesn’t hold up,” McWilliams said, adding he doesn’t fit the bill of what it means to be a vegan anymore.

Raychel Santo, a senior research program coordinator at Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future in Baltimore refrains from eating bugs but said ethical eaters need to grapple with the discussion.

We need to stop thinking bugs are gross

But Raychel Santo, a senior research program coordinator at Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future in Baltimore — who is a vegan herself — says ethical eaters need to wrestle with the ramifications of considering bug diets as vegan.

She refrains from eating meat for several reasons: greenhouse gas emissions produced from grazing cattle, the resource-intensive methods to raise them and the pain animals feel in cramped cages before some of them are slaughtered.

But none of these issues apply to insects.

She and her graduate class from the food, space and society program at Cardiff University tried several insect dishes at the Grub Restaurant in Wales, U.K, where the menu included “bug bhaji” (an Indian fritter dish made with mealworms), bug burgers and entrees made with cricket flour.

Sarah Beynon, the entomologist who runs the restaurant, freezes the bugs before cooking with them but acknowledges the debate to kill them by shredding them, Santo wrote in blog post.

Santo says conscious eaters should care less about adhering to vegan orthodoxy and suggests insect-diets could be “one part of our transition to a more sustainable food system.”

Oysters for sale are seen in this undated file photo. (Bayne Stanley / THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Some say oysters, mussels are vegan, too

Part of that ethical wrestling goes well beyond insects.

Diana Fleischman, an evolutionary psychologist and senior lecturer at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., has been examining animal sentience for years.

She describes herself as a conscious eater but an ex-vegan because she doesn’t fit into the traditional definition.

“I specify that bivalves, particularly oysters and mussels … do not have what I think is the neural architecture to suffer,” she told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview.

But in a blog post, Fleischman said that although bivalves respond to noxious stimuli, they lack the neural hardware or response consistent with an ability to feel pain.

She compared bivalves to a “disembodied finger” without a brain.

Fleischman said unlike other animal farming, oyster and mussel farms don’t kill other sentient life, which can be a byproduct to fish-based diets. She cites evidence showing dismal number of species caught in fish or shrimp nets and promptly discarded.

She also said that oysters contain nutrients like B12, omega-3 fatty acids and zinc, which could be difficult to source in a vegan diet.

Fleischman explains that scientists categorize forms of life primarily based on evolution and tracing a common ancestor between species. But she argues that life should be re-categorized with sentience in mind.

Some philosophers and ethologists are already delving into the debate by trying categorize species based on if whether they’re sentient creatures (who are self-aware or not), inanimate objects and insentient organisms.

“If someone wants to maintain the spirit of veganism, then it makes sense to eat bivalves,” Fleischman said.

Farming oysters improves the lives of other ocean creatures

McWilliams wholeheartedly agrees, and also insists that the argument vegans should eat oysters is even stronger than the case for eating insects.

He cites studies showing how oyster farms can help to improve ocean water quality which benefits other animals, which would bolster another pillar of veganism: caring for the environment.

“I think it’s not just permissible to eat oysters but they (vegans) would have an obligation to eat oysters,” McWilliams asserts.

Fleischman said judging how much animal suffering goes into all of our meals should be crucial for any eater.

She referenced charts which lay out the amount of direct animal suffering that goes into production of different types of meats and dairy products.

These were compiled by Brian Tomasik who runs the website “Essays on Reducing Suffering,” which examines ethical issues surrounding conscious eating.

This “utilitarian calculation” appealed to her because she said it “seems like a way of putting ethics into practice.”

Vegan protesters gather outside of the Antler restaurant in Toronto on Saturday, March 31, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chris Donovan

Labels like vegans or meat-eaters will become meaningless

This is why Fleischman doesn’t buy the argument that vegetarians, who still eat eggs and milk, are ethical eaters because of potentially troubling situations involved in chicken and dairy cow farming. i

“I would sooner eat a piece of steak than I would eat an egg,” she said, referencing an analysis showing how “one egg has more deaths per calorie and a lot more suffering involved.”

But in the coming years, Fleischman said the categories of eaters, including herself, are bound to change even more.

Future discussions could include whether it’s ethical to eat “clean meat,” or meat grown from animal cells in laboratories, she said.

In the near future, these “clean-meat-itarians” will be “indistinguishable from people who are vegan,” she said.

McWilliams said vegans are going to face tough choices but that it’s hard to say how the movement will adapt — if at all.

“If you concede the argument, you essentially have to do away with veganism because it has defined itself quite radically as not eating (or exploiting) animals,” he said, adding that it could undermine the movement.

“I think there are other ways to eat ethically … you might need to come up with a new name,” said McWilliams, who now more aligns with those on “periphery of the food system.”

These outsiders could include people who eat roadkill and “freegans” who dumpster dive, who both argue that throwing away food is wasteful to the environment if it can still be eaten safely.

And if animals have already suffered but their meat and byproducts won’t be eaten, McWilliams said vegans can’t ignore the waste to the environment.

Fleischman said in the coming years, more conversations will involve people asking “how do I decrease my suffering footprint as much as possible?” rather than just asking: “Is this vegan?”