One of Canada’s most notable music producers is opening up about his struggle with depression and his son’s death, in hopes of shattering perceptions of shame often associated with mental health.

Bob Ezrin has worked with some of the world’s biggest rock stars, including Pink Floyd, Alice Cooper, Peter Gabriel and KISS. He was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 2004 for his storied career and his work to support Canadian music education.

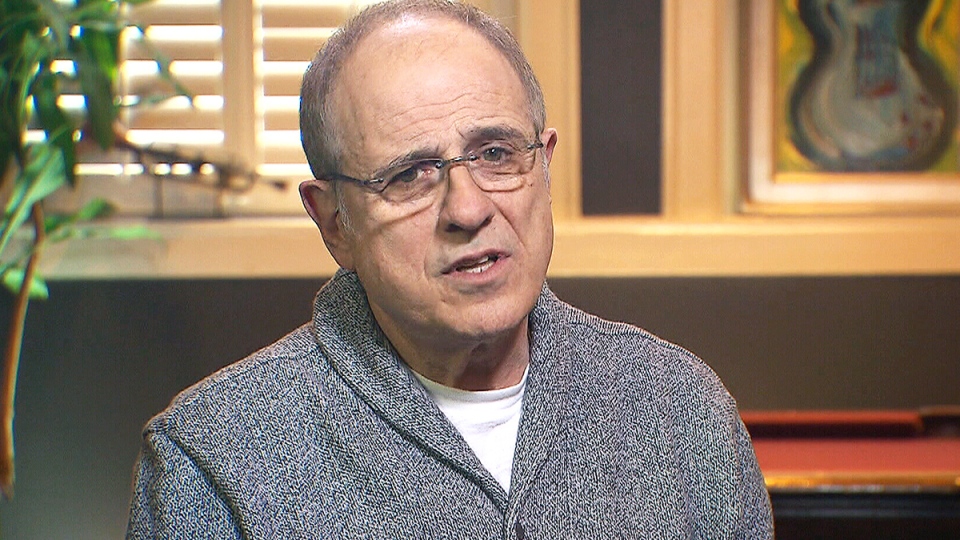

But in an interview from his Nashville studio, Ezrin says he struggled with depression early in his career, and he often self-medicated with drugs.

“Which really didn’t help very much in fact, exacerbated things,” he told CTV News.

Ezrin eventually reached a point where he says he “finally surrendered” to proper medical treatment. He lived in Toronto and found help at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Decades later, he remains on medication.

“It’s been decades since I’ve had any major episode. Every once in a while there’s an echo, a faint reminder of those feelings, so I know that’s still there,” he said.

Legendary rock star Alice Cooper, who was in a recording studio with Ezrin working on a new album, joined in the discussion about mental health. The two music icons have been friends for some 47 years.

“I really believe everybody has a certain amount of mental disability. I think we are born with certain phobias, certain things we are afraid to talk about,” Cooper said.

The veteran shock rocker recalled his early years in music, a time he said he followed in the reckless footsteps of his fellow musicians.

“I was in generation where we looked at our big brothers. My big brothers were Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. And they were already doing every drug in the world and drinking every day and living this lifestyle that was very appealing, especially for a Christian kid. And so I fell right into it,” he said.

Cooper said he drank every day and, after a while, began taking drugs. It took him years to realize that he had a problem.

“I didn't realize that I was an alcoholic until I realized that the alcohol was not for fun anymore. It was medicine.”

He turned things around by going into treatment and renewing his childhood roots in Christianity.

But mental health issues seep into his music. Cooper wrote “Hey Stoopid,” a song about teen suicide, which includes the lyrics: “No doubt you’re stressin’ out/That ain’t what rock n’ roll’s about/Get off that one way trip down lonely street.”

“That song in particular, I’ve gotten so many emails: ‘That song saved my life,’” he said.

On the eve of Bell Let’s Talk Day, Ezrin says he wants to urge people struggling with mental health not to feel ashamed. In fact, according to the Canadian Mental Health Institute, about 20 per cent of Canadians will directly experience a mental illness in their lifetime.

“Some people have organ issues, muscle issues, back issues … I have a brain issue and I treated it and I feel much, much better.”

Ezrin said an even more painful experience with mental health was watching his son David grapple with obsessive compulsive disorder and schizophrenia. Like his father, David was a music composer and songwriter.

But because of his condition, David sometimes refused to acknowledge that he needed help and would sometimes stop taking his medication.

“So that makes it very difficult to treat,” Ezrin said. “His therapist actually said to me, ‘You’re going to get a phone call. He’s either going to hurt himself or someone else.’”

Ezrin found out that David died of suicide in 2008 when he and his ex-wife didn’t hear from their son on his birthday.

“I did the best that I knew how to do during his life, in spite of some really abusive behavior on his part. I stuck with him and supported him. And yet it was like watching a slow-motion train wreck,” he said.

Ezrin said he hopes that by sharing his story, he can encourage other Canadians to share their own experiences to help dispel stigma.

“My objective with this is just to encourage people not to feel that this some kind of weird thing that’s going on inside of them or something of which they should be ashamed. You know, it’s not our fault.”

With files from CTV National News medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip