Scientists believe they’ve discovered a biomarker for depression, a discovery that could lead to a blood test capable of determining the effectiveness of various antidepressant medications, potentially as early as one week into treatment.

In a small proof-of-concept study, researchers took blood samples from 41 patients with major depressive disorder and compared them to a control group of 44 individuals without depression, in order to isolate a biomarker that can track the disorder.

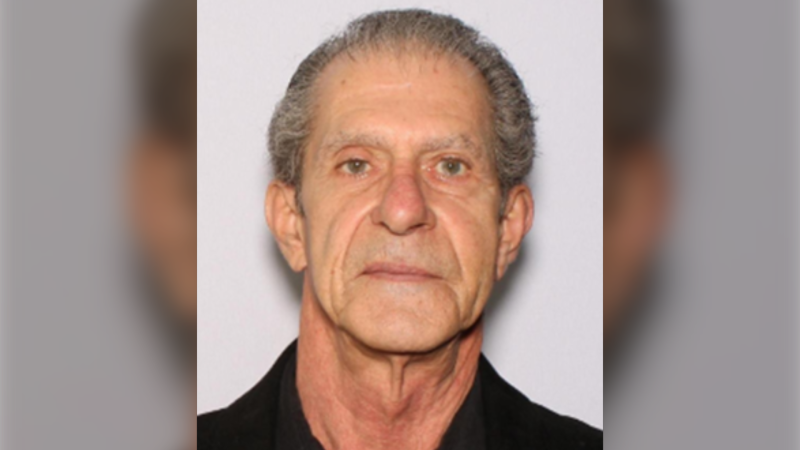

“What we have developed is a test that can not only indicate the presence of depression but it can also indicate therapeutic response with a single biomarker, and that is something that has not existed to date,” Mark Rasenick, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago and lead of the study, said in a press release.

Previous studies have found that those with depression also have decreased adenylyl cyclase, which is an enzyme that is present in almost all cells and is part of the complicated process of signalling neurotransmitters such as serotonin and epinephrine.

“When you are depressed, adenylyl cyclase is low,” Rasenick said. "The reason adenylyl cyclase is attenuated is that the intermediary protein that allows the neurotransmitter to make the adenylyl cyclase, Gs alpha, is stuck in a cholesterol-rich matrix of the membrane — a lipid raft – where they don’t work very well.”

In the new study published in the January edition of the journal Molecular Psychiatry, researchers identified a cellular biomarker — the shift of the protein Gs alpha from lipid rafts — that signals depression. This biomarker can be found through a blood test, they say.

Researchers got their data from a six-week trial that looked at patients experiencing an acute major depressive episode who consented to be part of the study. Patients were found for the study between September 2013 and May 2016, and they were compared to a control group of individuals who had no history of depression.

In the study, blood samples were taken from patients in at least two instances separated by a week. At the second visit, patients who wanted to try undergoing medication to treat their depression were prescribed an anti-depressant after consultation with a study psychiatrist.

These patients had follow-ups six weeks later to assess their symptoms and draw more blood.

Researchers focused specifically on the platelets in the blood, where they found the biomarker.

The study found that patients with depression had “significantly lower […] activation of adenyl cyclase activity in platelet samples than healthy controls,” but they also found that those who responded well to anti-depressant treatment had a “marked increase in […] adenylyl cyclase” at the six-week check-in compared to those who did not respond to the anti-depressant treatment they were taking.

This supported previous research that found that when patients taking anti-depressants were reporting improvement of their depressive symptoms, the Gs alpha protein was found to have moved out of the lipid raft. But patients on anti-depressants who reported no improvements in their symptoms had the Gs alpha still trapped in the lipid raft.

Anti-depression medication can be life changing for some, but for others it can take months to see impacts, or require going through the exhausting process of testing out numerous types to find one that works.

If a blood test could show whether the Gs alpha protein was shifting out of the lipid raft as an indicator of the medication’s success, it could help streamline the process of finding a medication that works for individual patients, something that could be hugely important considering how many anti-depressant medications are on the market.

“Because platelets turn over in one week, you would see a change in people who were going to get better,” Rasenick said. “You’d be able to see the biomarker that should presage successful treatment.”

It could also potentially identify which patients will benefit from medication to treat their depression, and which patients need other avenues to relieve their symptoms.

Rasenick is hoping to develop a screening test with his company Pax Neuroscience in the future if further research is successful.

“About 30 per cent of people don’t get better — their depression doesn’t resolve. Perhaps, failure begets failure and both doctors and patients make the assumption that nothing is going to work,” Rasenick said. “Most depression is diagnosed in primary care doctors’ offices where they don’t have sophisticated screening. With this test, a doctor could say, ‘Gee, they look like they are depressed, but their blood doesn’t tell us they are. So, maybe we need to re-examine this.’”

Researchers noted in the study that they lacked a placebo group, so it hasn’t been fully established if the anti-depressants did cause an increase in adenylyl cyclase or not. The study was also limited by its small scope, and researchers are hoping to perform larger studies in the future, including ones which could compare different types of anti-depressants.