Most women in the early stages of one of the most common forms of breast cancer can safely skip chemotherapy if genetic tests reveal their risk for cancer recurrence is low, results from a new study reveal.

“We were able to identify that about 70 per cent of patients who we would normally recommend chemotherapy to don’t benefit from it, don’t need it,” the study’s lead author, Dr. Joseph Sparano, said in an interview.

The findings could mean that thousands of Canadian women might not have to endure the nausea, hair loss, and other side effects of the chemotherapy medications that can keep cancer at bay but that carry plenty of risks of their own.

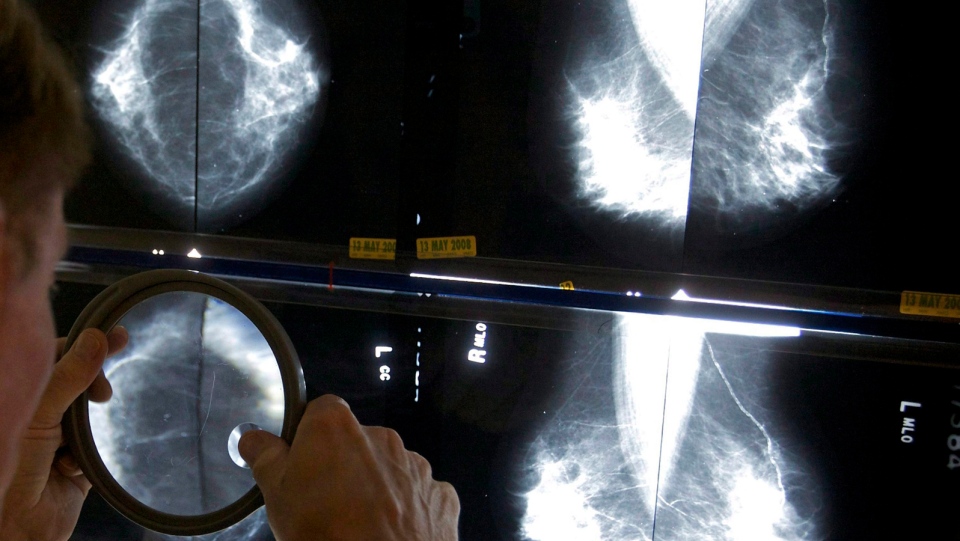

The study applies only to women with breast cancers that are “hormone receptor-positive” – meaning they are fuelled by estrogen and progesterone -- and “HER2-negative,” and that have not spread to lymph nodes under the armpits.

The usual treatment for such patients is surgery to remove the tumour, followed by several years of hormone-blocking medications, such as tamoxifen. Many women are also urged to undergo chemotherapy to help kill off any cancer cells that might have migrated from the tumour.

But this study -- the largest breast cancer treatment study ever -- finds that most of these women do not actually need chemo.

The study recruited more than 10,000 breast cancer patients and had them undergo a genetic test called Oncotype DX. For the test, a sample of the tumour was removed and tested for activity of 21 genes that are known to be involved in cell growth and that respond to hormone therapy. Each woman’s tumour was then assigned a score.

About 17 per cent of the women had scores that showed they were at high risk of recurrence so they were advised to take chemo. Another 16 per cent had very low risk scores and were told they could skip chemo. This study focused on the rest of the women who were in the intermediate risk range.

These mid-range women were randomly assigned to either receive hormone therapy alone, or hormone therapy and chemotherapy. They were then monitored for an average of 7.5 years to see how many of them died or had their cancer recur.

For most of the women, skipping chemo made no difference: a full 94 per cent of both groups were still alive after nine years, and about 84 per cent were alive without any signs of cancer.

The researchers did find that some patients who were diagnosed at age 50 or younger and whose risk scores were on the higher end of the mid-range did benefit from chemotherapy.

They say their findings suggest that chemotherapy can be skipped in most women older than 50 who have this form of breast cancer and who have mid-range and low risk scores.

The study’s lead author, Dr. Joseph Sparano, the associate director for clinical research at the Albert Einstein Cancer Center in New York, says patients with early stage breast cancer should consider this kind of testing.

“Any woman with early-stage breast cancer 75 years or younger should have the test and discuss the results of [this study] with her doctor to guide her decision regarding chemotherapy after surgery to prevent recurrence,” Dr. Sparano said in a statement.

Dr. Harold Burstein, an expert with the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) says the finding provide reassurance to doctors and patients that genetic tests can make treatment decisions easier.

“Practically speaking, this means that thousands of women will be able to avoid chemotherapy, with all of its side effects, while still achieving excellent long-term outcomes,” he said in a statement.

“Being able to say to a patient that truly there’s no benefit for chemotherapy in your case, based on a test of your cancer, that’s a very powerful intervention,” Burstein added in an interview.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute in the U.S., and the results were presented Sunday at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference in Chicago and were to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Several of the study authors consult for the company that makes the gene test or for breast cancer drugmakers.

In Canada, where one in eight women will develop breast cancer, many doctors are hoping to use the study’s findings to change how they treat the disease.

“It means we can better use the treatments… so that we can achieve our ultimate goal,” Dr. David Cescon of Toronto’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre told CTV News. “Which is delivering the most effective and least toxic therapy to patients.”

With files from CTV National News Vancouver Bureau Chief Melanie Nagy and The Associated Press