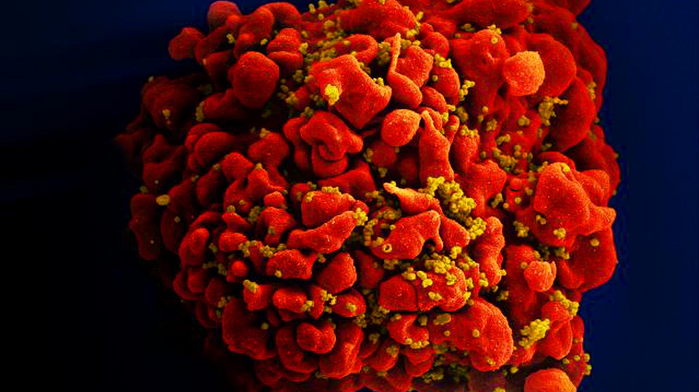

Living with HIV may have an immediate effect on how your body ages, according to new research which showed that cellular aging was sped up in male patients within two to three years of infection.

Researchers with University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) looked at blood samples from more than 200 men to compare those infected with HIV to a control group who did not have HIV, and scored them on five different measures of aging.

The study, published Thursday in the journal iScience, found that those living with HIV showed aging that was 2-5 years ahead of non-infected counterparts within three years of infection.

“Our work demonstrates that even in the early months and years of living with HIV, the virus has already set into motion an accelerated aging process at the DNA level,” Elizabeth Crabb Breen, professor emerita at UCLA’s Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology and lead author of the study, said in a press release. “This emphasizes the critical importance of early HIV diagnosis and an awareness of aging-related problems, as well as the value of preventing HIV infection in the first place.”

HIV is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system, leaving the patient vulnerable to serious illness from even mild diseases or medical issues. In advanced stages, it can lead to AIDS, in which the immune system is severely damaged. There is no cure for HIV, but those who are living with HIV can manage it safely and prevent themselves from passing it on with current treatments.

As of data from 2018, around 62,000 people in Canada are living with HIV.

Scientists have previously theorized that HIV and the antiretroviral therapies that keep the infection under control could contribute to this accelerated aging, but this is one of the first studies to directly compare infected and non-infected people to look at this question, according to the release.

Researchers used data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, an ongoing study that began in 1984.

They looked at blood samples taken from 102 before they became infected with HIV and then two to thee years after infection, and matched these patients to samples taken from 102 men of the same age over the same time period.

But how can blood show your aging? By examining the question on a subcellular level.

Researchers used the lens of epigenetics, which is the study of how your environment and behaviours change how your genes work — for instance, whether your body will follow the genetic instructions to create a specific protein, or whether epigenetic changes will have turned that gene “off”.

Some epigenetic changes are reversible, and some are progressive, such as how aging affects our gene expression.

By looking at how HIV affects DNA methylation, a type of epigenetic change which turns genes off and prevents them from reading the instructions to create certain proteins, researchers measured different indicators of aging within the samples.

Four of these are known as “epigenetic clocks”, and involve comparing different levels of methylation, lymophocytes, or other indicators to an established norm.

The last of the five aging indicators was to look at the length of telomeres, which are the ends of chromosomes that become shorter with each time that cells divide, until they become so short that cell division is no longer possible — one of the many clear measures of how aged a body is, as our bodies are steadily aging from the moment that we have more dying cells than replicating cells within us.

What researchers found was that in the patients with HIV, there was significant age acceleration across all five the aging measurements just before infection and ending two to three years after.

“This clearly demonstrates an early and substantial impact of HIV infection on the epigenetic aging process that begins in the first months and years of living with HIV,” the study stated.

“Becoming infected and living with HIV for only three years or less is already associated with approximately 20 per cent increased risk for a shortened lifespan."

There was no accelerated aging seen in the non-infected control group in that time period.

The associations persisted even after researchers controlled for other factors in the men’s lives that could be contributing to accelerated aging.

“Our access to rare, well-characterized samples allowed us to design this study in a way that leaves little doubt about the role of HIV in eliciting biological signatures of early aging,” Beth Jamieson, a professor in the division of hematology and oncology at the Geffen School and senior author, said in the release. “Our long-term goal is to determine whether we can use any of these signatures to predict whether an individual is at increased risk for specific aging-related disease outcomes, thus exposing new targets for intervention therapeutics.”

The researchers noted that the study was limited by its small sample size, as well as it consisting exclusively of men and primarily of white men, meaning that broader studies need to be done to be sure if these results are applicable across the board.

Although this is the largest study of its type, it only followed the patients up to three years after infection.

Researchers say more research needs to be done to ascertain if this accelerated aging is sustained throughout the life of a person with HIV, and if it predicts longer term clinical outcomes.