TORONTO -- While most people have heard of microplastics and how they’re polluting the environment, a long-time environmentalist wants them to also know that these tiny bits of plastics are most likely entering their bodies too after he conducted an unusual experiment on himself.

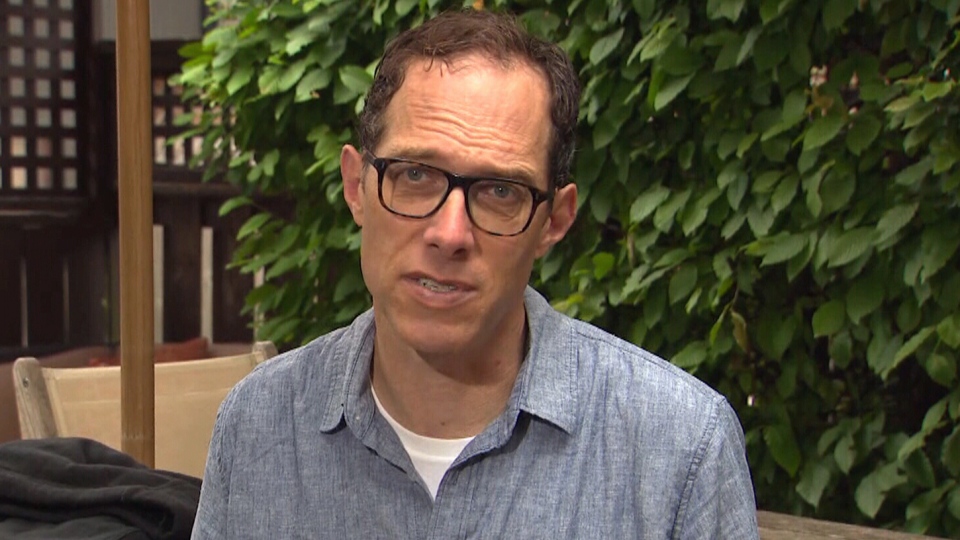

Rick Smith, the executive director of the Broadbent Institute and co-author of “Slow Death by Rubber Duck,” said he was interested in finding out if microplastics were seeping into human bodies from the products we use, the clothing we wear, and the food we consume.

There have been numerous studies showing evidence of microplastics winding up in the environment, particularly in oceans.

The small plastics fragments can enter the environment in numerous ways, including sloughing off of vehicles’ tires and washing into streams. The fragments also detach from clothing with plastics in the fabric, such as polyester and nylon, during the machine-washing cycle. And then there’s the eventual breakdown of single-use plastics, such as straws, that are thrown out.

Smith said that while the discovery of microplastics in the environment is being heavily studied, he’s only aware of one study with a rather small sample size out of Europe and Asia that has examined the existence of microplastics in humans.

In an effort to learn more about this possibility, Smith teamed up with the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York to find evidence of microplastics in humans using his own body as the test subject.

“The study that I've done is the first of its kind. So for good or ill, I’m the first person who can say that, yes, here in North America, North Americans have these microplastic fibres and fragments in our bodies,” he told CTV News.

Over the course of six days in January, Smith sent daily samples of his stool to researchers at the Rochester Institute of Technology to test for microplastics.

For the first two days of the experiment, Smith lived and ate as he normally would. Over the next four days, however, he did things that he thought would increase his intake of microplastics.

Smith ate food that had been shrink-wrapped in plastic, he drank only bottled water, he heated his food in plastic containers in the microwave, and he prepared his coffee in a machine made with plastic parts.

The environmentalist also took it a step further and wore clothing laced with plastic, such as a fuzzy fleece he received for Christmas, over those four days.

Not only did the researchers find microplastics in his stool every day of the experiment, they also detected higher levels of fragments in the later days of the study when Smith was actively trying to expose himself to more plastic.

“We found substantially more microplastics in the samples and were able to identify them,” said Nathan Eddingsaas, an associate professor in chemistry and materials Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

However, he noted that “a lot more” research needs to be done on the topic, including looking at exactly how microplastics affect human health.

While Eddingsaas said he wasn’t surprised by the results of the experiment, Smith was of a different opinion.

“These results are shocking, they’re surprising,” he said. “The human health implications are staggering. If there’s microplastics in me, if my microplastic levels actually increase or decrease depending on how much plastic I’m using in my daily life, what it means is that we’ve all got microplastics in us.”

The plastic industry says research hasn’t shown significant human health impacts from microplastics.

Smith, on the other hand, said the doctors and scientists he spoke to about his results are increasingly concerned about the potential health consequences of microplastics in the body.

“These tiny plastic particles are small enough that when we breathe them into our lungs, when we ingest them in our food and drink, they can actually pass through our gut lining into our bloodstream. They can be transported around our bodies to organs that clean our blood like our livers, they can get deposited in our brains,” he said.

Kieran Cox, a marine biology PhD candidate and Hakai Scholar at the University of Victoria, said that while Smith’s experiment is valuable on an anecdotal level, more studies are needed to understand the true toll microplastics could have on human bodies.

“The health implications are going to be very difficult to untangle, and it's going to be a multi-phase collaborative effort, and it's actually going to extend probably multiple years to try to figure this out,” he said.

“The short answer is we don't know. But the field is moving very quickly.”

The research on this topic may still be in its early stages, but Smith said he’s not taking any chances with his or his family’s health. He said they already try to reduce their use of plastic in their daily lives as much as possible by eating food from glass or metal containers and never drinking out of plastic water bottles.

“I think what we can deduce from my experiment is that using less plastics in your daily life is going to result in less microplastics in your body,” he said. “I mean it seems common sense, but it's nice to have that confirmed.”