Doctors are turning to a 100-year-old therapy that harnesses viruses to kill drug-resistant bacteria after the approach was recently used as a last-ditch effort to save a California man’s life.

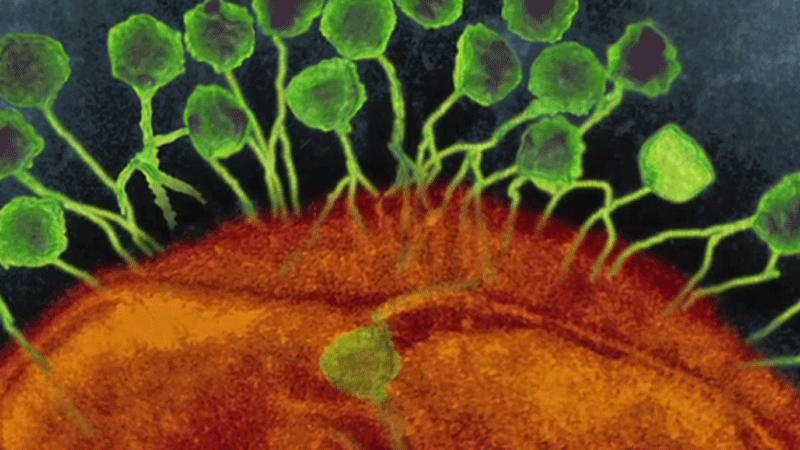

It’s called bacteriophage therapy, and it uses a unique cocktail of viruses to target and neutralize harmful bacteria in a patient’s body. In Greek, bacteriophage literally translates to “bacteria eater,” and the microscopic organisms are found in all corners of the planet.

It’s a method that 69-year-old psychiatry professor Tom Patterson credits with saving his life. He was in Egypt, on vacation in 2015, when he became infected by a severe strain of acinetobacter baumannii, a potentially deadly pathogen in his pancreas.

Wracked with intense pain and nausea, Patterson was airlifted home to California, where he received treatment at the Intensive Care Unit at Thornton Hospital in La Jolla.

That’s when doctors realized his infection wasn’t responding to medication.

“We were confronted with a man who was infected in multiple locations with an organism that was not sensitive to the antibiotics we had available and that we couldn’t drain adequately,” Dr. Robert Schooley, professor of medicine and chief of the division of infectious diseases at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, told CTV News.

Shortly thereafter, Patterson’s condition worsened. An internal drain localizing his infection slipped, causing bacteria to spill into his abdomen and bloodstream. Patterson fell into a coma for two months.

His wife, Steffanie Strathdee, recalled the harrowing time.

“I asked Tom, ‘Do you want to give up, or do you want to fight?’ He squeezed my hand and I knew he wanted to fight,” Strathdee said.

An unlikely solution

While doctors worked to stabilize Patterson’s condition, Strathdee, a Canadian who works as chief of the Division of Global Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine, began to research. A friend told her about phage therapy, a concept Strathdee learned about in a virology class at the University of Toronto.

Phage therapy was co-discovered in the early 1900s by French-Canadian microbiologist Felix d'Herelle and widely used at the turn of the 20th century. But it was quickly eclipsed by the discovery of antibiotics in the 1940s and eventually faded from Western medical research and application. However, it remained in therapeutic use in France and the Soviet Union.

With few options available and her husband’s condition worsening, Strathdee proposed the unusual solution to Schooley. They decided to give it a shot.

They received phage strains from from three sources: the Biological Defense Research Directorate of the NMRC, the Center for Phage Technology at Texas A&M University, and San Diego-based biotech company AmpliPhi.

The medical team obtained emergency approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to try the experimental treatment, which must be tailored to suit an individual patient’s case. For Patterson, the phage was administered intravenously and through catheters into his abdomen.

Within 48 hours of receiving the phage therapy, Patterson woke up from the coma.

“We began to see his blood pressure stabilize, his white [blood cell] count begin to come down, and it was very clear that he was having a clinical response to the bacteria phage,” Schooley said.

Three months after receiving the phage therapy, there was no evidence of the harmful bacteria in Patterson’s body. By the fifth month, he was sent home from hospital.

“I’m going to enjoy the rest of my life enormously,” Patterson said.

Phage therapy ‘not simple’

The World Health Organization estimates that antimicrobial resistance will kill at least 50 million people per year by 2050. Researchers hope Patterson’s remarkable recovery story could spark renewed interest for mainstream medicine to explore phage therapy as a treatment against drug-resistant bacteria.

“We’re going to need an additional alternative method of treating deadly bacteria, and so I see phage therapy as a front-runner for that alternate medicine,” said Jon Dennis, a microbiologist with the University of Alberta.

Dennis said Patterson’s case was extraordinary because it was the first time in North America that modern science paid attention to phage therapy as a viable treatment.

“There has been difficulty getting funding to do basic phage therapy research. The problem lies in that a lot of the phage therapy data that we have is historical, it’s anecdotal and it hasn’t been performed in the modern era,” he said.

But phage therapy is hardly a one-size-fits-all solution. Doctors need to create a unique combination of different types of bacteriophage for a patient’s particular case.

“They’re not simple to use,” Schooley said. “They seem to be relatively safe to give, but they’re going to be difficult to develop from both the research perspective, and also from the regulatory perspective, because each patient’s phage cocktail is a different cocktail.”

Despite the challenges, doctors are optimistic that the century-old method could be one way to fight the growing global threat of antibiotic resistance.

Meanwhile, Felix d'Herelle’s legacy lives on. At Laval University in Quebec, a reference centre where scientists can search and order phages has been named in his honour. This year also marks the 100th year since d'Herelle’s discovery, and the Paris-based Institut Pasteur celebrated the anniversary with a presentation of Patterson's case.

With a report by CTV News medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip