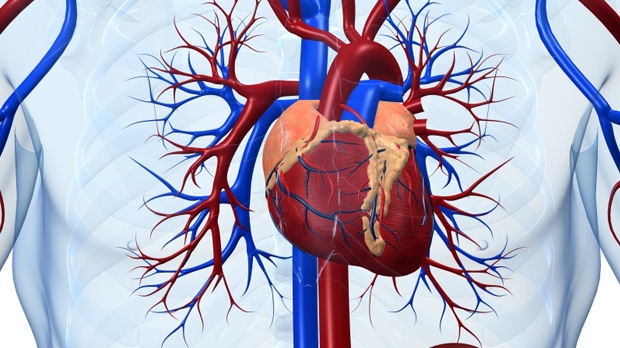

TORONTO -- People who are at high risk for heart disease and who have been treated in an emergency room for chest pains do better over the long-term if they see a doctor within 30 days of being released from hospital, a new study suggests.

In particular the study found that people who saw a cardiologist were more likely to be alive a year later than people who saw a family physician or didn't get any medical followup after an episode in which they were treated in hospital for chest pain.

"It does look like the cardiology group did more testing, did more treatment and then they had better care. But I think in their own environment, primary care physicians also did better than no physicians," said senior author Dr. Dennis Ko, a scientist with Toronto's Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

The study was published Monday in Circulation, a journal of the American Heart Association.

Ko said little is known about what happens long-term to people who go to emergency departments for chest pain and are cared for but don't need to be admitted to hospital.

Though they are urged to see a doctor for followup testing and treatment, there's currently no way to gauge if that happens. Hospital records and the records doctors keep simply don't interact in a way that would make it clear to a primary care physician that such an appointment should be booked. Nor are hospital-based doctors informed about whether their advice was heeded.

So Ko and some colleagues from ICES used anonymous medical data on nearly 57,000 high-risk Ontarians who went to hospital for chest pain between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2010 to try to tease out some answers.

They could not do a randomized controlled trial -- considered the gold standard of medical evidence -- because it would have been unethical to ask some patients not to seek followup care.

The researchers looked at whether the individuals had a followup appointment within 30 days, and with which kind of physician. They also looked to see whether diagnostic tests and medications were prescribed as well as whether those patients were still alive or had suffered a heart attack a year later.

Only 17 per cent of the people saw a cardiologist within the month after the event. The bulk -- 58 per cent -- saw a primary care doctor. But 25 per cent got no followup care within that 30-day window.

Most people were still alive a year later, regardless of whether they saw a doctor or not.

Among those who saw a cardiologist, the rate of death or heart attack was 5.5 per cent at one year. For those who saw a family physician, the rate of death or heart attack was 7.7 per cent. And among those who didn't get followup care, the rate was 8.6 per cent.

The differences between those rates works out as follows: People who saw cardiologists were 21 per cent less likely to have died or had a heart attack a year later than those who got no followup care. And those who saw a family doctor were 15 per cent less likely to have had a heart attack or died than people who didn't see a doctor about their heart problems.

The patients whose records were included in the study had what is called a higher baseline risk of heart disease. They had one or several of the following conditions which raise their chances of having heart attacks and strokes: diabetes, hardening of the arteries, unstable angina, heart failure or unusual heart rhythms. Also included were people who had undergone bypass surgery, had stents inserted to open blocked arteries or had a cardiac defibrillator implanted on their chest wall.

Ko, who is a cardiologist at Toronto's Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, said he was surprised to see that a quarter of people with these conditions didn't get followup care after a serious chest pain incident.

"These are to me high-risk patients. They were serious enough to get to the hospital with chest pain. And yet within a month they didn't look like they had anything done," he said.

The study was funded by the Kuk Family Cardiology Research Fund and grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.