An experimental new approach to fighting the deadliest form of skin cancer -- melanoma -- is providing some strikingly encouraging results. And now researchers are hopeful they might be able to use the same approach against other cancers.

The new approach uses something called immunotherapy medications that are designed to trigger the body’s immune system, allowing it to fight the cancer on its own.

Several clinical studies are testing the drugs and the results are already a key focus at this year's American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in Chicago.

Much of the attention is trained on immunotherapies that work to disable a key protein called “programmed death 1,” or “PD-1.”

The protein, emitted by tumours, allows cancer to evade the immune system’s killer T cells. But once these new drugs shut PD-1 down, the T cells recognize the cancer and begin to multiply and attack it.

Trent Krajaefski is one of those who’s benefited from the new approach. Two years ago, the now 35-year-old suddenly developed a blinding headache that doctors discovered was a brain tumour.

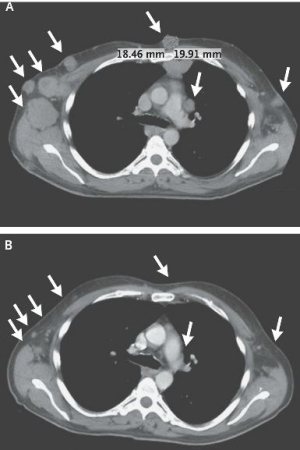

Further tests revealed his tumour started out as melanoma that had spread into his lungs and abdomen, as well as his brain.

“We never found the original spot where it started, but the trend is that (melanoma) moves low to high. So it started somewhere lower on my body, went through my lungs and up into my brain,” Krajaefski says.

Krajaefski was devastated to learn that his prognosis for metastatic, Stage 4 melanoma was not good: most patients don’t live longer than a year.

“You immediately realize that there is no cure and you don’t know how much time you have left, especially when it is in an area like the brain,” he says.

Doctors tried radiation to shrink the tumours as well as chemotherapy to kill the cancer cells -- all with little effect. Krajaefski was even part of a clinical trial for another therapy. It worked for a while, but then stopped.

Finally, Krajaefski signed up for a trial of the anti-PD-1 drug, lambrolizumab. Within a few months, his tumours started shrinking.

Krajaefski’s last scan showed that 80 per cent of the tumours in his lungs and abdomen had disappeared.

His energy levels are also up and he’s back to work full-time as a munitions expert with the Canadian Forces. He and his wife are now looking forward to buying a new home near Ottawa.

“The way ahead for me is just carry on. Keep on going until they tell me there is no cancer left or they find something else,” he says. “I am just happy going forward day to day.”

Dr. Marcus Butler, an oncologist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre who worked on the study, says Krajaefski is a “star case” because the drug shrank his tumours so well.

He says while not all patients have seen the same results, many are doing well and not seeing their disease worsen.

“The reason we are excited about this drug is that the response rate seemed to be very high,” he said. “About 50 per cent of patients had their tumour shrink significantly, and that is very exciting because it could mean a lot more patients will live longer on this drug.”

The results of the study were published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine. Of 135 advanced melanoma patients who tried the drug, 38 per cent saw their tumours either shrink or stop growing. Among those receiving the highest dose of the drug, 52 per cent saw a response.

Side effects included fatigue, nausea and diarrhea, all of which the researchers considered “low-grade,” and none of the side effects of standard chemotherapy, such as hair loss.

Butler says he and his team are working to understand why many patients do not respond, exploring the idea of combining immunotherapies together or with other treatments.

Jonathan Bramson, the director of McMaster’s Immunology Research Centre, says he’s hopeful these new immunotherapies are just the beginning of whatcould be a powerful way toactivate the immune system against cancer.

“We’re seeing seen remarkable outcomes and evidence of what we long believed: that the immune system can fight cancer,” he says.

Bramson added that he’s not just hopeful,but “phenomenally” excited.

“I’ve been a scientist in this area for 20 odd years, and much of the promise has come from animal studies. To be living in an era where we have evidence the immune system can treat cancer, it’s a very exciting time.”

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip