TORONTO -- A Canadian-led international research team has identified several new genetic mutations that appear to be linked to autism spectrum disorder, using a method that looks at the entire DNA code of affected individuals.

The method is called whole genome sequencing, and the researchers believe they are the first to use it to take an in-depth look at genetic alterations associated with autism spectrum disorder, or ASD.

The disorder, which affects about one in every 88 children in North America, encompasses a wide range of developmental conditions that can cause significant social interaction, communication and behavioural disabilities.

More than 100 clinical disorders, from Asperger's to Rett syndrome, fall under the ASD umbrella. Those with the disorder also often have associated medical conditions, such as a gastrointestinal disease or seizures.

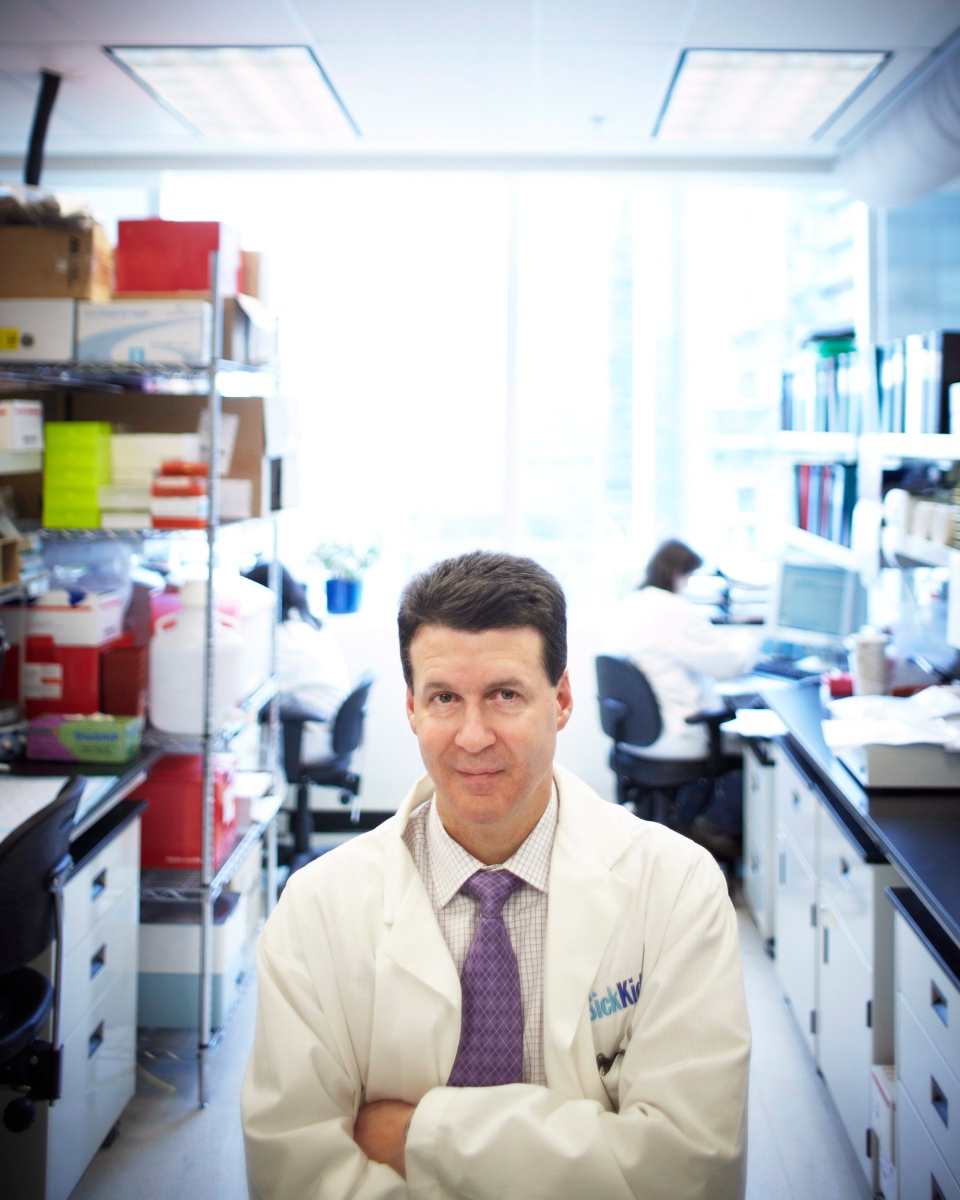

The $1-million pilot study, published online Thursday in the American Journal of Human Genetics, was led by scientists at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children and involved whole genome sequencing of 32 Canadians with ASD, their parents, and in some cases siblings and other relatives.

Researchers identified genetic alterations "likely to be associated with ASD or its accompanying clinical symptoms," said principal investigator Stephen Scherer, director of the Centre for Applied Genomics at Sick Kids.

Whole genome sequencing is a laboratory process that "reads" the roughly three billion base pairs -- think of them as letters in a very large book -- that make up a person's DNA, including an estimated 30,000 genes. The technology can detect mistakes -- or mutations -- in how those letters are put together.

The technology allowed the team to uncover genetic risk variants linked to ASD symptoms in half of the participants. Standard technologies -- which sequence targeted snippets of a person's DNA -- had only been able to identify genetic alterations in about 20 per cent of autism patients tested.

The study pinpointed mutations in four newly recognized genes, nine genes previously linked to autism and eight candidate autism risk genes. Some families were found to have a combination of these genetic changes.

"We can't say we found in those individuals the cause of autism," stressed Scherer.

"What we're saying is, based on this pilot study, if you take 100 new diagnoses of autism and we sequence their genomes, in 50 per cent ... we would find a genetic variant that either explains their autism or some of the associated medical complications that come along with that," he said.

Researchers were able to zero in on so-called spontaneous mutations -- where an altered gene occurs for the first time in one family member -- but also let them pinpoint mutated genes inherited from one parent or the other.

"We find that in 10 out of the 32 families, which is 31 per cent, we find an inherited genetic variant that would never have been reported on using one of these other technologies," Scherer said of narrower DNA sequencing methods.

Being able to study the entire genome gives scientists the ability to probe more deeply for at least the genetic underpinnings of ASD, which may combine with environmental or other factors to create the disorder in some children.

"This is the technology we've been waiting for since I was a student," said Scherer. "We've been looking at the genome in a piecemeal way. This gives us all the genome."

Dr. Hakon Hakonarson, head of the Center for Applied Genomics at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, said the findings aren't unexpected, as whole genome sequencing is "a very sensitive technology."

"They find some new, novel variants that are likely to have a role in the pathogenesis of autism in these individual families," said Hakonarson, who was not involved in the research.

"It's a well-done paper in that context ... and they've obviously identified some interesting genes, and at least some of them are very likely to be players and help certain families in the future."

Indeed, Scherer and his U.S. and Chinese co-authors say the technology isn't just an advanced research tool, but ultimately a way of empowering families affected by ASD.

"From diagnosis to treatment to prevention, whole genome sequencing efforts like these hold the potential to fundamentally transform the future of medical care for people with autism," said Dr. Rob Ring, chief scientific officer at Autism Speaks and a study co-author.

Because ASD can come in many guises and be such a complex condition, getting a definitive diagnosis can take months, even years in some cases, as the child is taken to multiple specialists, Scherer said.

Whole genome sequencing could shorten the length of that diagnostic path by unearthing genetic clues that might help explain ASD-like behaviours in a child.

"And that's critical in autism. You want to get a formal diagnosis as quickly as possible so you can enrol the kids in the proper intervention programs," he said. Early treatment can help a child overcome deficits in language and social skills.

"We can deliver this test in essentially a week and we can process dozens of samples at the same time," he said.

While the cost of whole genome sequencing has dropped dramatically since a human's full complement of DNA was first analyzed in 2001 at a price of $100 million, it remains expensive, running at close to $5,000 per person. The goal of researchers and medical geneticists is to get testing below $1,000.

Testing would help families with one child affected by ASD to decide whether to have more children. About 18 per cent of families that have a first-born child with ASD will have a second one with the neurological disorder, which affects about four times as many boys as girls.

The researchers have begun working on the next phase, a five-year international collaboration that will involve sequencing the entire DNA of 10,000 families around the world affected by autism, including 1,000 in Canada.

The ultimate goal, of course, is to find all the genes and all the genetic variants within those genes that underpin ASD, said Scherer.