TORONTO -- At a clinic in Surrey, B.C., some newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients are receiving a therapy that few other Canadians can get.

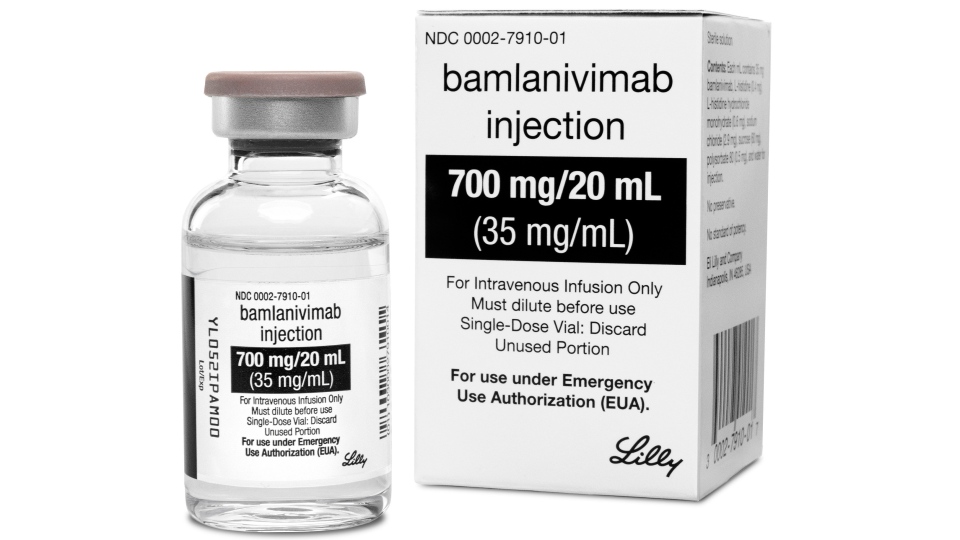

The Canadian-made treatment is called bamlanivimab, and it involves infusing patients with monoclonal antibodies within three days of testing positive, all with the aim of preventing their illness from progressing into life-threatening.

Bamlanivimab has been approved and used around the world in more than 400,000 patients, but the treatment is contentious due to recent concerns from the FDA and Health Canada regarding its effectiveness.

But despite concerns that the drug doesn't work against some of the new variants, it does help prevent patients infected with the variant first identified in the U.K. from ending up in hospital with severe disease — something many doctors across the country say is critical considering that B.1.1.7 is the dominant variant circulating in Canada.

Dr. Greg Haljan, head of critical care at Surrey Memorial Hospital and lead investigator in this new B.C. clinic at Peace Arch Hospital, told CTV News that one of the main misconceptions he and his team are contending with is the assumption that the treatment isn’t safe.

“Many patients, family physicians and even pharmacists, don't know that that the medication is safe,” he said. “We are really struggling with a lot of the public discourse around this medication. I think there's been a lot of confusion.”

The clinic is giving the drug to 300 patients who qualify, and will be following their results over the months after the treatment.

The treatment was first approved by Health Canada in November, and almost 30,000 doses were purchased by the government, but it has still been hard to get in most parts of Canada because it takes two hours to infuse and monitor patients who are COVID-19 positive.

Patients also have to be identified in a very short window of time after testing positive.

“We had to capture these folks at the peak of their contagiousness and bring them somewhere to receive therapy and ensure that they're not exposing other patients or other staff members,” Haljan said.

Despite the logistical difficulties, researchers are hoping to expand the use of the treatment.

“We think that Canadians deserve every option that's available to them as far as care for severe COVID, or mild COVID for that matter,” Dr. Anand Kumar, an intensive care specialist and an associate professor with the University of Manitoba, told CTV News. “This is a product that is available, it's on the shelf. And it's not being utilized.”

He pointed out that with the current burden on ICUs, more focus needs to be on how to keep COVID-19 patients out of hospital.

“Given the incredibly high level of stress that the ICUs are under, I think that everything and anything that we can do that can decrease the chance of patients progressing to the point that they need ICU care is warranted, right now,” he said.

“The risk of of its use is low, the potential benefit is high, and we're in a critical situation when it comes to capacity for severely ill patients.”

So far, the B.C. clinic has not logged any serious allergic reactions in response to the treatment, and their interim results have supported the safety of the drug that was found in earlier tests.

When 67-year-old Isherpal Dhaliwal of Surrey, B.C. heard about the clinic after he tested positive, he jumped at the chance.

He is considered at high risk of severe outcomes for COVID-19 because of a previous heart condition and his age. Since getting the infusion on April 19, he’s had no symptoms.

“My temperature is gone, everything is gone,” he told CTV News.

The clinic is focusing on those with mild symptoms in the first few days of their illness who are also at risk of severe illlness. They will be tracking the patients to see if they can keep one out of every eight patients out of hospital, as was found in a recent U.S. study on the drug. https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciab305/6224410

“You're looking for people who have mild disease at the moment, but are debilitated in different ways, that can mean […] immunosuppressed, that can mean they've got chronic organ failure, etc,” Kumar said. “These people are at high risk for progression, and they're high risk for a bad outcome if they do progress.”

The controversy around the medication stems from its potential to fail as a treatment when it comes to several variants of concern.

Health Canada warned last week that the therapy doesn't protect against numerous variants with two specific mutations, including variants that first emerged in South Africa, Brazil, California and New York.

The agency said this failure was identified through “global surveillance,” and specified that “Bamlanivimab is expected to retain neutralizing activity against the United Kingdom (UK) origin B.1.1.7 variant.”

Of the three variants that have been detected in Canada, there are more than 100,000 more cases of B.1.1.7 than any other variant. Around 116,000 cases of the B.1.1.7 variant have been identified in Canada, while there have only been 4,469 cases of the P.1 variant and just over 700 cases of the B.1.351 variant.

Researchers say that since the medication is safe, and the B.1.1.7 variant is circulating so widely, the benefits of expanding the usage in Canada are evident.

“It does have good activity for the majority, if not the vast majority, of the cases that are being seen in most of Canada,” Kumar said. “I don't see a downside.”

Haljan said his interest in this treatment began in the second wave of the pandemic. It made sense early in the pandemic that doctors and scientists were focused on treating those that were severely ill, but as time wore on, he wondered why “we weren't doing a lot of research in the community to prevent progression to hospitalization.

“I found it really frustrating that we were waiting until patients were so sick that they needed to be admitted to hospital before we were offering them any therapies for COVID,” Haljan said.

Delivering this kind of treatment is difficult, he acknowledged, but it being challenging isn’t a reason to back off.

“I think during the pandemic our patients expect us to do that hard work,” he said. “It's not as simple as just getting the medication, it's about identifying patients early. It's about ensuring it's done safely.

“And I think every[one] everywhere in Canada should have an opportunity to get this medication, and we should be following the patient outcomes as well.”

One detail from this new project that Haljan highlighted was that researchers will not only be focusing on the patients’ immediate response — such as whether they progress to needing hospitalization or whether the medication keeps their illness down — but also on the long-term.

“The question we're asking that nobody else has asked yet is can medications like this reduce the consequences of COVID?” Haljan said. “We know that many patients suffer symptoms for many, many months after COVID.”

They will be following up with patients not only in the weeks after the initial treatment, but also six months after.

“What are their symptoms, what's the quality [of] life in six months?” Haljan said. "We have patients who are part of our study and that's the question that was most important to them.”

The B.C. researchers project that they will have more data within a month — results that they hope will bolster confidence in this Canadian-made therapy.