TORONTO -- As passengers begin to return to airports in larger numbers, masks strapped on and hand sanitizer abounding, one question still remains murky: what is the risk of catching COVID-19 on a flight?

A recent case study is providing insight into who is potentially at risk of contracting COVID-19 on an airplane if there are infectious individuals onboard, and how seating position and airflow could play a role.

Released Tuesday as a research letter in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the research looked specifically at one single commercial airline flight from Tel Aviv, Israel, to Frankfurt, Germany, on March 9.

Researchers believe at least two individuals contracted COVID-19 from other passengers on the flight.

“In our study, both passengers with likely onboard transmission were seated within 2 rows of an index case,” the research stated.

But the story starts seven days before the plane ever left the ground. Out of 102 passengers on the Boeing 737-900 flight, 24 were members of the same tourist group.

Starting a week before their flight, the entire tourist group had contact with a hotel manager who would later test positive for COVID-19.

None of these individuals had received a COVID-19 diagnosis prior to boarding the flight.

Once the plane touched down in Germany, the passengers went through a medical evaluation. The 24 tourists received a throat swab to test for the novel coronavirus and additional interviews were set up with passengers four to five weeks later.

Seven people from the tourist group tested positive for COVID-19 during that first throat swab at the airport, making them the “index cases”. Four of them had been experiencing symptoms on the plane, two had yet to experience symptoms, and one would remain completely asymptomatic.

Anyone seated on the plane within two rows of these seven passengers, as well as anyone else throughout the plane who reported symptoms, were offered antibody tests in the weeks after the flight.

Of the 78 remaining passengers who had been exposed to the tourist group on the plane, 71 consented to follow-up interviews.

One passenger reported testing positive through a throat or nose swab taken 4 days after the flight, and didn’t recall having displayed any symptoms. An antibody test and a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) confirmed both had positive results.

The passenger did not believe they had come into contact with anyone who had COVID-19 before or after the flight, making the flight itself the likely site of where they contracted the virus.

The individual who makes up the second likely case of transmission experienced a headache, muscle aches, and hoarseness starting five days after the flight and quarantined themselves. An antibody test detected the novel coronavirus, although the PRNT results to double check the antibody test were “borderline.”

A third person experiencing symptoms had previous contact with a COVID-19 patient, meaning it was not clear whether they could have contracted COVID-19 before they got on the plane.

A detailed look at the seating chart shows that the two likely cases of transmission were seated across the aisle and within two rows from the index cases.

Three of the index cases who were symptomatic on the plane were sitting right next to each other on the right side of the plane, just one row behind one of the likely cases of transmission, who was seated in the aisle seat on the left side of the plane.

But those who likely contracted the virus were not just those who were closest to the index cases.

The second likely transmission was a passenger sitting in the far window seat on the left side of the plane, with two seats and the aisle in-between them and the index cases, all of whom were seated on the right side of the plane. The person sitting in the middle seat next to them, closer to the index cases, did not test positive, according to the research.

“The airflow in the cabin from the ceiling to the floor and from the front to the rear may have been associated with a reduced transmission rate,” the researchers stated. They noted that for previous viruses, such as SARS and influenza, transmission has been found to extend beyond the two row perimeter that researchers look at most closely in these cases.

“Our findings do not rule out airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in an airplane cabin.”

It’s important to note that the flight studied was in the air long before airlines were taking precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19, such as requiring passengers to wear masks for flights. None of the index cases were wearing masks.

“It could be speculated that the rate may have been reduced further had the passengers worn masks,” the researchers wrote.

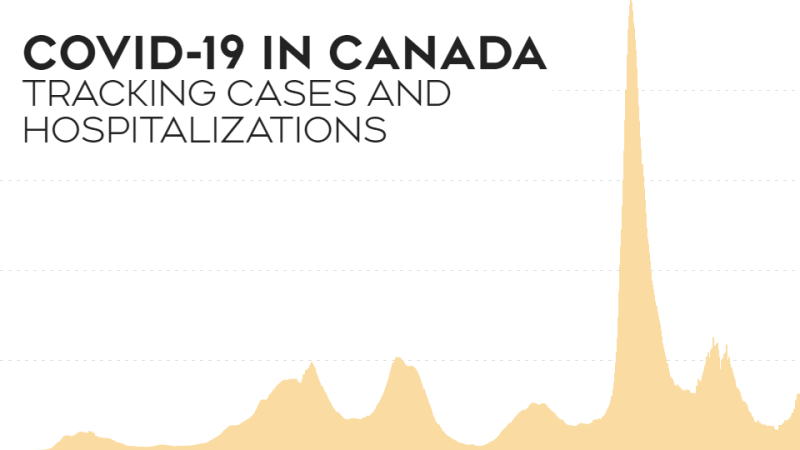

The number of people who have actually contracted COVID-19 on an airplane is believed to be relatively small so far considering that individuals with COVID-19 are still taking flights into Canada and between provinces.

Eighteen of the flights arriving to Canada from international destinations since the start of August alone had people on board with COVID-19.

A study published in late July also showed that those travelling on a train are at risk for contracting COVID-19, and that the most dangerous seats are those directly across from or beside an infected person.