TORONTO -- Tests for COVID-19 offering the promise of returning health-care workers to the front lines are a hot topic among Canadian doctors, but some say there must be further testing before these blood tests can be used widely.

“We have to see how these tests function in the Canadian context with our present prevalence and we have to test these here,” said Dr. Michael Silverman, an infectious disease specialist at London Health Sciences centre in London, Ont.

While traditional COVID-19 testing strategies typically involve a nasal swab to detect a current infection, blood tests looking for antibodies are being developed rapidly.

Some are already being used in Europe and the U.S. They use blood samples, some as small as a finger prick to look for antibodies, parts of the immune system produced after the body has fought off a virus.

Antibodies usually can be detected five to seven days after infection.

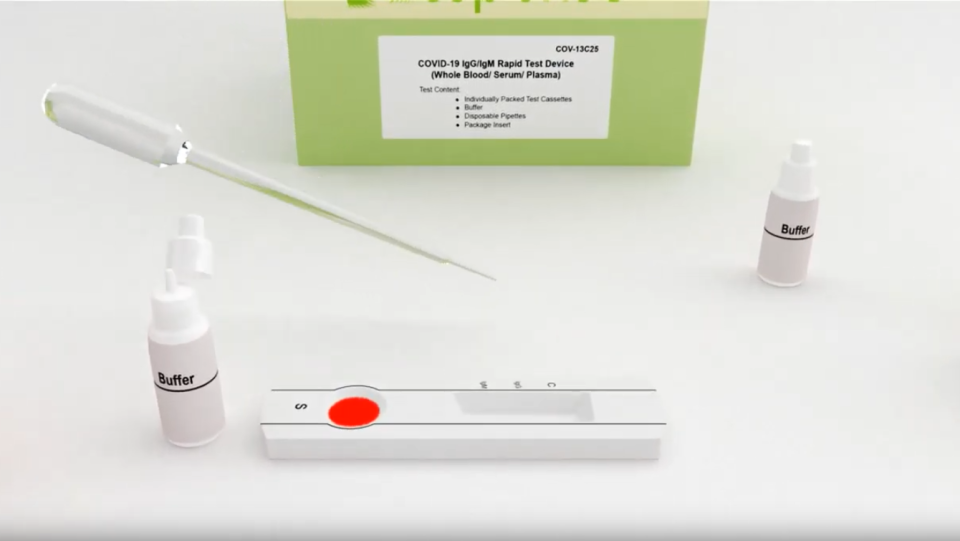

One of the companies vying for sales is Markham, Ont.-based biotechnology firm BTNX. Its test looks like a small strip with windows in which patients put a small drop of blood followed by a chemical to process the sample.

“The test itself is different than what a lot of people are familiar with right now with laboratory testing, in that it's a blood test, and it's read very similarly to a pregnancy test, so the results are actually in 15 minutes,” Mitchell Pittaway, the company’s chief financial officer, told CTV News.

By testing for antibodies, doctors would be able to tell if someone has potentially developed an immunity to COVID-19, with Pittaway saying early tests of his company’s kit show 97 per cent accuracy among people with symptoms.

“We see very high accuracy once we get closer to the one-week mark where the body's been able to generate those antibodies,” he said.

But Pittaway said Health Canada told him the tests could not be sold in Canada until a “national strategy” on antibody testing can be developed, an approach based on a World Health Organization recommendation to be cautious on the use of antibody testing until the accuracy of these tests is confirmed.

Earlier this month, the government in the United Kingdom admitted that COVID-19 antibody tests generally don’t work.

Silverman agrees with health officials in the U.K. and calls the accuracy of the tests “suboptimal.” He believes more studies should be done before the results of can accepted, particularly when it comes to telling someone if they are in the clear or not.

Silverman is part of a Canadian team testing another blood antibody test to see how many health-care workers have already been infected with COVID-19.

“Although the antibody test may not be accurate enough for an individual to say: ‘You definitely have been infected’ or ‘You definitely have not,’ when we do it on a large number of people, we can get an idea of how much infection is in the community,” he said. “That can help to know where we're at in terms of the epidemic.”

“If you're asking to do the test on one person and make decisions for that one person based on that test, we're not there yet,” he said. “Hopefully we will be and there's an enormous amount of effort to get there in the near-to-mid future, but we're not there as of today.”

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, also said Tuesday that more testing is needed.

"A few countries have taken antibody tests and found out, after buying millions of them, that they actually don't work,” he said in an interview with The Associated Press. “So I give that as a caveat because we need to get a test that works and that's reproducible.”

Still, some doctors believe the Canadian antibody test should be used locally instead of being shipped to the U.S and Europe where the test isn’t officially approved, but is allowed for use.

Dr. Jean Carruthers, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of British Columbia, recently penned a letter to the federal government, urging it to allow the test to be used here. The letter has since been signed by more than 80 doctors.

“I'm really, really concerned because we have the means to have this test available to Canadians, made in Canada, and this is being shipped in the hundreds of thousands to the United States,” she said. “What about Canadians?”

Carruthers added that having even preliminary knowledge of who might have already had the coronavirus infection could help the Canadian healthcare system and the Canadian economy.

“If they were immune and knew they were immune, they could go back to work, the health-care workers on the front line could know that they were immune to the virus,” she said. “It would be amazingly helpful to Canadians.”

Pittaway says he understands the slower approval process in Canada and welcomes further study into the product.

“From our perspective, we want to get this into market as soon as possible, but at the same point if the officials want to take a bit more time in order to do these extra studies and to take part,” Pittaway said. “At the end of the day, we just want the government to be confident in the product and the testing protocols that they put in place,” he said.

On Sunday, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney tweeted that he may break rank with Health Canada’s position and has directed staff to consider using tests or treatments "that have been approved by the high standards of at least one credible peer country's drug agency.

Health Canada did not respond to a request for comment from CTV News.

With files from The Associated Press