TORONTO -

Experts are warning that the COVID-19 pandemic could usher in a wave of increased dementia and Alzheimer’s worldwide through the ‘Trojan horse’ of neurological symptoms associated with long COVID, also known as long-haul COVID-19.

Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), which represents more than 100 Alzheimer’s and dementia associations, is calling on the World Health Organization and governments across the globe to invest funding into more research on the link between long COVID cases and dementia.

In a press release, ADI explained that even before COVID-19, it was predicted that dementia cases would rise from 55 million to 78 million by 2030, and associated health-care costs could rise to $3.5 trillion annually.

Now, experts believe millions more than that could face an accelerated risk of dementia due to COVID-19’s impact on the brain.

“Many dementia experts around the globe are seriously concerned by the link between dementia and the neurological symptoms of COVID-19,” Paola Barbarino, CEO of ADI, said in the release.

“We urge the WHO, governments and research institutions across the globe to prioritise and commit more funding to research and establish resources in this space, to avoid being further overwhelmed by the oncoming pandemic of dementia.”

Dementia is a general term describing symptoms that affect memory and executive functioning. A person with dementia may struggle to remember things, process thoughts and make decisions in a way that interferes with day-to-day activity. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia. According to Alzheimer’s Association, more than 747,000 Canadians live with dementia.

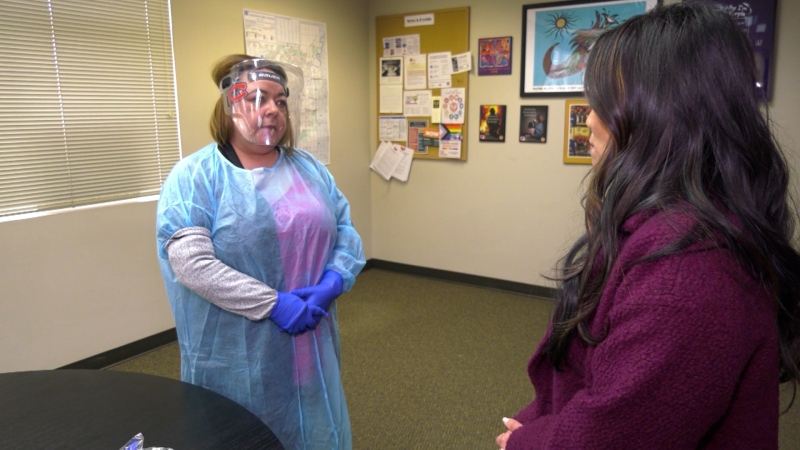

Dr. Alireza Atri, a leading expert in dementia, and part of a working group of scientists looking to study this issue, told CTVNews.ca over email that he first started to notice the problem last fall, when several patients in their 50s showed fast deterioration of their cognitive functions.

“All had been ill with COVID – mostly with mild illness, though one had been in the hospital for four days — a few months prior to the steep decline in their cognitive functions,” he said. "None of the patients or their family members had thought to link COVID with their mental decline.”

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many of those who survive the virus have reported lasting cognitive impairment. A June survey looking at 1,000 Canadians who previously tested positive for COVID-19 found that more than 80 per cent of respondents had cognitive symptoms last for at least three months, while almost half said that their symptoms had lasted 11 months or longer.

Other studies have found that those hospitalized with COVID-19 experienced neurological symptoms, with one study across 13 countries finding that 82 per cent reported neurological issues.

And new research revealed at the recent Alzheimer’s Association International Conference found specific biomarkers associated with dementia and Alzheimer’s in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the study, which looked at plasma samples from 310 COVID-19 patients admitted to New York University Langone Health, researchers observed that biomarkers of neuronal injury, neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease were found at higher levels in COVID-19 patients who had reported neurological symptoms.

Atri said that with the combination of studies showing neurological symptoms in COVID-19 patients, as well as autopsy results showing that the brain was affected, he and his colleagues started to realize the extent of the impact.

“It dawned on us that COVID was likely causing a massive acceleration in cognitive decline in individuals who were harboring Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in their brains, but who, up to that point, were mostly combating it and showing very little symptoms,” he said. “COVID likely set fire to the Alzheimer’s kindling and fanned small flames that were already there, thus tipping their mental function over the edge.”

In the release, he outlined the neurological symptoms of long COVID that are worrisome, such as loss of taste and smell, brain fog and difficulties with memory, concentration and language.

“COVID-19 can cause damage and clotting in the brain’s micro vessels, immune dysfunction and hyperactivation, inflammation, and, last but not least, direct viral brain invasion through the olfactory pathways,” he said in the release.

“Simply put, if you have a fortress and an enemy puts holes in your walls, you’re less likely to be able to withstand current and future attacks. COVID-19 opens the gates in the same way that the Greek soldiers hiding in the wooden horse did. It gives easier access to things that can harm your brain.”

He told CTVNews.ca that the decline that leads to Alzheimer’s generally starts 15-25 years before symptoms show up, and that diagnosis takes a couple years after that in most cases.

The processes that lead to dementia “involve the clumping of toxic proteins in the brain that ultimately overcome the brain’s defense mechanisms,” he said.

“With the spreading of these ‘fires’, including inflammation, there is disruption of energy use and destruction of brain connections and cells.”

Although it’s not yet fully understood how COVID-19 impacts the brain, “anything that diminishes cognitive resilience allows the impact of neurodegenerative processes to accelerate.”

So a person who may be vulnerable to developing dementia, or may have presented with it later in life, could start showing symptoms earlier, experts believe.

“By taking a COVID-19 hit to the brain, it can be like pouring fuel or starting new fires in the brain – and thus add to a person’s risk or accelerate their trajectory of decline,” he said.

In the short term, experts expect to see a temporary dip in dementia levels worldwide, simply because a large majority of those suffering from dementia are older, and COVID-19 has killed so many of the elderly. But they expect that we will see dementia impacting more and more people moving forward.

How soon we will see these increases in dementia levels depends on how quickly we can gather the resources to study it properly, Atri said.

“But first, we need to let people know that this is a likelihood,” he said.

More research into the issue is important in order to make a plan for how to address a coming increase in dementia patients, Barbarino said.

“People at risk of developing dementia need to know about the potential impact of long COVID on their brain health,” says Barbarino. “We need people to be aware of the possible link between long COVID and dementia, so they know to self-monitor for symptoms and catch it in its tracks. Measures must be put in place to protect them.”

For those who are concerned about dementia, a full list of symptoms is available on ADI’s website.

Atri suggested that in addition to investing in research, we should be investing in clinical care for those with dementia, as well as those with long COVID. But awareness is the first step to diagnosis — and it seems this is something we need to be watching out for during this pandemic.