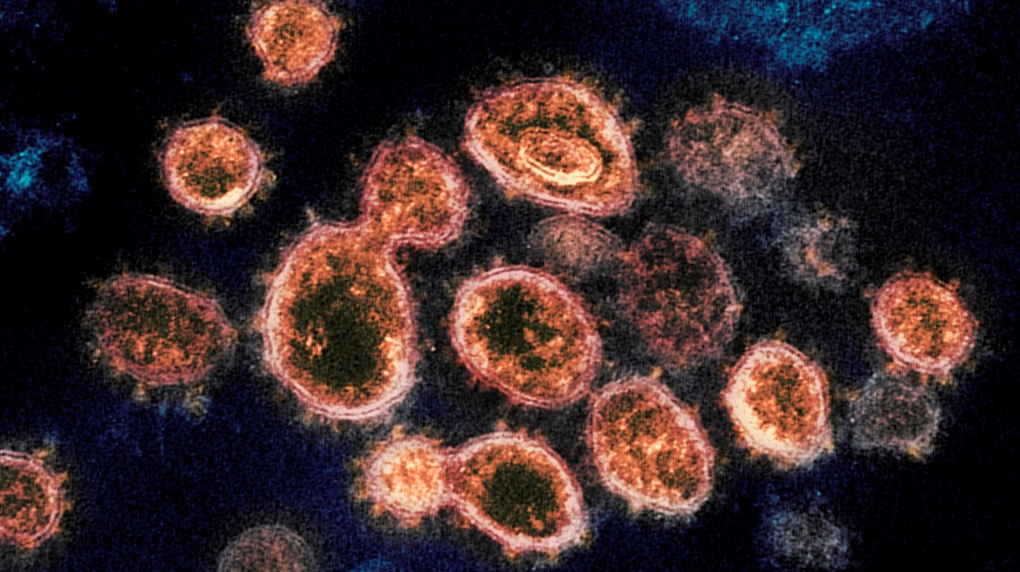

TORONTO -- A case study involving a patient in his 70s has raised the possibility that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, could evolve in immunocompromised individuals infected over an extended period of time and treated with convalescent plasma therapy, according to a U.K. paper published in the journal Nature on Friday.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and University College London followed a patient who was hospitalized over the summer of 2020 and treated with remdesivir and convalescent plasma therapy for nearly three-and-a-half months. During the course of his treatment, they noticed “a repeated evolutionary response by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of antibody therapy.” Specifically, mutations in a spike protein similar to those in the B.1.1.7 variant first detected in the U.K. were found following the patient’s plasma treatments.

The plasma therapy works by taking donated blood from a person who has recovered from an infectious disease to treat someone else sick with the same illness. The blood is processed so that only the plasma and antibodies are left. The treatment has been used in patients with COVID-19 to try and help them better fight the virus.

But there is no evidence that it works in severe cases of COVID-19, the researchers noted in their paper, adding that the use of convalescent plasma in different stages of infection remains experimental and should be used with “rigorous monitoring.”

“The data from this single case report might warrant caution in use of convalescent plasma in patients with immune suppression of both T cell and B cell arms,” the study said, referring to key white blood cells that work together to fight infection.

“Our data highlight that infection control measures may need to be tailored to the needs of immunocompromised patients and also caution in interpretation of CDC guidelines that recommend 20 days as the upper limit of infection prevention precautions in immune compromised patients who are afebrile [not feverish].”

Over the course of 101 days, the researchers collected 23 virus samples from the patient. For the first 57 days, scientists did not see significant change in the virus overall when the patient was treated with two courses of remdesivir.

But between day 66 and 82, after the patient received his first two rounds of convalescent plasma, they noticed a particular variant emerge and dominate that had a mutation that is also found in B.1.1.7. Over time, that variant faded and the original became dominant again, with samples showing there was “competition” between the different mutations. A third convalescent plasma treatment brought back the same variant again, however.

The data showed a fast evolution for SARS-CoV-2 during the plasma treatment, with evidence that these variants were two times less susceptible to neutralizing antibodies, the authors wrote in the study, but cautioned against drawing generalizations due to the limitations of the single-case study.

“The effects of [convalescent plasma] on virus evolution seen here are unlikely to apply in immune competent hosts where viral diversity is likely to be lower due to better immune control,” the researchers said.

The treatments failed to help improve the patient’s condition and the man died from multiple organ failure 102 days after he was admitted.