TORONTO -- A Canadian-made COVID-19 antibody treatment is sitting on hospital and pharmacy shelves amid the country’s third wave of the pandemic because doctors say a plan on how to administer the drug was never made.

“It's actually very frustrating that we have a therapy available to us that we're not actually able to use,” said infectious disease expert Dr. Deepali Kuma.

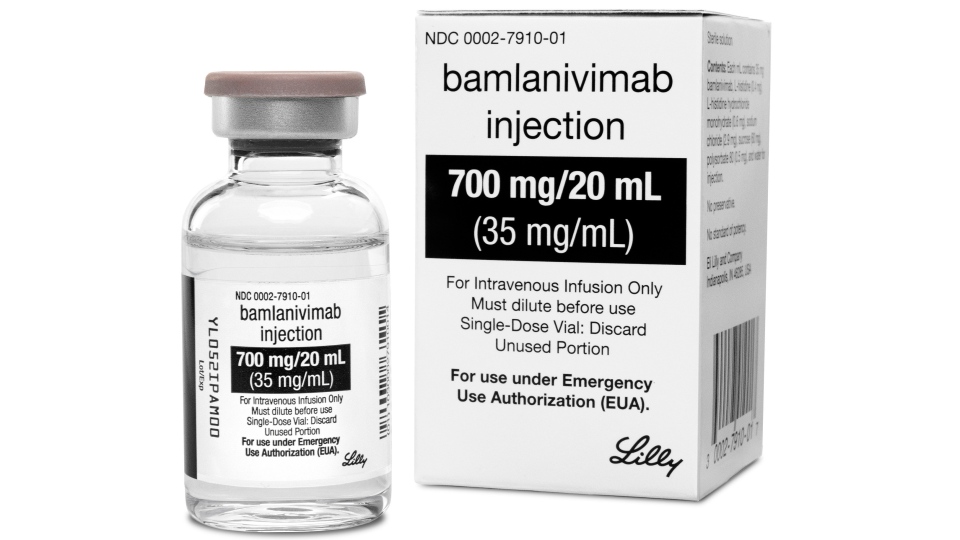

Bamlanivimab is a monoclonal antibody directed against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The drug mimics the immune system's ability to fight off the virus and was developed by AbCellera Biologics Inc. in Vancouver with the support of the federal government, which had committed up to $175.6 million to the company in May 2020 to develop antibody therapies.

According to Health Canada, bamlanivimab may prevent symptoms from becoming worse and reduce hospitalizations in high-risk patients who are infected with COVID-19.

The one-dose treatment, which is sold by Eli Lilly Canada, Inc., can be used in health-care facilities such as hospitals, as it is given by infusion into the veins of patients.

As an antibody therapy, it is part of a major class of drugs normally used to treat diseases like cancer and rheumatoid arthritis, Sachdev Sidhu, a professor of molecular genetics at the University of Toronto, said in an interview.

“So as a method of treatment it is a … validated form, so this is not some off-the-cuff methodology,” said Sidhu, who specializes in antibody engineering.

Health Canada authorized the drug in November 2020 under the interim order respecting the importation, sale and advertising of drugs for use in relation to COVID-19.

According to Health Canada, 26,000 doses of the treatment were purchased for $40 million and distributed amongst the provinces.

However, almost none of those doses have been used.

Countries around the world have been using bamlanivimab to help keep COVID-19 patients out of hospital and reduce deaths for months. More than 400,000 COVID-19 patients worldwide have benefited from the drug, according to Michael McDougall, a spokesperson for Eli Lilly.

There are currently four other types of antibody drugs made by different companies, waiting for approval by Health Canada. The agency told CTVNews.ca that it was expediting these reviews, but could not give a more precise timeline on when a decision might be made.

According to AbCellera Biologics, studies have shown the treatment is effective against SARS-CoV-2, and the variant first identified in the United Kingdom.

Despite this, provincial health authorities have not yet made the treatment available to Canadians.

AbCellera Biologics CEO Carl Hansen told CTV National News it is “heartbreaking” that the drug is not accessible in Canada.

“We are proud to have contributed to a solution that's helping so many people around the world, but of course, it would be that much better if this was actually getting to people in our own communities, and was here to protect the ones that we love,” Hansen explained.

Hansen said that provincial government did not issue a plan on how to administer the treatment, causing doctors to leave it on shelves.

“To think that we've invented a therapy here and having taken the steps to bring it to patients is a failure of the system and one I think that needs to be corrected, as soon as possible,” Hansen said.

CTV News has reached out to provincial health units for comment, but did not hear back before this story was published.

To have a Canadian company get federal funding to develop the drug, see the drug approved, but then have it “sitting in the freezer -- that’s a mystery,” Sidhu said. “Canada is dropping the ball.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's recent revocation of bamlanivimab's Emergency Use authorization could cause some confusion with the public. A Health Canada spokesperson told CTVNews.ca via email that it was aware of the status change and noted that it was at the request of Eli Lilly, "given evidence that it is ineffective when used alone against certain COVID-19 variants of concern circulating in the U.S. and the availability of alternative therapies in the U.S. This action was not prompted by a safety concern."

"There is no change to bamlanivimab authorization in Canada and Eli Lilly has not requested that Health Canada revoke its authorization. Bamlanivimab used by itself is effective against the B.1.1.7 (UK) variant, which is the main variant circulating in Canada at this time," said Health Canada's Geoffroy Legault-Thivierge.

A CHALLENGE TO ADMINISTER

Matthew Miller, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., says the main issue with the treatment is that it is difficult to deliver.

Since it is given via intravenous, experts say Bamlanivimab has to be administered in a hospital setting within 10 days of developing symptoms. If a patient is too sick, the treatment cannot be administered.

“Unlike a pill, which can easily be brought home and taken by patients in their house, these antibodies have to be delivered by intravenous infusions which can take quite a bit of time and have to be delivered in specialized settings under medical supervision,” Miller said in an interview with CTV National News.

“So that presents a real logistical challenge to administering these drugs, especially to patients who are not yet very ill yet and wouldn't need to be hospitalized,” he added.

Kumar said the antibody therapy needs to be given “as early as possible in the course of the disease.” However, this can be challenging for those who may be too sick to get themselves to a facility in time.

“This means that if you have COVID, you need to get yourself to an emergency room or an infusion centre, where you can receive this monoclonal, and that's been very difficult to do,” Kumar said.

In the U.S., some places are also grappling with the logistics of using these drugs to help keep COVID-19 patients out of the hospital, while places like Johns Hopkins Medicine have set up outpatient monoclonal antibody therapy infusion centres to help deal with the treatment challenges.

Antibody drugs are also harder to make, Sidhu said, and at more than $1,500 a dose, bamlanivimab is not the cheapest medication. Still, experts have said it is less than the cost of hospitalization or being put in intensive care.

“The people it will help the most are those that have the littlest self-capacity to make antibodies,” said Sidhu.

IMPACT ON CANADIANS

Eighty-year-old John Tavel contracted the coronavirus in Ottawa last December. He told CTV National News that as his symptoms progressed, his greatest fear was dying from the disease.

“My fever was up to about 103, 103 and a half and … I was feeling horrible. So, my wife called an ambulance, and the ambulance took me right off to the hospital,” Tavel explained.

At the hospital, Tavel asked to be treated with Bamlanivimab. But doctors said they couldn't administer it.

Tavel said the doctor told him that they “don’t have a protocol” for the drug. Instead, he was discharged and told to take Tylenol to help get his fever down.

Tavel’s daughter, Robyn, who lives in Glencoe, Illinois, says the family heard about using monoclonal antibodies to help treat COVID-19 through their local news after then-U.S. President Donald Trump was given an antibody cocktail for the virus.

“As soon as we knew that that was available in Canada… We immediately knew that my father had to have it,” Robyn said. “The window of opportunity to administer this was just 10 days after someone had become very sick, and had been diagnosed, and so we had to get action.”

Robyn said she was frustrated when she learned that that her father would not have access to the treatment.

“To find out that there was a treatment available, that could be administered to my father to have him recover almost overnight or minimize the effects of the virus on his body, but not have it available was so upsetting,” Robyn said.

Tavel’s symptoms continued to get worse, and he eventually ended up back in hospital in a COVID-19 ward.

He says he eventually received a corticosteroid called dexamethasone, which made him feel a bit better. He was eventually discharged from the hospital to recover at home.

While Tavel did make a full recovery, he said he is still frustrated by the experience.

“We have [the drug] in Canada. People are dying, why don't we use it?” he said.

Robyn said she is thankful her father is OK after having contracted the virus, but worries about others who may become ill and need the antibody treatment.

“I still have other members of my family in Canada that potentially could become sick with this virus and I need to know that the government is acting quickly to make this treatment available to other Canadians,” Robyn said.

In the U.S. researchers are also exploring the use of monoclonal antibodies as a preventative option for vulnerable groups, such as immunocompromised patients who do not respond to the COVID-19 vaccines. These patients produce few or no antibodies either as a result of treatments for other diseases like cancer or because they were born with an impaired immune system.

Similarly, bamlanivimab was shown to lower the risk of contracting symptomatic COVID-19 among the residents and staff of long-term care facilities, according to the results of a phase III clinical trial by Eli Lilly conducted in collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

AN EXTRA TOOL TO FIGHT COVID

As infections continue to rise across much of the country, there are growing calls to tap this overlooked treatment to save lives.

Kumar says provincial leaders and health officials need to come together to figure out a way to implement Bamlanivimab into the health-care system. She said hospitals could set up mobile clinics and infusion centres to help get the antibody therapy out to those who could benefit from it.

“The new data that's coming, it shows that these therapies actually prevent death, and they prevent hospitalizations, and if we're going to reduce the burden on our emergency rooms and our hospital beds, then we really need to figure out how to use these therapies on a large scale,” Kumar said.

Kumar’s sentiment has been echoed by more than a dozen infectious disease doctors and members of parliament who signed a letter calling on all levels of government to work with clinicians and hospitals to increase access to monoclonal antibodies and expedite the approval of combination monoclonal antibodies.

“The evidence for these treatments is right now sufficiently robust – and the side-effects sufficiently limited – that Canadian physicians should be able to offer these treatments to eligible patients,” the letter reads.

“Indeed, the United States accepts this evidence and has already set up over 5,000 infusion sites which have administered this treatment to close to a million people.”

Dr. Michael Silverman, chief of infectious diseases at Western University in London, Ont. and one of the authors of the letter, told CTV News that he’s been frustrated with how difficult it has been to access the medication.

“We have a crisis in hospitals and we should really be using all the tools at our disposal to make sure we don't end up in a situation where our hospitals are overwhelmed,” he said.

Silverman also argues administering the drug doesn’t require additional resources if done properly.

"We don't need an ICU trained physician or nurse, we don't need a nurse who's able to run an internal medicine clinic,” he said. “This can be given by medics, this can be given by people who work at the Red Cross.”

Miller said the treatment could be especially helpful as Canada continues to face increased hospitalizations due to the disease.

“Any extra tools we have, especially in the wake of this very recent third wave, is helpful,” Miller said. “And I think these antibodies have particular benefits for people who may not yet have been able to get their vaccine.”

Hansen said it is necessary that Canada start administering doses of the treatment to prevent more Canadians from dying of COVID-19.

“We have a therapy here in Canada, it's one that has already been paid for, and it's sitting on the shelves. Meanwhile, people continue to get sick, and we should take every step that we can to make sure we are getting life saving therapies to patients as soon as possible,” Hansen said.