TORONTO -- A new antiviral drug, delivered in a single shot, could be a key tool to slow community spread, according to a Canadian study that shows the treatment may be able to help those with milder cases of COVID-19 recover from the infection much faster.

When our bodies are attacked by COVID-19, there are molecules called interferons that attack and kill the virus.

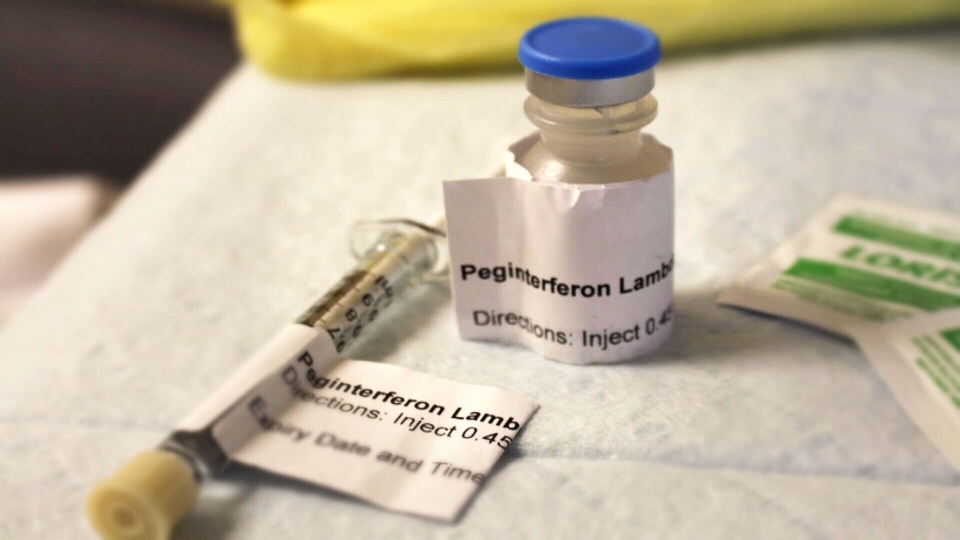

In a study of 60 COVID-19 outpatients — patients well enough to be at home in isolation — doctors in Toronto found that those given an injection of interferons called peginterferon-lambda were able to quickly reduce the amount of virus in the body.

“We were excited to see the potency of the antiviral effects,” Dr. Jordan Feld, one of the authors of the study, told CTV News. “So we really saw the virus levels falling much faster than what we've seen with most of the other treatments that have been studied to date.”

According to the study, published Friday in Lancet Respiratory Medicine, those injected were more than four times more likely to have cleared the infection altogether within seven days compared to patients who had been given a placebo shot.

In addition, far fewer patients who received the shot had their condition worsen to a point where they needed emergency care.

So how does it work?

Eleanor Fish, a professor of immunology at the University of Toronto and part of the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute with the University Health Network (UHN), has been studying interferons for decades, and explained to CTV News that they are a crucial part of the immune response.

“In response to any and all virus infections, our very first response is we make interferon — we make interferon alpha, interferon beta, interferon lambda,” she said.

However, the novel coronavirus actually has encoded factors that “blunt interferon response,” she explained. “And those individuals who get very severe disease life-threatening disease have compromised interferon responses.”

The way this new treatment works, she said, is that introducing more interferons to a mild case “overrides that inhibition [and] gets rid of the virus so you don't develop those life-threatening symptoms later on in the disease.”

In this new study, half of the participants were given placebo shots without the drug in them, and the other half received the actual treatment. By the end of the week, 80 per cent of the participants who had received peginterferon-lambda in their shot had an undetectable amount of virus left in their body, compared to 63 per cent of the placebo group.

The difference between the two groups increased when researchers accounted for the amount of viral load patients had to start with. The higher the viral load, the more impact the treatment had. When accounting for a high viral load, 79 per cent of those who received the treatment still had an undetectable amount of virus by day seven, whereas only 38 per cent of the placebo group did.

“What’s really important in this study is if you have a high viral load, if you come in with lots of virus in your respiratory tract, that’s when interferon lambda is most effective,” Fish said.

One thing that sets this treatment apart from others, according to Feld, is that it doesn’t rely on the sequence of the virus itself, which some other treatments do.

“The nice thing about interferon lambda is the way that it works is it's stimulating the body's natural defences.”

Scientists believe this means it would work the same way regardless of whether the virus had mutated.

“We would anticipate that this treatment would be equally effective against the […] usual COVID-19 and equally effective against these new variants that are emerging,” Feld said.

Feld is a liver specialist at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease with UHN, who had previously studied peginterferon lambda usage with viral hepatitis. Peginterferon-lamda is a long-acting version synthesized by Eiger BioPharmaceuticals.

If it was approved, the treatment wouldn’t be a solution for every case. Evidence so far suggests it works best when applied early on and with milder cases, in order to prevent severe illness. Patients with severe illness have inflammation in the lungs that could be exacerbated by interferon treatment if they received it after becoming seriously ill, Fish said.

Fish wasn’t part of this recent study, but has been involved with other studies looking at the possibility of interferon therapy to aid COVID-19 patients. She’s currently looking into whether early treatment can shut down transmission of the virus to post-exposure contacts, including others in a patient’s household.

She views Dr. Feld`s research as a promising step.

“It's pointed us in the right direction,” she said.

“Early on, interferons are effective not only in wiping out the virus, accelerating clearance in the respiratory airways, but also suppressing that inflammation. So treat early with interferon and you'll have good outcomes. If you treat later on, it's not going to be effective.”

There’s two major reasons why creating treatment aimed at those with mild cases is important, Feld said.

“If we catch the infection early, and we treat people and bring the virus levels down quickly, we can prevent that individual person from potentially getting sicker and going on to require hospitalization or more serious complications,” he pointed out.

But the main reason is that it’s a tool of prevention. Feld explained that if the virus level is brought down within an outpatient, it’s less likely that they will be able to pass on high levels of the virus to others.

“The idea here would be someone finds out they're infected, and very quickly gets this single small injection. And that's it. No additional treatment, no pills to take, no […] coming back to the clinic, one single injection brings down the virus level quickly, and hopefully then prevents them from getting sicker, prevents them from passing it on to others, and may even allow us to shorten the amount of time people have to be in isolation.”

Guilherme Silva was one of the study participants, and said he jumped at the chance to be in the study after he tested positive for COVID-19 in August.

The 29-year-old didn’t experience a lot of symptoms, but told CTV News that being part of the study felt purposeful.

“It's very good to hear that the test is coming with good results,” Silva said. “And especially being part of it […] just makes you feel good overall.”

While this recent study is promising, researchers caution that it’s still extremely early days, and the study was limited by its small scope.

Researchers are hoping to follow up with a much larger study.

Feld said it’s hard to know how much the treatment could cost since it hasn’t gone through the approval process yet — something still far off.

“But we would imagine that the overall cost of administering this would be much lower than a lot of the other treatments that are being evaluated for COVID-19,” Feld said.

In the meantime, other studies are underway on more patients in the U.S. and here in Canada, trying to unravel how interferons can help in the battle against COVID-19.

“I think we see there's a lot of potential,” Feld said. “I mean, obviously this is a first study.”