TORONTO -- They were prescribed a drug called Elmiron to help with their persistent bladder pain. But now two Canadian women are looking for justice, after they say the drug damaged their eyesight.

“It started out with distortion of lines, and that progressively got worse,” Catherine D’Andrea told CTV News.

D’Andrea works as an archeologist, and says she now has trouble seeing in dim lighting. Colour and brightness are diminished for her.

She was first prescribed Elmiron in 2004 for interstitial cystitis, a chronic condition that causes pressure and severe pain in the bladder. Elmiron, known generically as pentosan polysulfate sodium, is the only oral drug available for this condition, which affects hundreds of thousands of Canadians, most of them women.

But after years of taking the medication, D’Andrea says it has come at a cost.

“I am worried driving,” she said. “I am worried about my ability to walk up and down stairs.”

As an archeologist, she spends a lot of time looking at small objects to identify them, and her failing vision has made this increasingly difficult.

“Another part of my job involves going into very rugged, mountainous regions, hiking through uneven terrain, and so, again when you are looking down and trying to establish a good footing, it’s difficult when you’re not sure about what you’re seeing,” she said.

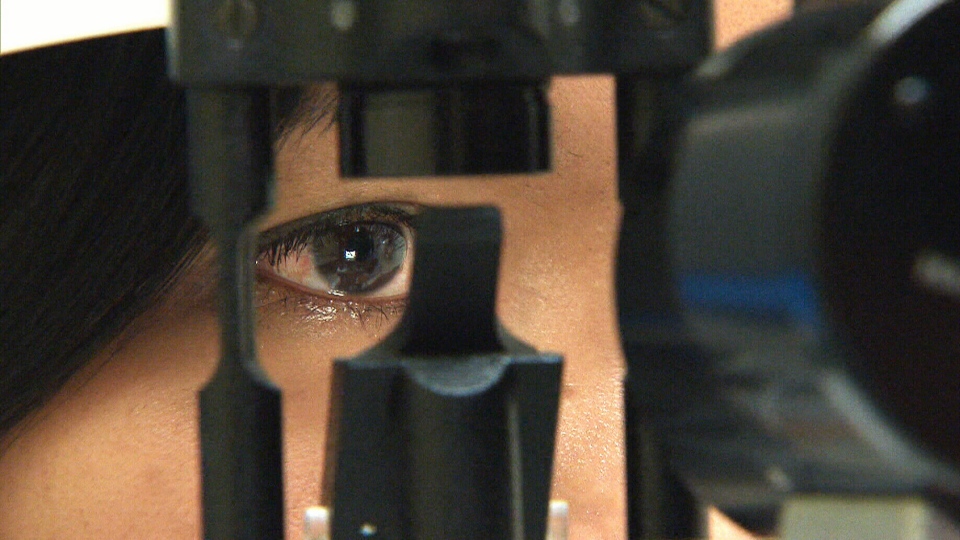

In August of 2020, D’Andrea had a routine appointment with her eye doctor, who had been aware that she’d been experiencing this distorted vision.

“She mentioned that the drug Elmiron, because she saw it in my file, could cause some of these symptoms,” D’Andrea said.

D’Andrea looked up information about the drug as soon as she got out of the appointment. After reading up on it, she decided that same day to stop taking the drug, just in case.

Shop owner Lorean Pritchard, who lives in London, Ont., started taking the drug in 2002. But she went off it in 2015, mainly because it was expensive.

She now blames the drug for her gradual loss of vision.

“I just noticed over time that I wasn’t seeing as clearly as I should have,” Pritchard told CTV News.

She said that signs appeared to be distorted, her eyes were filled with “floaters,” her ability to recognize people was weaker than before, and, worst of all, reading grew more difficult.

“I am a passionate reader, that is my number-one love,” she said.

The biggest impact has been on her vision while driving at night.

“I would see some road signs in advance and I would test myself,” she said. “It was the distortion that cued me that things were not right, even after I had new prescriptions.”

Sometimes when customers are standing right in front of her at her store, she can’t see them clearly, she said.

“It has been very stressful,” she said.

Pritchard worries about the “burden” there will be on her husband if her vision continues to worsen.

“I’m not going to have the freedom to drive, I am not going to have the ability to enjoy my books. It’s going to affect my whole lifestyle,” she said.

Although Elmiron is effective at stopping bladder pain, studies have been increasingly finding that it may be linked to damage in the retina of the eyes.

One study found that about a quarter of people taking Elmiron for five years or more had experienced significant damage to the retina, and identified that more significant exposure to the drug was associated with more severe atrophy.

A study from 2018 found that the retinal damage associated with Elmiron is distinguishable from hereditary damage.

And a recent report warns the changes may progress even after patients stop taking the drug.

Dr. Nieraj Jain, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Emory University School of Medicine, was one of the first to raise alarm bells about Elmiron.

He told CTV News that the damage seen in these patients affects delicate cells that dictate how they process light.

“These cells are called photoreceptors,” Jain said. “They’re light-sensing cells, and the cells underneath those photoreceptors [are] called the retinal pigment epithelium, or RPP.”

“Those cells need to be working well, they need to be in tip-top shape, in order for us to have a very sharp vision that we have. And in patients who have this Elmiron-related maculopathy, we’re seeing disturbances in the pigmentation there, and degeneration or loss of some of those cells.”

He said that some of these changes in the retina could persist long-term, up to 20 years, “and perhaps in some eyes that are more significantly affected … things can worsen down the road.”

Warnings have been issued before. Last year, the Canadian Urological Association Journal published an article about the possible risks for long-term Elmiron users.

In 2019, Canada issued an alert about the drug, adding “the risk of pigmentary maculopathy” — a term that refers to a specific type of vision loss — to the warnings and precautions section for the drug when it is sold in Canada.

And two months ago, Health Canada issued a letter to health-care professionals, providing new information about the potential risks of the medication.

“These changes may be irreversible, and retinal and vision changes may progress even after cessation of therapy,” the letter states.

But Pritchard says the advisories still aren't reaching patients. She only found out about the risks of Elmiron by watching CTV News.

Last spring, CTV News aired a story describing the dilemma many people struggling with painful bladder conditions were grappling with, forced to choose between bladder pain and a drug that could damage their eyesight, according to emerging evidence.

“When I saw the CTV segment, it all made sense to me,” Pritchard said.

“I was relieved because I had answers, but then I was very frustrated. Had I been told way back in 2002 that there was a possibility that my vision would be affected and that I would lose my vision, I probably would not have taken that prescription.”

Both she and D’Andrea have joined a class-action lawsuit against the drug makers, alleging that they did not disclose the risks of the drug sufficiently to the public.

Janssen, the manufacturer of the drug, has said that they will defend themselves and their product against the lawsuit.

“At Janssen, nothing is more important to us than the health and safety of the patients who use our medicines,” they told CTV News in a statement. “ELMIRON® is an oral medicine indicated for the treatment of Interstitial Cystitis, which involves inflammation and irritation of the bladder wall. We work closely with Health Canada to ensure the prescribing information for ELMIRON® appropriately reflects the risks and benefits of the medicine based on the information available to us. We plan to defend against the claims made in this litigation.”

If the class-action lawsuit is successful, the company could have to pay up to $500,000 to each person affected.

D’Andrea said that realizing Elmiron might be behind her vision loss was a “life-changing moment for sure.”

She said she had planned to continue working as an archeologist “for at least another seven or eight years,” but that in light of her vision, she’s having to reconsider her entire life plans.

“In my weaker moments, I do get angry and upset, but for the most part I’m doing my best to try to work around those obstacles,” she said.

In the meantime, the women are urging others on the medications to get regular eye exams at the very least, and to watch for vision changes that could be irreversible.

“In the short run, I think it is very important to get the word out,” D’Andrea said. “People who are taking the drug or thinking of taking the drug should immediately go visit their physician.”