Two class-action lawsuits have been launched by Canadians against the U.S. manufacturer of a device designed to block potentially deadly bloods clots.

The plaintiffs allege the apparatuses have broken apart and become trapped inside their bodies, and left them dealing with the painful consequences.

In August 2013, a Cook Medical inferior vena cava filter was implanted inside Wendy Kopeck of Red Deer, Alta.

The device was supposed to save her from a potential embolism should the blood clot in her leg travel towards her lungs or heart.

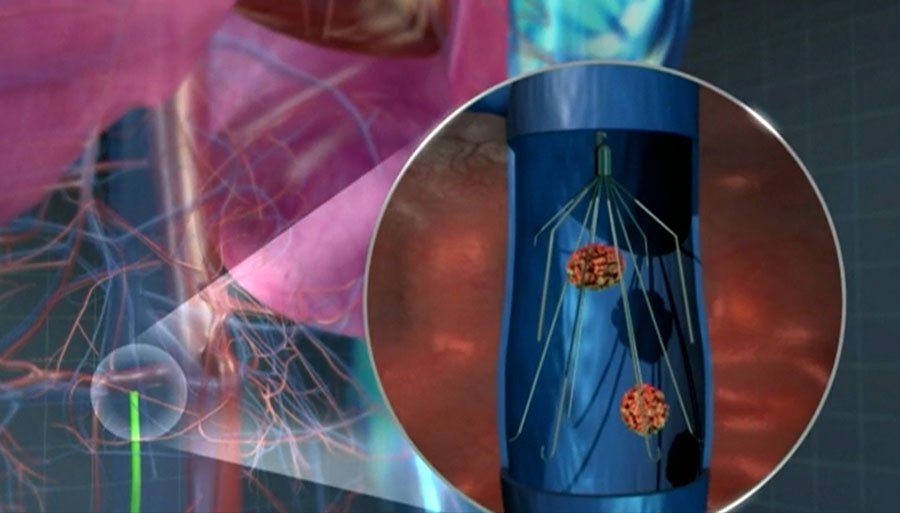

The thin, wire-apparatus is implanted into the inferior vena cava -- which is the largest vein in the body that runs along the spine towards the heart -- and works by capturing a blockage and allowing the blood to flow around it, using the body's natural anticoagulants to break it down. The devices are often used temporarily until a patient can be placed on blood thinners.

But when Kopeck went to have it removed in October, doctors determined it was too risky to proceed. A PET scan a few weeks afterwards revealed the filter had broken, with one leg piercing her internal jugular vein and the rest of the device migrating into her small intestines.

Kopeck says doctors told her it was too dangerous to remove the device and she would have to stay on blood thinners for the rest of her life.

And now, Kopeck is worried the filter is a "ticking time bomb."

"I'm very afraid that someday I may move just the wrong way, or it may just fail on its own, which is what is happening, and the (device's) leg will break and the filter will travel to my heart and kill me," Kopeck told CTV News.

In response to the ordeal, Kopeck and her husband filed a $200-million class-action lawsuit against Cook Medical last month, alleging she was never warned of the potential risks.

"The science is showing there is all sorts of problems with retrieving them. They can break off, migrate, puncture the lungs and cause serious injuries that people are not properly warned of," said Kopeck's lawyer Matthew Baer.

And the Kopecks aren't the only Canadians to launch a lawsuit against the U.S. company.

On Monday, Arie Kuiper of Courtice, Ont., filed a similar lawsuit, asking for $500,000 for each person implanted with a Cook Medical IVC filter, as well as $20 million in damages.

Kuiper says doctors have since made two unsuccessful attempts to remove the device and have been told it is likely they will not be able to extract it. He is scheduled to undergo a third attempt on Monday.

In his claim, Kuiper alleges he has experienced dizzy spells and has been told it’s possible his filter is becoming clogged and is blocking his blood flow.

In a statement sent to CTV News, Cook Medical said "all medical devices and procedures have benefits and risks associated with them."

"Each patient is unique, with different anatomy and risk factors for (pulmonary embolism), that’s why it’s critical for patients and physicians to have a consultation to make sure filters are the right treatment for them," said Moriah Sowders, content specialist for Cook Medical, in the statement.

Lawsuits in the U.S. have been launched against a similar filter, the G2 by Bard, which is also sold in Canada.

In U.S., between 350,000 and 600,000 people each year are affected by blood clots, and as many as 180,000 will die because the blockages travel to their lungs.

In response, doctors have been implanting IVC filters in roughly 250,000 patients across the continent every year to catch these clots before they can do serious damage.

The FDA recommended these retrievable filters be removed within 29 to 54 days.

A 2014 study involving researchers from the University of Ottawa and the Ottawa Hospital Research institute found that IVC filters were "associated with a substantial rate of complications," including those relating to blood clots.

The study looked at 338 patients over a median of more than 16 months. In most patients, the devices were safe and worked as designed, with 20 per cent having one or more “filter-related complications.”

The devices save lives. Without them, blood clots may travel to the lungs and be fatal.

"I think it's important to make sure that we limit the use of the filters only for when patients absolutely need them," said one of the paper's authors, Dr. Lisa Duffett of the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

Another paper published in last September looked at 88 clinical studies and 112 reports, and found the filters had pierced the inferior vena cave in 19 per cent of cases. It concluded caval penetration is "frequent but clinically under-recognized."

Health Canada told CTV News it has received 12 unique incident reports relating to IVC filters by Bard and Cook from Jan. 1, 2008 to February 1, 2016, including: six incidents of perforation or penetration; five of migration; and three relating to an inability or difficulty in removing the devices.

Each incident report “may include more than one reported issue,” the agency said.

It said it has not received any reports of death relating to the devices.

Last December, the society of Interventional Radiologists, Society for Vascular Surgery and blood-clot filter manufacturers also launched a five-year study involving 2,100 patients to look at the safety and effectiveness of the devices. The massive study was also organized with the help of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

One doctor in California has created a clinic that specializes in the removal of these devices. He's been treating Canadian patients as well.

“Every year, we receive hundreds of consultations from around the country and around the world, and our center accepts the most complex cases that cannot be managed elsewhere,” Dr. William Kuo said.

“We are routinely consulted to treat patients from Canada suffering from filter-related complications,” he added.

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip