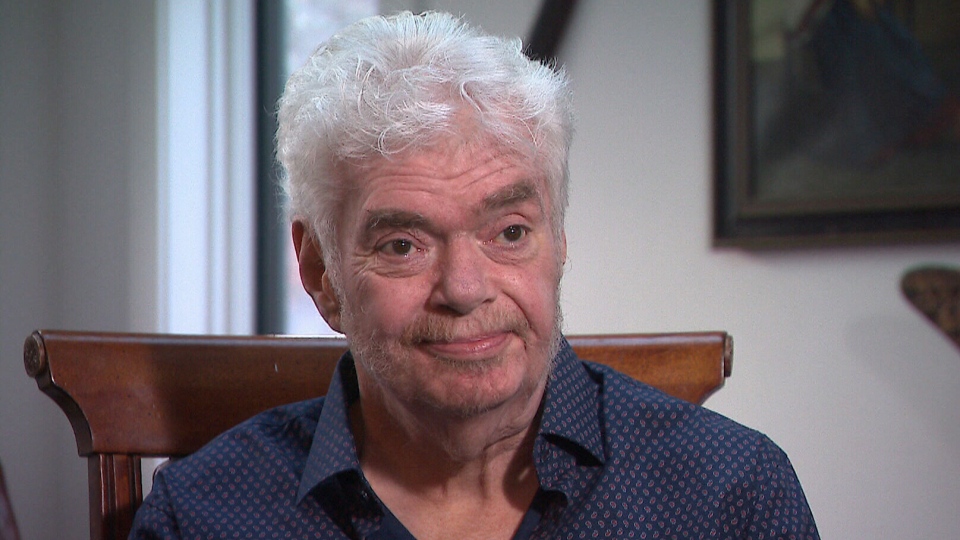

TORONTO -- Like millions of Canadians, Dr. Frank Plummer used alcohol simply to relax after work. Or so he told himself.

Only after he became ill with liver failure was he forced to confront a painful reality: he suffered from alcohol-use disorder.

“I guess I was in denial,” Plummer told CTV News. “It’s pretty obvious now that I look back that I had a problem.”

Plummer had an illustrious career as a physician, researcher and the scientific director of Canada’s National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg. He worked on the front lines of medical crises such as the AIDS epidemic. His groundbreaking work studying HIV/AIDS in Nairobi revealed that the disease did not only affect gay men, as was thought at the time, but could impact heterosexuals and women. He guided Canadian public health through Ebola scares, SARS and the arrival of the pandemic swine flu strain, H1N1, in 2009. As a result of his decades of work the 67 year old has won multiple awards, including the Order of Canada.

But while he was working tirelessly to improve the lives of others, Plummer was also using whiskey -- up to 20 ounces a night -- to deal with the resulting stress.

“I used to think about alcohol all the time,” he said, admitting that part of his brain used to be constantly planning how he’d get more. He thought he was managing it because he never drank on the job.

“I think I was a high-functioning person with a problem with alcohol,” he said.

In 2012, he suddenly became sick: “My belly blew up, and I found I had cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease.”

He was given a liver transplant in 2014. The new organ was “magical,” he said, but the then-retired scientist soon discovered that without “that adrenaline from responding to some pandemic somewhere,” to distract him, he couldn’t stop himself from returning to drinking. And the problem simply became worse and worse from there.

His wife Jo Kennely told CTV News that at first she couldn’t comprehend it.

“I kept on thinking as we went through this, you know, he’s the smartest man in Canada,” she said. “He’ll be able to figure this out, we’ll get through this, he’ll want to survive, he’ll want to stop, he’ll want to do these things.”

Eventually, she realized “it doesn’t matter how smart you are, doesn’t matter how educated you are. It affects everyone. No one is immune from this disease.”

Plummer underwent therapy, alcohol treatment programs, AA meetings. Nothing, he says, worked for long, and he was not a candidate for a second liver.

“If I didn’t get the drinking under control, I was going to die,” Plummer said. “And I didn’t want to die.”

With his options running out, Plummer agreed to be the first person in North America to test an entirely new way of stopping alcohol addiction -- by treating it with deep brain stimulation.

THE TREATMENT

In December of 2018, doctors at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre implanted two electrodes into Plummer’s brain while he was still awake. He was able to talk and answer questions during the surgery.

The electrodes are connected to a device similar to a pacemaker in the upper right side of his chest. It sends electrical impulses deep into the brain to an area called the nucleus accumbens, which is linked to addiction and alcoholism and plays a central role in the brain's reward circuitry.

“So we’re inserting electrodes directly into that region of the brain in an effort to reset its activity, to recalibrate it in some way,” Lipsman said. The device is controlled by an external monitor that Plummer and his doctors can adjust and turn on and off.

The study’s goal, Lipsman says, is to raise awareness of the disease, and to validate the growing awareness that alcohol addiction is likely “a brain-based illness.

“And there should be no better way to treat a brain-based illness than a brain-based intervention.”

According to Lipsman, the pilot study now underway will test six patients like Plummer who have treatment resistant alcohol-use disorder, and for whom all other therapies have failed.

Alcohol addiction is a problem that affects hundreds of thousands of Canadians. According to a report by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, more Canadians were hospitalized in 2017 due to alcohol-related causes than were hospitalized for heart attacks.

It’s also the top cause for hospitalization linked to substance abuse across the entire country, accounting for more than half of hospital stays caused by substance abuse. Ten Canadians die in hospitals per day due to substance abuse -- and three out of four of those deaths are due to alcohol, according to figures from the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

For Plummer, this new trial didn’t just mean a chance to get help for himself, but a chance to contribute to the science aimed at minimizing those deaths.

“I spent my whole life doing research, and here’s a different way of doing research,” he said. “Be a participant, rather than the study director.”

THE IMPACT

A year later, the stimulator is on 24-7 and Plummer reports that he no longer is obsessed with thoughts of drinking.

“It’s given me my life back,” he said.

His wife said that while the treatment may not be a “cure,” it has acted as one for the family as a whole.

“It’s a cure for us,” she said.

Before, she said, the need for alcohol was like “an itch,” that Plummer was compelled to scratch at, and had to address before he could think about anything else, but “now … that itch is gone.

“It’s like night and day.”

Lipsman said that their test trial only sought out subjects whose alcohol addiction had gotten so bad that it was verging on fatal.

“Frank is really a typical example,” he said. “Somebody that has been through a transplant, been through medical treatment and despite that is still affected by his addiction. So those are the kind of patients that we enroll for this particular trial.”

There are risks of infection and bleeding with brain surgery, but so far researchers say the treatment seems to be relatively safe and the first three patients treated are doing well.

“There are encouraging signs that we’re having a meaningful impact on their drinking behavior and on their mood as well,” Lipsman said.

Currently, Sunnybrook is the only centre in the world actively performing deep brain stimulation on patients with treatment-resistant alcohol-use disorder. As the study continues, researchers will also be monitoring changes in brain structures and activity. The study is currently being funded by philanthropic grants, which cover the cost of medical care and follow-up as well as the cost of the equipment. The stimulator alone can run anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000.

Deep brain stimulation is widely used to treat Parkinson’s disease and also depression. It’s also being tested for eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders and Alzheimers. Dr. Lipsman says there may soon be attempts to try DBS as a treatment for other forms of addiction outside of alcohol use disorder.

Plummer is a prime example that addiction can strike anywhere -- it targets not only those who are visibly struggling, but also those who appear to be successful in all avenues of their lives. The misconceptions surrounding who is affected by addiction are just one of the reasons that Plummer says “it’s important to talk about alcohol-use disorder.”

He told CTV News that there is “a stigma,” surrounding the illness.

“Training as a medical doctor, I didn’t think much of people that had problems with alcohol,” he said. “And I never thought of myself like that.”

Although he admitted to judging those who struggled with addiction in the past, he said his experience was eye-opening.

“[Alcohol addiction] will ultimately kill you if you don’t deal with it,” he said. “It just about killed me.” He added that he thought long and hard about taking his story public, but decided to talk about his struggle with alcohol-use disorder, “to try to destigmatize it.”

These days, Plummer, who now lives in Toronto, says he has a new zest for life. He has reconnected with family and -- most importantly -- is diving back into his passion: infectious diseases.

He is preparing to push ahead with an experimental vaccine against HIV infection, and is working on writing a memoir.

“I’m happier than I’ve been in many, many years,” he said.