TORONTO -- In a lab at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, scientists went on a hunt through the DNA of some 10,000 families -- many whom have children with autism.

Through this research, they identified something they call “genetic wrinkles” in DNA itself, a breakthrough they believe could explain why some individuals find themselves on the autistic spectrum.

The hope is that this could be an important new clue into how to diagnose autism spectrum disorder (ASD) early, or even treat it.

Dr. Stephen Scherer, co-author of the study released Monday and director of the Centre for Applied Genomics at SickKids, told CTV News the new discovery is “really quite exciting.”

“It unveils a whole new class of genes that we didn't know (were) involved in autism before,” he said.

“We do know that they're involved in brain function but we don't know how they fit into the jigsaw puzzle.”

Current research estimates that genetic factors should be found in anywhere from 50 to 90 per cent of individuals with ASD.

Scientists already know of about 100 genes that play a role in the development of autism, but these genes only explain less than 20 per cent of cases.

In order to delve further into these genetic components, researchers had to “develop new methodologies,” Scherer said.

Ryan Yuen, the team leader for this new study, rose to the challenge.

Nine years ago, he developed a “new computational approach,” according to Scherer, which allowed him to search for specific characteristics within DNA itself, and compare patterns found within individuals with autism to their parents or “other controls in the population.”

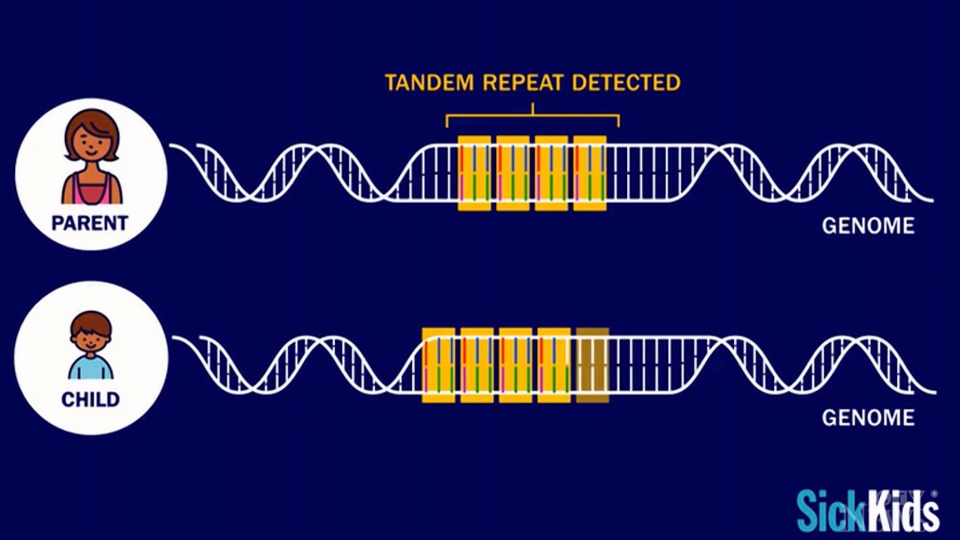

Now they’ve discovered that sections of DNA from parents sometimes get doubled -- or, in some cases, tripled -- in their children.

These are called tandem repeat expansions.

“Tandem repeats are nucleotides, which are the building blocks of DNA, repeated adjacently, two or more times,” Yuen told CTV News. “They're like DNA wrinkles.”

When these wrinkled strands of DNA are replicated, the repeat can grow longer, which is why a tandem repeat present in a parent’s DNA could be expanded from parent to child.

The larger these wrinkles are, the more likely that they could interfere with gene function.

Tandem repeats had been studied before individually, but it was difficult, as they had to be searched for in one gene at a time. Since there can be a million tandem repeats in the genome, according to a press release from SickKids, locating the tandem repeats that actually contribute to ASD “would be like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

“In this study we pioneered a method that can effectively search and analyze terabytes of whole genome sequencing data for tandem repeat expansions,” Yuen told CTV News.

“Many of the genes linked to [these] repeats [were] never thought to be involved in autism before.”

Some of the new genes identified included those “involved in the nervous system,” he said. And the location of the tandem repeat expansion within the DNA itself was associated with “certain characteristics and behaviours such as IQ and life skills,” the press release said.

“This really is a game changer for autism, and genomic research,” Yuen said. “It opens up new opportunities in precision diagnostics and medicine.”

Another way of thinking about these anomalies within the DNA, Scherer said, is as music.

“One of the really interesting findings that was made in this study was there's identified to be about a million different sites across the vast expanse of the human genome that have the ability to expand and also contract,” he said. “These are these repeat regions that we've mentioned.

“And I think the way we think about this is the DNA in these regions is kind of like an accordion. If they stretch out to a certain extent, the music that's played by the DNA or by the instrument has a different tone to it, so the genes are really music here. It’s a different […] song that's played.”

Scherer said that in the almost two decades he’s been studying the autism spectrum, “this is the most exciting advance we've had in 15 years.”

The discovery may lead to improved genetic tests, a boon for families and individuals with autism who want a key question answered: Why?

Yuen believes this research will “impact thousands of families,” and will allow scientists to provide countless individuals with autism a clear explanation for their autism by looking at their genes.

“And all of the individuals with autism can also have serious medical conditions,” he added. “So identifying [these] new tandem repeat expansions to paste into the genome and find out […] the other [genes] involved can provide crucial information for the families and the health care providers.”

Kristen Ellison, who lives in Cobourg, Ontario, is tentatively excited about the study.

Her son, Carter, is nine years old, and on the autism spectrum. He was diagnosed when he was only two years old.

“We're in the infancy of this research and so realistically, I don't know if it's gonna have an impact, right away,” she told CTV News.

“But I hope that one day, these events will have an impact and improve the quality of life for people with autism.”

It’s a hope that Margaret Spoelstra, Executive Director of Autism Ontario, shares.

“[It’s] not only ‘why does my child have this’, but also does this information tell us anything that we might be able to do to support our child, or just support their development, their health, their learning,” she told CTV News.

“I think that is the ultimate goal in this, is to have a greater understanding and a greater way to support, not to eliminate. That's not the goal. For families [it] is really to see how can we help my son, my daughter, my child, be the very best that they can be.”

According to Scherer, looking at the DNA can assist in informing patients and their families early on what type of autism they have, so they can plan for care.

“This new discovery actually adds at least 15 or so new groupings of autism,” Scherer said. “Depending on the type of autism one has, you would see a set of specialty doctors -- neurologists, for example.”

The finding may also help scientists find medication that can target these regions in the DNA itself.

Researchers suspect these genetic wrinkles may play a role in other complex conditions related to the brain -- such as epilepsy and schizophrenia.

“This method also allows other researchers to apply their own data for further genomic discovery,” Yuen said.

Now that scientists have the tools to identify these wrinkles, they can try to find a way to iron them out.

“This is a major scientific advance in the understanding of autism and it will change lives,” Scherer said.

“It may take a little bit of time but we'll get there.”