Adults who have had half of their brain surgically removed in childhood are able to display relatively normal cognitive abilities thanks to the brain’s remarkable ability to rewire itself, according to new research.

For the study, academics from the California Institute of Technology studied the cognitive and sensory and motor functions of six adults who underwent a rare surgery called a hemispherectomy where half of the brain is removed or disconnected from the other hemisphere.

Hemispherectomies are performed in extreme cases of epilepsy where patients have intractable seizures that can threaten the healthy half of the brain or in cases where patients have a neurological disorder that affects only one half of the brain.

The procedure is most commonly performed on children because their developing brains are more flexible or “plastic” than adult brains and they are, therefore, more likely to be able to compensate for the loss of one hemisphere.

In the study, the six adult subjects received their hemispherectomies when they were children, between the ages of three months and 11 years.

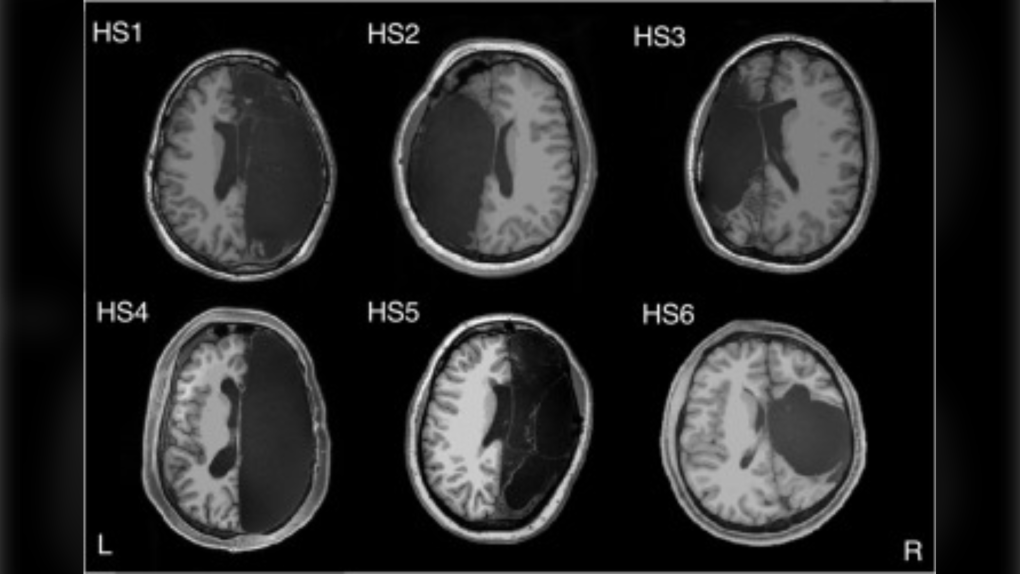

The researchers scanned the brains of the six adults using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology while the patients were in a “resting state,” where they don’t do a specific task during the test. They then compared them to the scans of healthy individuals.

The scans of the patients who had hemispherectomies showed their brain networks, which control walking, talking, and other functions, were surprisingly intact.

“Despite missing an entire brain hemisphere, we found all the same major brain networks that you find in healthy brains with two hemispheres,” lead author Dorit Kliemann, a cognitive neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in a press release on Tuesday.

What’s more, the researchers discovered there were actually more connections between the brain networks in patients who had hemispherectomies than in those of healthy subjects.

For example, the scholars said the regions in the patients’ brains that control walking appeared to be communicating more frequently with the regions that control talking than in ordinary brains.

“It appears that the networks are collaborating more,” Kliemann said. “The networks themselves do not look abnormal in these patients, but the level of connections between the networks is increased in all six patients.”

While most brains use both hemispheres to function, the researchers said their study shows that brains can adapt by strengthening the existing networks in the remaining half.

Future research

Because the researchers only examined the subjects’ brains in a resting state, they weren’t able to study how the compensation in their brain directly influences their behaviour.

“What happens when there is a specific task or stimulus, such as touch on the left or the right hand?” Lynn Paul, a senior research scientist and principal investigator at the California Institute of Technology, questioned.

“Left touch on the right side of the brain would normally be represented in the opposite hemisphere, for example. But that can’t work if you have only one hemisphere, and so there must be major reorganization of such functions,” Ralph Adolphs, the director of the California Institute of Technology’s Brain Imaging Center, added.

The academics said they plan to study how this might be explained in hemispherectomy patients in the future.

The research was published in the journal Cell Reports on Tuesday. It was made possible by funding from The Brain Recovery Project: Childhood Epilepsy Surgery Foundation, an organization started by the parents of a child who underwent a hemispherectomy.

Paul said she hopes their research will help families make more informed decisions about surgeries and recoveries.

“We hope that a better understanding of how the brain is compensating in people who have optimal outcomes will eventually inform targeted intervention strategies for future hemispherectomy patients,” she said.

Kliemann said they want to continue studying the brains of children before and after they receive hemispherectomies to see how they develop over time.

“Yes, they have challenges, but their cognitive abilities are still remarkably high functioning given that they are missing half of the brain tissue,” she said. “We need to understand how this is possible with only a single brain hemisphere—an important question about plasticity, reorganization, and compensation.”