The North Korean nuclear threat against the continental U.S. poses some problems for Canada, especially if the North Koreans fail to perfect their aiming technology.

Kim Jong Un’s regime now claims to have the capability to strike anywhere within the continental United States after the Nov. 28 test of its latest missile, dubbed Hwasong-15. North Korea claims the missile flew 950 kilometres and reached a height of 4,475 kilometres in a 53-minute flight time.

Experts say those numbers are consistent with their own data, and that the missile could indeed strike at North America. However, some questions remain around whether the test missile was carrying the equivalent weight of a nuclear warhead, or whether it’s actually capable of delivering such a payload.

North Korea claims it can launch a missile at any target in the continental U.S., and has allegedly figured out how to miniaturize a hydrogen bomb for use on a missile. However, those are just two elements of a highly complex engineering challenge that the North has yet to perfect.

Here are four challenges North Korea needs to master before it can strike North America – and why it poses a threat to Canada.

1. Mastering the art of launching a missile

This July 4, 2017 file photo distributed by the North Korean government shows what was said to be the launch of a Hwasong-14 intercontinental ballistic missile, ICBM, in North Korea. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP)

To match the capability of nuclear superpowers to deliver nuclear payloads from one side of the Earth to the other, North Korea has been working on its own Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) technology. That technology inched ahead slowly for years, but experts say it’s suddenly accelerated in 2017.

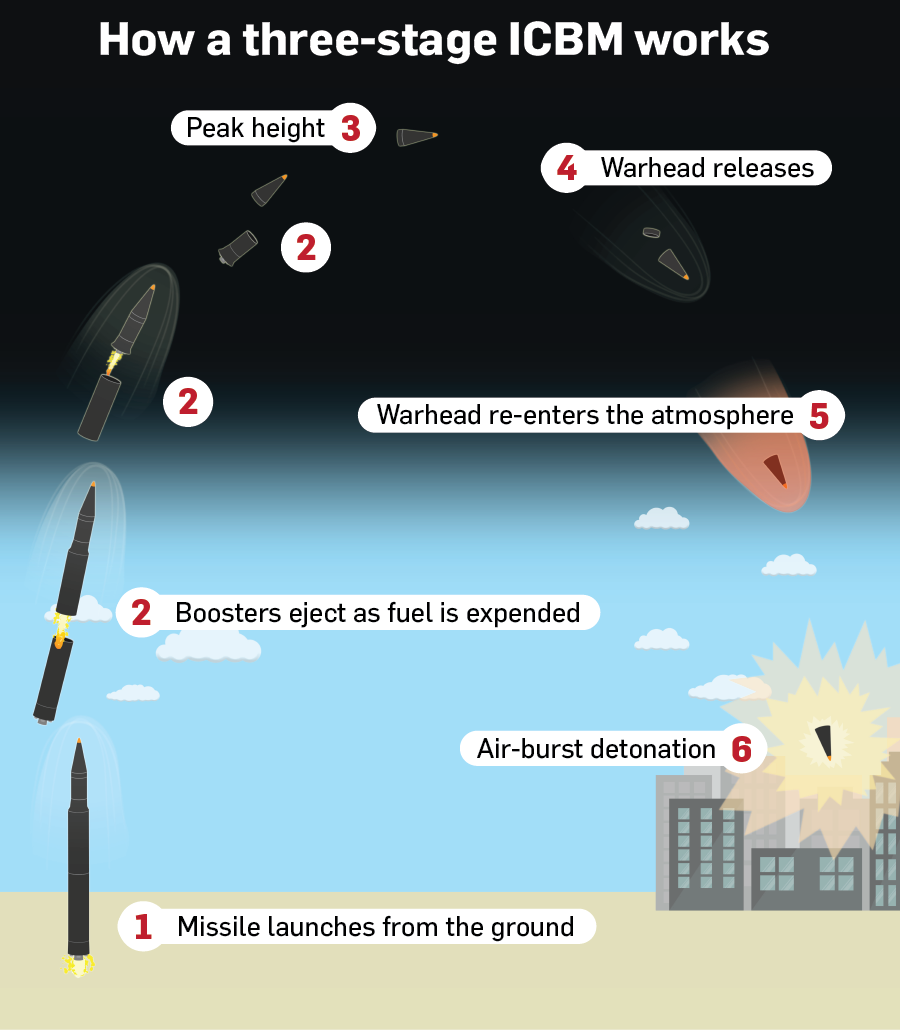

An ICBM works much like the old Saturn V rocket that carried American astronauts into space, using a series of boosters to propel the payload-topped missile, ejecting one booster at a time as the fuel is expended. Most ICBMs, including the U.S. Minuteman III design, involve three booster stages to reach their peak, where only the missile’s nose cone remains, which can be rotated toward Earth to deploy one or more nuclear warheads.

In order for a North Korea missile to successfully strike a target across the Pacific Ocean, for example, its missiles must be capable of reliably executing every stage of that process. North Korea has spooked many observers with its long-range missile tests, but experts say they still haven’t seen proof that the North can pull off every stage of an ICBM attack.

Experts say North Korea likely has the capacity to launch a missile as far as the U.S. mainland or Canada, after advancing its missile program by leaps and bounds over the last year.

The North demonstrated that capacity on Nov. 28 with the test launch of its latest rocket, the Hwasong-15. The rocket was launched in an extremely high arc, but observers say the test indicates North Korea could indeed strike at targets on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. The launch was the first test in 74 days for North Korea.

The North tested two of its Hwasong-14 ICBM missiles in July, and announced after the second test that the “entire” continental U.S. was now in range. Then, in late August, North Korea’s news agency released photos of Kim Jong Un inspecting two new missile designs, dubbed the Hwasong-13 and the Pukguksong-3. The Hwasong-13 appears to be a three-stage ICBM, while the Pukguksong-3 seems to be a submarine-launched ballistic missile, according to observers.

Photos of the missile plans were taken while Kim Jong Un was touring a facility that produces solid-state fuel – a more efficient fuel alternative to liquid fuel when launching long-distance missiles. That, too, would improve the effectiveness of North Korea’s ICBMs.

In this undated image distributed on Sunday, Sept. 3, 2017, by the North Korean government, shows North Korean leader Kim Jong Un at an undisclosed location. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP)

“They continue to improve, whether a particular test fails or not,” Elliot Tepper, an emeritus professor of political science at Carleton University, told CTVNews.ca. Tepper says the North has dedicated tremendous resources to arming itself with nuclear weapons, even at the expense of starving some of its population and drawing harsh sanctions from the international community.

“Every time the West or analysts take comfort that a particular test fails or does not achieve its full potential, it’s overlooked that the North Koreans will just keep trying,” he said.

2. Hitting the right target

North Korea’s ICBM program is still in its infancy, and experts say they probably haven’t figured out how to accurately aim one of their missiles over a long distance. That means a missile meant for the United States could potentially miss and hit Canada, with devastating consequences.

“Don’t trust the accuracy of that technology,” Christian Leuprecht, an RMC political science professor and Macdonald Laurier Institute senior fellow, told CTVNews.ca. “They might aim for San Francisco but the missile might land in Vancouver.”

Leuprecht points out that Canada has no missile defences against incoming ICBMs. Instead, Canada could hope the U.S. would use deploy its missile defences, despite Canada’s 2005 announcement it would not participate in the American ballistic missile defence program.

“There’s currently no authorities for NORAD, through the ballistic missile defence shield, to engage (an ICBM),” Leuprecht said.

Canada's Lt.-Gen. Pierre St-Amand, deputy commander at the Colorado-based NORAD, made that policy clear at a House of Commons defence committee meeting on Sept. 14.

"We're being told in Colorado Springs that the extant U.S. policy is not to defend Canada,"he said.

Nevertheless, UBC political science professor Allen Sens suggests Canadians shouldn’t be scared at this point, because it’s unlikely North Korea’s capabilities can live up to their claims.

“They have every incentive to distort their real capacity,” he told CTVNews.ca. “A lot has to happen before we start promoting that kind of fear-based dialogue.”

In this April 15, 2017, file photo, an unidentified missile that analysts believe could be the North Korean Hwasong 12 is paraded in Kim Il Sung Square in Pyongyang, North Korea. (AP / Wong Maye-E)

Sens expects that the U.S. would try to shoot down an incoming ICBM anyway, because of the difficulty determining exactly where it’s aimed at, and the fact the U.S. also doesn’t want to see Canada hit by a nuclear weapon, “because the Americans would be impacted.”

3. Delivering a miniaturized nuclear warhead

Even if North Korea could effectively aim and launch an ICBM at a North American target, the country still needs to master the complex task of miniaturizing a nuclear warhead that will detonate over its target. Not only are those nukes complex, but their considerable weight is also a factor in how far a North Korean missile can fly. Their Nov. 28 test, for instance, may not have accounted for the weight of such a warhead, experts say.

North Korea has been developing nuclear weapons since 1965, and claims to have detonated six nuclear bombs (five atomic and one hydrogen) in underground tests since 2006. However, observers say their technology has improved much faster than expected in recent years.

Kim Jong Un’s regime trumpeted a major achievement in early September, announcing it had miniaturized a hydrogen bomb capable of fitting onto an ICBM. They also claimed their first successful hydrogen bomb test, which was said to be significantly more powerful than the North’s previous five atomic bomb tests.

The latest test reportedly caused a magnitude 6.3 earthquake, according to observers in South Korea. Experts say it will take time to determine whether it was actually a hydrogen bomb explosion, but regardless, it was the largest quake yet recorded during a North Korean weapons test. Experts say the quake hints at a bomb with the potential yield of 70-100 kilotons, or 70,000-100,000 tons of TNT.

That would make it up to 10 times more powerful than North Korea’s second-most powerful suspected nuclear detonation, and up to five times more powerful than the 21 kt and 15 kt atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945.

But nuclear arms analyst James McKeon cautions that the precise nature of the latest North Korean test remains unverified.

“If it truly is a hydrogen bomb… it would be a major development,” McKeon, of the Center for Arms Control and Non-proliferation, told CTV News Channel.

If an atomic bomb is like an exploding hand grenade, then a hydrogen bomb is like a hand grenade exploding on a pile of dynamite.

A hydrogen bomb is best-understood as a two-stage bomb, splitting atoms apart, then using that power to combine atoms for an even larger explosion. Atomic bombs only accomplish the atom-splitting part of that reaction, and so are not nearly as powerful.

McKeon says building a hydrogen bomb is key to producing an ICBM-ready a nuclear warhead, since it’s lighter and more powerful than an atomic bomb.

“If they’re able to miniaturize this warhead, and if they’re able to make it light enough to be able to put onto a ballistic missile, that means they have the full capability to strike targets virtually anywhere on Earth,” he said.

But no matter how powerful the North Korean bombs might be, experts suggest that the more difficult engineering challenge may actually be keeping their warheads intact as they re-enter the atmosphere.

4. Surviving re-entry

The same atmosphere that protects Earth’s surface from space debris is a major obstacle when it comes to rocket science, because a missile’s payload – or a spacecraft – can burn up as they re-enter the atmosphere from space.

Long-distance missiles need to leave the atmosphere to reach distant targets, but their payloads also need to be able to smoothly re-enter the atmosphere before that can strike a target.

Tepper says re-entry is the biggest remaining obstacle for North Korea’s fledgling rocket program.

“They have to find a way to shield that nuclear-tipped ICBM from catching on fire as it re-enters the atmosphere,” Tepper said. “That’s a major step, and it’s not easy to achieve.”

The United States solves the problem by ejecting the nose cone off the top of its Minuteman III missile before deploying cone-shaped warheads that can survive the atmospheric re-entry.

But North Korea appears to be taking a different approach, judging from images of their weapons that have been studied by U.S. experts. Those images suggest the North is trying to deliver a single nuclear warhead housed inside the missile’s nose cone, which could perhaps be coated with a material to help it survive re-entry. Images of one such delivery device were revealed with the announcement of North Korea’s H-bomb test in early September.

This undated image distributed on Sunday, Sept. 3, 2017, shows North Korean leader Kim Jong Un inspecting a supposed hydrogen bomb, with plans for a nuclear warhead shown in the background, at an undisclosed location in North Korea. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP)

Sens says North Korea also needs to master the moment when the warhead is ejected from the missile for its final descent. The missile might be travelling at the speed of sound at this point, making it technically difficult to shoot something out the end of it at an even faster speed.

“It’s not easy to push a warhead out of a missile in flight,” he said.

Re-entry likely remains a challenge for the North Koreans, but as Tepper points out, it wouldn’t stop the North from striking at its neighbours in Japan or South Korea. Those targets are much closer, and could be hit with a short- or medium-range missile that doesn’t need to leave the atmosphere to hit its target.

“What is at the moment a distant and hypothetical threat for Canada… is, for the immediate neighbours in South Korea and Japan, an imminent existential threat,” he said.

This Aug. 29, 2017 file photo distributed on Aug. 30, 2017, by the North Korean government shows what was said to be the test launch of a Hwasong-12 intermediate range missile in Pyongyang, North Korea. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP)

This story is part of a three-part series on the nuclear threat North Korea poses to Canada.