In high school, Mariko Shimoda knew she liked science and math but wasn’t sure what program to apply for in university.

In eleventh grade, she spent a weekend with about 50 other girls at the University of Waterloo, in Waterloo, Ont. The outreach event featured speeches from successful female engineers, a tour of Google’s local office and a workshop where the girls took apart an engine.

Mariko Shimoda (right) University of Waterloo

Shimoda had never tinkered with her dad’s car and had opted for student’s council over robotics club, so the engine dissection gave her a needed jolt of confidence. For the first time, she says, “I could see myself actually working with that kind of stuff.”

Now, in her second year of mechanical engineering, Shimoda feels she made the right choice.

But there were times when she felt like she might not belong. For example, it was shocking to see a relatively recent mechanical engineering graduation class photo with only a handful of female faces staring back.

It was also an awkward feeling when she found out that she was the only female engineer on the team during her co-op term at a software firm.

RELATED: Killam Prize winner Molly Shoichet's 5 ideas to get more women in STEM

Then there was the time she announced she had lined up three interviews for co-op jobs and a male colleague scoffed that it was only due to “diversity quotas.”

The truth is, despite decades of campaigns to get more women into engineering, female engineers still face a world where they’re forced to face questions about whether they fit in.

The latest high-profile reminder was the controversial firing of Google engineer James Damore, who argued in an internal memo that the gender gap can be explained by “biological differences,” including research that shows men are more than interested in “systematizing,” less “extroverted” and less “neurotic” than women.

Gender equality advocates argue that, in fact, women are just as good at science, technology, engineering or math; they simply face stereotypes that keep them from choosing it. They point to research like a Statistics Canada study that looked at highly respected Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores and found that only 23 per cent of Canadian females with high scores in math at age 15 chose STEM, compared to 46 per cent of high-scoring males.

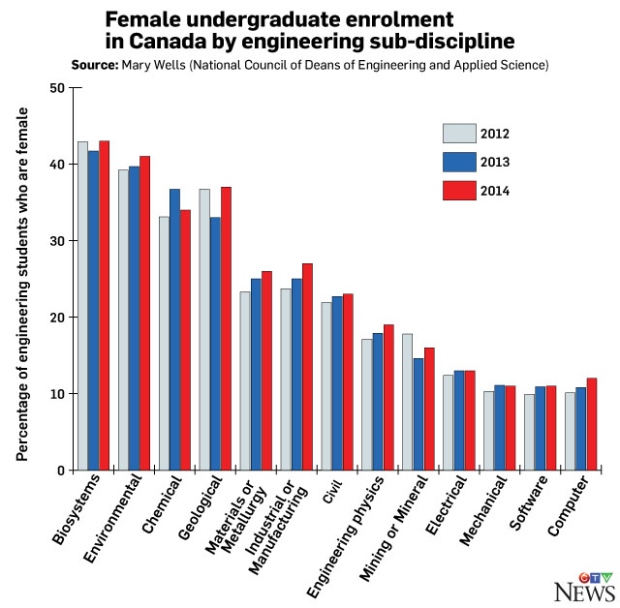

Whatever the explanation, the number of women in Canadian engineering programs has barely budged in the past decade and a half. Figures from Engineers Canada show that undergraduate engineering programs were 20.3 per cent female in 2000. Fifteen years later, in 2015, the figure had dropped slightly, to 20.1 per cent.

The imbalance is, naturally, reflected in the workplace. Only 13 per cent of practicing licensed engineers were female in 2015. Among the newly licensed, it was 17 per cent.

Universities are asking what more they can do.

Waterloo's new option

One new approach that’s grabbing attention online is new Women in Engineering Living-Learning Community (LLC) launching this fall the University of Waterloo, where about 500 out of 1,700 first-year students are expected to be female. About 50 of the women starting Waterloo engineering will live together in this optional women-only residence, which is made up of clusters of females inside a mixed-gender building.

The idea is to create an environment where women can support each other with everything from coding skills they might have missed in high school to dealing with sexist remarks.

The women will be supported by paid older students called “peer leaders,” who will run special activities designed to prepare them for the sexism they may face in the working world. They will, of course, take the same classes as male students.

Not everyone likes the idea. Many people have posted critical comments about the LLC on Waterloo’s Reddit page, though few seem willing to discuss it publicly, citing fear of repercussions from classmates or employers.

Waterloo Master of Science student Uma Lad is among those willing to go on record. She told CTVNews.ca that she worries the residence will only reinforce stereotypes that women can’t do science or math.

But Waterloo Associate Dean of Outreach Mary Wells, who came up with the program, says it’s worth a try because decades of outreach programs haven’t closed the gap. After all, women are still outnumbered in Waterloo’s lecture halls by about two to one, and even more so in programs such as computer engineering, where only about one in six are female.

Graphic by Nick Kirmse / CTVNews.ca

Wells says that’s a problem because without more women in engineering everything from smartphone applications to car air bags may be biased against them.

It’s also hard to close the gender wage gap if women aren’t pursuing what is among the most highly-paid careers. Statistics Canada reports that the mean age-adjusted earnings for a woman with a mechanical engineering degree was $86,549 in 2010, while the mean for women with bachelor degrees overall was $64,420.

Wells says the problem starts when girls form opinions that they’re not good at science and math, making them less likely than boys to take the prerequisites for engineering, particularly Grade 12 physics.

Even if they do end up in engineering school, they face sexism. For example, Wells has seen men lash out at women who get highly sought co-op jobs.

“He cannot imagine that she may be equally as good as he is technically and may have interviewed better than him,” she says. “When the woman hears this, it also reinforces her own view that perhaps she was the diversity hire and that doesn’t make you feel very good,” she adds.

Wells says she hopes the Living Learning Community will offer women a ready-made network of support, which will help them cope with sexism in the workplace. It will also be an easy place for the school to offer speeches from female role models or career-related seminars.

Mary Wells, University of Waterloo

Shimoda, who has been hired to work as a peer mentor in the LLC, says she believes the residence will build on Waterloo’s existing support systems for women, like Whine Wednesday -- weekly gatherings where women openly discuss some of the barriers they face while also picking up skills that they may have missed in high school because of gender biases, like soldering and computer programming.

Shimoda found the discussion on what to wear to job interviews particularly helpful.

“Guys just put on a suit and tie,” Shimoda says. “With girls it’s … do I wear pants or is that too bossy looking? Do I wear a dress or is that too feminine looking? … How long should my dress be? … Do I wear heels? Do I wear makeup?”

Addressing impostor syndrome

She also learned about “impostor syndrome.”

“A lot of people coming into university, but especially females going into male-dominated programs, tend to struggle with impostor syndrome,” she explains. “You feel basically like you’re an imposter and it’s only a matter of time before somebody catches you and throws you out.”

In reality, few women are thrown out of engineering school. Engineers Canada data shows men and women graduate at equal rates. But they are more likely than men to exit the profession within a few years of graduation.

Workplace barriers hurt enrolment

Marcia Friesen, an associate dean of engineering at the University of Manitoba, has been working to boost the number of women in engineering at her institution. Thanks in part to outreach programs, the numbers have improved, but only from 14 per cent in 2009 to 20 per cent in 2015.

Friesen says that not only do women face discrimination in the workplace that causes them to leave the industry, but they tell “horror stories” that discourage some girls from applying.

While she calls it an “extreme example,” Friesen says that men at a local engineering firm recently organized an after-work golf outing and didn’t invite any female colleagues. That’s not only offensive, but it keeps women out of informal networks that can advance people’s careers, she says.

Marcia Friesen talks about workplace culture and diversity (Association of Consulting Engineering Companies Manitoba / YouTube)

Other barriers are less subtle. They may include bosses who don’t understand that mothers are often forced to stay at home with sick children or more likely to take career-interrupting maternity leaves.

In that sense, there’s only so much that universities can do.

Friesen says the University of Manitoba has considered building a special women’s lounge in the engineering school, but female students turned them down, saying they would feel more singled-out.

“Women already feel that they stand out by virtue of numbers and don’t want to do anything to exacerbate that,” she says.

She will be watching Waterloo’s experiment closely.