Cuban government apologizes to Montreal-area family after delivering wrong body

Cuba's foreign affairs minister has apologized to a Montreal-area family after they were sent the wrong body following the death of a loved one.

This image released by Apple TV+ shows, from left, Imani Pullum, Will Smith, Jeremiah Friedlander, Landon Chase Dubois, Charmaine Bingwa and Jordyn McIntosh in a scene from "Emancipation." (Quantrell Colbert/Apple TV+ via AP)

This image released by Apple TV+ shows, from left, Imani Pullum, Will Smith, Jeremiah Friedlander, Landon Chase Dubois, Charmaine Bingwa and Jordyn McIntosh in a scene from "Emancipation." (Quantrell Colbert/Apple TV+ via AP)

The influence of one of the most infamous photos from the American Civil War is still felt today, 159 years later. The picture, taken by the Union Army, of Gordon, a formerly enslaved man known as “Whipped Peter,” display his scourged bare back, the result of brutal whippings.

The indelible image, commonly called The Scourged Back, provided incontrovertible proof of the cruelty of American slavery and helped fuel the abolitionist movement. Now, courtesy of director Antoine Fuqua and his film “Emancipation,” now streaming on Apple TV+, the story behind the photograph is being told. “We are going to make sure that every person in the world truly knows what slavery looks like,” said the photographer who took the picture.

Will Smith, in his first role since the slap heard ‘round the world, is Peter, a deeply religious Haitian slave torn from his wife Dodienne (Charmaine Bingwa) and children to be sold to a Confederate labour camp. Unable to remain silent when the camp’s overseers, like the sadistic Fassel (Ben Foster), abuse the enslaved men working to his left and right, he is labelled defiant and regularly beaten or threatened with a loaded gun to his head.

“They break the bones in my body more times than I can count,” he says later, “but they never break me.”

When Peter learns of the Emancipation Proclamation, signaling that President Lincoln has freed the slaves, he plans an escape, fleeing with a group of men through some of Louisiana’s most treacherous swamps. Driven toward freedom, and the possibility of being reunited with his family, Peter battles nature, and beasts, both the four-legged and two-legged kind, to survive.

Shot in daguerreotype black and white, resembling a high contrast tin type photograph, “Emancipation” looks like a historical document of a sort, but comes with a modern storytelling sensibility. It is both a brutal representation of the evils of slavery and a Will Smith action movie.

As Peter makes his way through the bayou, rubbing onion on his clothes to put the bloodhounds off his scent, battling an alligator or defending himself with a cross-shaped necklace, his journey is rife with danger. The tense action scenes, which make up the bulk of the movie, are well-realized by director Fuqua, but they come at the expense of the character.

We come to understand that Peter is a smart, courageous and resourceful man whose deeply held religious beliefs have given him a roadmap for life, but the film appears more interested in the way he sidesteps danger rather than creating a fully-formed portrait of the man himself.

Smith is raw in his performance and Peter’s inspirational journey to family and freedom is a visceral one, but, as presented, not a deep one.

For better and for worse we know what to expect from a Will Smith hero’s journey film and “Emancipation,” for better and for worse, is just that. It folds a death-defying action movie around a vivid portrait of the scourge of slavery and it’s an uneasy balance. On one side, the film is propped up by Fuqua’s deft, propulsive handling of the action. On the other, it feels like a missed opportunity to dig deep into what made Peter tick.

This image released by Netflix shows Gepetto, voiced by David Bradley, left, and Pinocchio, voiced by Gregory Mann, in a scene from "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio." (Netflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows Gepetto, voiced by David Bradley, left, and Pinocchio, voiced by Gregory Mann, in a scene from "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio." (Netflix via AP)

“Pinocchio,” the wooden boy with a lie detector for a nose and dreams of becoming a real boy bouncing around his sawdusty brain, is one of the most reimagined characters in children's literature. Earlier this year Tom Hanks starred in a traditional remake of the 138 year-old-story that echoed the classic Disney film.

The Oscar winning director of “The Shape of Water” takes the story in his own direction in “Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio,” a stop motion retelling, now playing in theatres and coming soon to Netflix. In what may be the only version of the story featuring a cameo by Mussolini, the movie travels a different, darker path than previous adaptations.

Del Toro keeps the original story’s Italian location, but places the action between World Wars I and II. Woodworker Geppetto (voiced by David Bradley) is a skilled artisan, lovingly teaching his young son Carlo the ropes of the craft while working on large crucifix at a local church. When Carlo is killed in a bombing raid, Geppetto spirals into despair and alcoholism.

While soothing his loss with booze, the heartbroken Geppetto cuts down an Italian pine tree near his late son’s grave and builds a roughhewn puppet as a replacement for his boy. Gangly, with a long nose, the puppet sits slumped in Geppetto’s workshop until a magical Wood Sprite (voice of Tilda Swinton) breathes life into him and appoints Sebastian J. Cricket (voice of Ewan McGregor), a mustachioed insect who lives inside the puppet, as his guide and conscience.

The rowdy newborn, dubbed Pinocchio (voice of Gregory Mann), doesn’t make a great first impression on Geppetto or the local townsfolk. But as Geppetto warms to him, the locals, including fascist government official Podestà (Ron Perlman), don’t quite know what to make of him.

“Everybody likes him,” says Pinocchio, pointing to the still under construction crucifix. “He’s made of wood too. Why do they like him and not me?”

As Pinocchio tries to figure out his place in the world, he soon discovers that not everyone has his best interests in mind.

This is not your parent’s “Pinocchio.” Del Toro sticks to the bones of author Carlo Collodi’s original plot, but expands the story with a deep dive into what it means to be human, mortality, the weight of expectation and the horrors of fascism. It doesn’t sound particularly family friendly, but while there are some intense, nightmarish images, this is a fairy tale in the Brothers Grimm tradition. It speaks to the issues surrounding growing up, whether you’re made of wood or flesh and blood, and should be fine for kids ten and up.

Visually spectacular, the stop motion animation gives the movie a more organic feel than it may have had if rendered in computer generated images. Rich in detail and imagination, the film’s style mixes and matches dreams with nightmares to create a palette that paints the fanciful and the earthbound in equal measure.

“Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio” does something remarkable. Just as the Wood Sprite breathed new life into Geppetto’s puppet, Del Toro breathes new life into a very familiar and often-told story. He is buoyed by fine voice work and visuals, but it is the auteur’s allegorical stamp that really brings this wooden boy to life.

This image released by 20th Century Studios shows Olivia Colman in a scene from "Empire of Light." (Searchlight Pictures via AP)

This image released by 20th Century Studios shows Olivia Colman in a scene from "Empire of Light." (Searchlight Pictures via AP)

“Empire of Light,” a new drama from director Sam Mendes, takes almost two hours to deliver the same magic-of-the-movies message Nicole Kidman’s AMC advertisement drove home in just one minute and one second.

Set in 1981, Olivia Colman plays Hilary Small, a lonely duty manager at a Margate cinema called The Empire. She is fastidious, detail oriented and on top of every little thing, even if she doesn’t really care for the movies she shows in their beautiful Art Deco auditoriums. “They’re for the customers,” she says.

Her personal life is as messy as her work life is ordered. An illicit affair with her boss, Mr. Ellis (Colin Firth), the theatre’s general manager, is a study in power imbalance and an unnamed mental illness leaves her unable to sleep and reliant on lithium to maintain equilibrium.

Stephen (Micheal Ward), a new theatre employee, fits in perfectly with the others, Neil (Tom Brooke), punk rocker Janine (Hannah Onslow) and projectionist Norman (Toby Jones) but really sparks with Hilary, even though she is many years his senior.

At the theatre romance blossoms between them, but in the outside world the rise of the National Front troubles Stephen, and he is regularly harassed by skinheads simply because he is a Black man living in Britain.

As Mr. Ellis prepares to host the regional gala premier of “Chariots of Fire,” events conspire to change the nature of Hilary and Stephen’s relationship, and perhaps the rest of their lives.

“Empire of Light” takes on a lot but does not seamlessly blend its many ideas into a whole. A study of racism, mental illness, power structures and the transformative power of the movies, it is splintered into too many pieces to work as a cohesive story. When Mendes focusses his camera on Hilary and Stephen the movie finds its power, when he does not, it drifts.

Colman, in the film’s most demanding role, once again proves her remarkable ability to inhabit a character. Hilary is a complex person, and as her depression grips, she boards an emotional rollercoaster. Colman carefully and sensitively portrays that aspect of Hilary’s life in a terrific performance, filled with humanity and sympathy.

Opposite Colman in the film’s best scenes is Ward. As Stephen, in a career making performance, he brings empathy to the film. In one of his early moments, he helps a pigeon with a broken wing. That action could have served as an overworked metaphor, given his budding relationship with the damaged Hilary, but instead establishes Stephen’s innate decency in a world that does not always return the favor. Conversely, Ward’s steeliness comes through in several scenes of outrageous racism.

At its heart “Empire of Light” is a love letter to film and grand old movie palaces like The Empire. But once again, Mendes uses the metaphors like a jackhammer on concrete. In an impassioned speech, Toby Jones, who calls the theatre’s projectors his “babies,” explains the magic of the movies to Stephen. “Still images with darkness in between,” he says. “If I run them at 24 frames a second, you don’t see the darkness.” Jones delivers the line with breathless reverence, as if the idea that film as a panacea for all that ails us was something new instead of a clunky metaphor. The “Cinema Paradiso-esque” veneration is well intended, but, given the film’s essaying of racism and mental illness, feels overstated and trite.

Cuba's foreign affairs minister has apologized to a Montreal-area family after they were sent the wrong body following the death of a loved one.

The federal government's proposed change to capital gains taxation is expected to increase taxes on investments and mainly affect wealthy Canadians and businesses. Here's what you need to know about the move.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is accusing Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre of welcoming 'the support of conspiracy theorists and extremists,' after the Conservative leader was photographed meeting with protesters, which his office has defended.

"It's a bit of a complicated pattern; we've got a lot going on," said Jennifer Smith of the Meteorological Service of Canada in an interview with CTVNews.ca on Wednesday. "[As is] typical with weather, all of these things are related."

On a night she should have been mourning, a nurse from Quebec's Laurentians region says she was forced to clean up her husband after he died at a hospital in Montreal.

Police tangled with student demonstrators in Texas and California while new encampments sprouted Wednesday at Harvard and other colleges as school leaders sought ways to defuse a growing wave of pro-Palestinian protests.

Members of the Bank of Canada's governing council were split on how long the central bank should wait before it starts cutting interest rates when they met earlier this month.

A North Bay, Ont., lawyer who abandoned 15 clients – many of them child protection cases – has lost his licence to practise law.

A Winnipeg man said a single date gone wrong led to years of criminal harassment, false arrests, stress and depression.

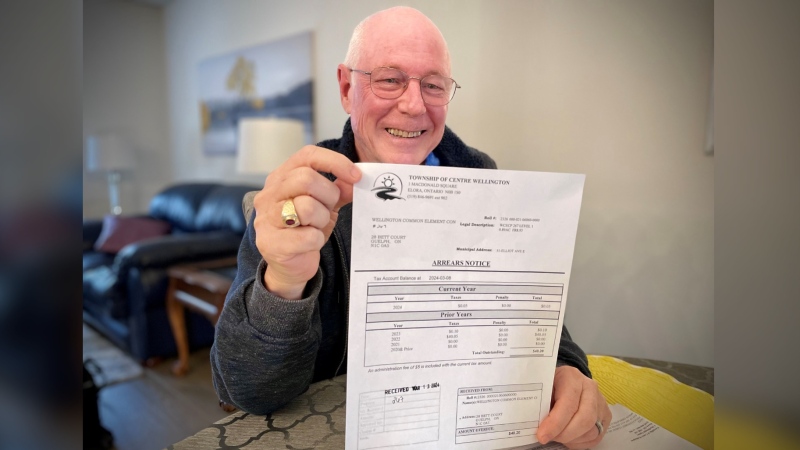

A property tax bill is perplexing a small townhouse community in Fergus, Ont.

When identical twin sisters Kim and Michelle Krezonoski were invited to compete against some of the world’s most elite female runners at last week’s Boston Marathon, they were in disbelief.

The giant stone statues guarding the Lions Gate Bridge have been dressed in custom Vancouver Canucks jerseys as the NHL playoffs get underway.

A local Oilers fan is hoping to see his team cut through the postseason, so he can cut his hair.

A family from Laval, Que. is looking for answers... and their father's body. He died on vacation in Cuba and authorities sent someone else's body back to Canada.

A former educational assistant is calling attention to the rising violence in Alberta's classrooms.

The federal government says its plan to increase taxes on capital gains is aimed at wealthy Canadians to achieve “tax fairness.”

At 6'8" and 350 pounds, there is nothing typical about UBC offensive lineman Giovanni Manu, who was born in Tonga and went to high school in Pitt Meadows.

Kevin the cat has been reunited with his family after enduring a harrowing three-day ordeal while lost at Toronto Pearson International Airport earlier this week.