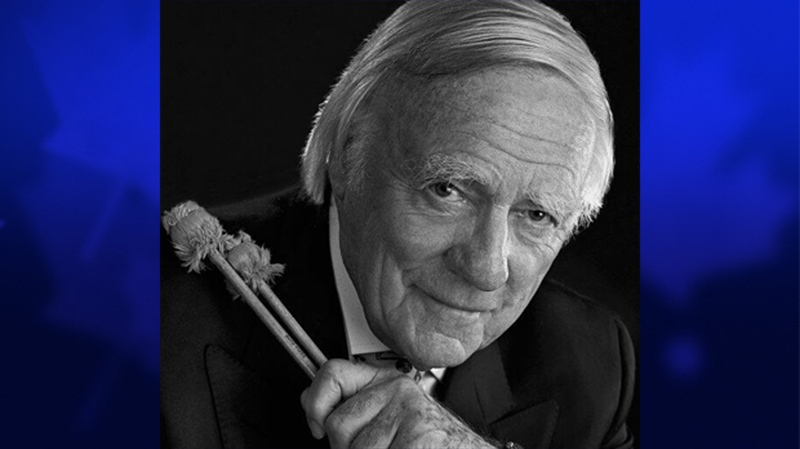

TORONTO -- Peter Appleyard was remembered by friends and colleagues as a seemingly effortless master of the vibraphone, a buoyant bon vivant and a Canadian jazz legend.

Appleyard died Wednesday night at home of natural causes at age 84, confirmed his friend and manager John Cripton of Great World Artists.

Over a long decorated onstage career that also included forays into TV and radio broadcasting, Appleyard shared the stage with such luminaries as Frank Sinatra, Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson, Mel Torme and Ella Fitzgerald.

The last of his 22 albums, "Sophisticated Ladies," came out in June 2012 and featured collaborations with a number of younger Canadian jazz chanteuses, including Jill Barber, Emilie-Claire Barlow and Elizabeth Shepherd, who remembered Appleyard as a master player, a charismatic storyteller and a unique talent.

"He is one of our legends," she said Thursday in a phone interview from Montreal.

"He is Canadian jazz, he and Oscar (Peterson) and others. I would put him up there with Oscar. I think he put us on the map. He's our history."

Born in Lincolnshire on the east coast of England, Appleyard became a drummer during the Second World War before immigrating to Toronto in 1951. He started his own band in 1956 and immediately began lining up commercial work with frequent television and radio appearances, including hosting gigs on CBC-Radio's "Patti and Peter" (alongside Patti Lewis) and the CBC-TV program "Mallets and Brass," with Guido Basso.

But his career took a pivotal turn in 1972 when a casual conversation with famed clarinetist Benny Goodman -- otherwise known as the "King of Swing" -- turned into a head-turning position in Goodman's sextet as well as globe-trotting tours for Appleyard.

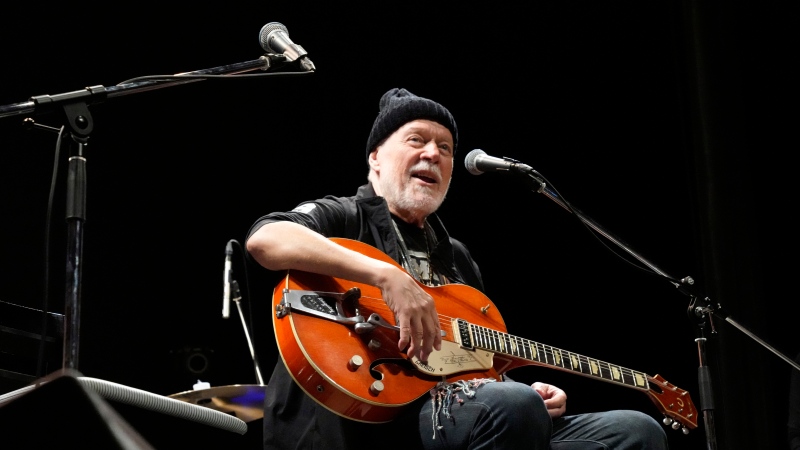

His last performance was this past May, when he and a group of his decorated friends gathered for a night of jazz in Appleyard's barn, including Basso on trumpet, Jane Bunnett on sax, Terry Clarke on drums, Joe Sealy on piano and Dave Young on the bass.

Young met Appleyard in the early 1960s when they played together in Winnipeg. He called Appleyard a "wonderful human being" and said the secret to his vibraphone playing -- in addition to his ability to imbue his playing with an undeniable swing -- was his magnetic stage presence and the feeling he poured into his work.

"Emotionally, he got into the music," Young said in a telephone interview. "Whenever he improvised, you always felt there was a lot of emotion behind what he was playing. ... The audience always picked up on that emotional signal."

Those who worked with Appleyard recently also marvelled at his indefatigable drive.

"He seemingly had endless energy for getting the right take," said Barber, who sang Cole Porter's "Love for Sale" on Appleyard's final album. "Even as a man in his 80s, he was very fluid with the vibraphone. ... It didn't look like he was making any effort at all. It just seemed to be a natural extension of the way his body moves.

"Music seemed to flow right through him."

Shepherd recalled bringing her young daughter -- at the time, not yet a year old -- to their recording session. Appleyard, she said, spent 20 minutes playing and getting to know his tiny studio-mate.

Later, she remembered joining Appleyard to do interviews in support of the album -- and, instead of talking about the music, he kept trying to steer the conversation back to his collection of classic cars. (Cars came up often with Appleyard -- Sealy recalled that in order to stage the concert in Appleyard's barn, his three Rolls-Royces first had to be wheeled to safety.)

In the opinion of his friends and fellow players, it was not just Appleyard's tremendous skill on the vibraphone that won over audiences but also his natural enthusiasm and charming personality.

"Besides being a wonderful musician, he was also a crowd-pleaser," remembered Sealy, who first met Appleyard in 1976 and subsequently shared the stage with him many times.

"People loved him. He was very inclusive with his audience. Basically, he would give you a little background on the tune, how he learned it ... he was carrying jazz history with him.

"He didn't play at people. He played for them."

In 1992, Appleyard was made an officer of the Order of Canada, which Sealy said was a particular point of pride for the musician and one he mentioned often. He also received the Queen's Diamond Jubilee award last year.

Appleyard lived on a farm in Eden Mills, Ont., for the last decades of his life. Friends say he loved nature and was a skilled horseman.

Young visited Appleyard about a week after his final concert in late May, and realized that his friend wasn't in good health. But he still felt well enough to sit and make music, so they joined together for a roughly one-hour jam.

"I could tell he was still excited to play," Young said. "It put him into another world, I would say."