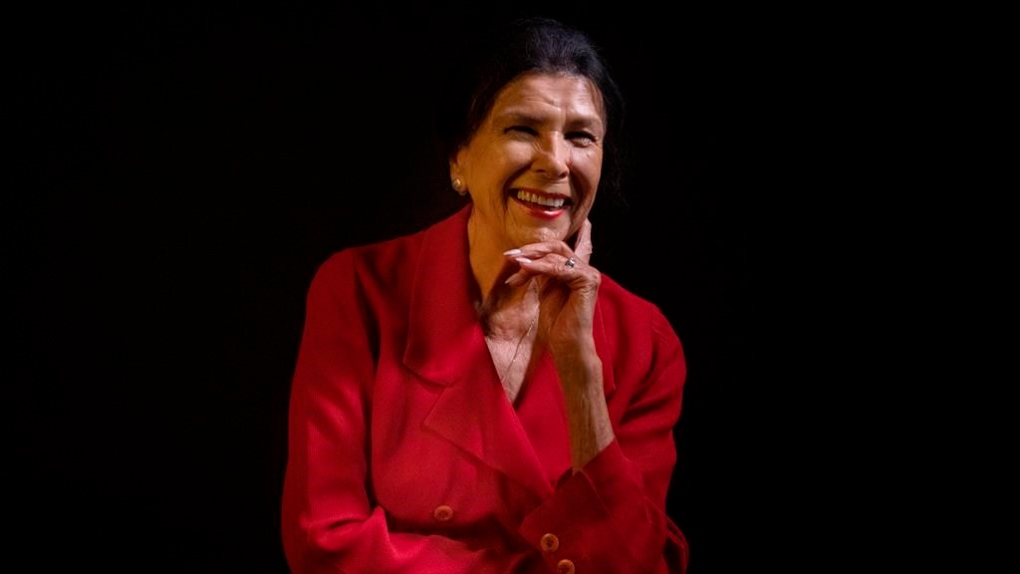

TORONTO -- Alanis Obomsawin has spent much of her career documenting injustices facing Indigenous peoples in Canada, and the wrongs she outlines often overwhelm, infuriate and bewilder.

But for the dogged 87-year-old Abenaki director, the work continues to inspire.

"We're in a much better place. You have to recognize there's been so many people working for this across this country (and) it's different," Obomsawin says of public awareness of Indigenous issues as her 53rd film was set to launch at the Toronto International Film Festival.

"This is why I do what I do (and this film) is very encouraging. I think people will come out seeing that justice is possible."

Obomsawin's latest project, "Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger," examines the decade-long legal battle to secure equal care for Indigenous children with special needs.

It starts with a look at the Manitoba boy who inspired a 2007 law known as Jordan's Principle, which was supposed to guarantee equal access to health care and services but was continually ignored in ensuing years.

Even when the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal issued a ruling that resolved a debate over jurisdiction, many Indigenous children continued to be denied care until several more mandatory orders were issued, the film recounts.

Much of the film's emotional power comes from the painful story of little Jordan River Anderson of Norway House Cree Nation, who was born in 1999 with a rare muscle disorder known as Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome.

In 2002, Jordan was cleared to leave the Winnipeg hospital in which he had spent his entire life for home-based care in the city, but the federal and provincial governments could not agree on who should pay for medically necessary modifications to his foster home. He died in hospital at age five in 2005.

In the documentary, family members and caregivers tell Obomsawin the ordeal was especially hard on Jordan's mother, who had three other small children more than 800 kilometres away on the reserve, but couldn't bear to leave Jordan alone in hospital. She died just months after Jordan did.

At last count, Jordan's Principle has helped fund care for 216,000 children, says the Montreal-based Obomsawin, noting it's gratifying to offer a happy ending to the saga.

Last week, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal awarded more than $2 billion in damages to First Nations children and their families who were separated by a chronically underfunded welfare system. The decision includes compensation for children separated from their families because proper medical support wasn't made available to them.

"Fighting is very important," says Obomsawin, whose landmark documentaries include 1984's "Incident at Restigouche," and 1993's "Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance."

"Often people just let it go and that's the last thing they should do. Because if you keep on and you believe in something and it's just, you're going to win. I don't think anybody could tell me otherwise."

The hour-long movie is the seventh in a recent series by Obomsawin for the National Film Board devoted to the rights of Indigenous children and peoples. It began with 2012's "The People of the Kattawapiskak River," and was followed by "Hi-Ho Mistahey!" in 2013, "Tricky or Treaty?" in 2014, "We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice" in 2016, and "Our People Will Be Healed" and "Walking with Medicine," both in 2017. Most are available to stream for free at NFB.ca, with "Walking with Medicine" available on CBC Gem.

Obomsawin says she didn't conceive of the individual films as connected to each other, simply tackling each topic as they emerged.

But she agrees that taken together they trace a damning history of racism that is still not fully grasped by many Canadians.

"People don't know anything, for instance, about treaties," she says. "When they look at 'Trick or Treaty?' they're just flabbergasted. Up to about 10 years ago, even, if you said the word 'treaty' white people said, 'Oh, don't talk about that! That's finished. It doesn't exist.' But it's not true."

Obomsawin traces her devotion to Indigenous stories, especially those involving children, to her own childhood experiences with the discriminatory education system of her youth.

"The history of this country was taught officially in the classroom and all of it was very racist towards our people -- a lot of lies and stealing of land and national resources. And teaching officially in the classroom that we were savages, (that) we scalped the poor white man who came here," she says.

"I said to myself: The children have to hear another story. (Schools) are raising children to hate, teaching hate towards the people, what is that? So I have done what I could, in my own way."

Obomsawin says she's lucky to be healthy and possess the stamina to travel the country and meet all of her subjects, many of whom pour their hearts out to her. The work can be draining, she allows, but nourishing, as well.

"It's more important to think of the people themselves. Most of the time they don't know how beautiful they are," she says.

"I'm a person who listens for hours with people and I don't get bored. I just find it sacred. It's the voice of the people and what they're going through and you see the magic of it at the same time."

"Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger" premieres Tuesday, with additional screenings Thursday and Saturday.

It also screens at the FIN Atlantic International Film Festival in Halifax, the Calgary International Film Festival, and Vancouver International Film Festival, with more festivals to come.