Day 1

It’s been nearly 48 hours into my journey in Jordan, and I find myself at a loss for words. Already, I’ve experienced so much in so little time, and I look forward to the abundance of knowledge and experience I’ll gain over the next three weeks here.

So where to begin?

I arrived in Amman after a 27-hour journey from Toronto. I was immediately captured by Amman’s beauty, and I arrived in the dark!

It was hard not to be entranced by the stars that spilled out in every direction over the empty black desert/sea (not quite sure which one I was looking at, it was 2 am after all). It was quite symbolic arriving at night, being welcomed by the unknown, but excited for the opportunity ahead.

So why am I here? CTV News has partnered with a media development organization called Journalists for Human Rights – training journalists on all kinds of platforms, from different backgrounds, and at various levels and skill sets.

I’m here to run a three-day workshop with Syrian and Jordanian journalists, to exchange information and knowledge on infographics and incorporating multimedia into everyday reporting.

After a tour of Amman on day one with JHR trainer Mohammed Shamma, the real work began.

Day 2

My second day started off with a visit to 7iber – pronounced ‘hibber’ – an online publication in Jabal Al Wiebdeh, a bustling part of Amman, atop a steep hill. We drove there, of course, as Amman’s topography isn’t exactly conducive to walking – it’s a culture of cars in a city of hills.

7iber started off as a platform for bloggers to publish their blogs. They contracted with professional journalists soon after to publish more in-depth and informative stories, and then became what they are today.

Their office is definitely different than CTV back home. The close-knit team of dynamic young workers share a converted multi-bedroom-turned-office apartment space. It will be interesting to work in the open and airy atmosphere in the coming weeks.

A quick walk throughout this part of the city, and any part for that matter, and it’s clear there’s an election looming just around the corner. On September 20th, voters will head to the polls to elect their preferred party.

Colourful campaign posters line all the street lamps and available wall space, looking to earn the Jordanian vote.

This year’s election is special – it has the most women in Jordan’s history up for election. There’s at least one woman in each party. Mohammed Shamma explained there’s a new law to fill a quota to make sure that women are a part of Parliament.

Next stop was the Art & Tea Café – appropriately named with walls filled with posters, an old television converted into a fish tank, and of course, tea!

Mohammed Shamma and I sat down with Ezz Natour, one of the journalists participating in the workshop and someone I’ll be working closely with on a project throughout my three-week stay.

Sitting down sipping Turkish coffee with the call to prayer -- or “Athan,” as I was taught -- echoing in the background, the three of us discussed an idea for a human rights story that we can cover while I’m in Jordan.

What Ezz Natour came up with was eye opening. He started off by telling us the story of a famous boxing club in a refugee camp that was suddenly shut down. This place was the perfect space for youth in the Baqa’a refugee camp to have something to do; it has even produced a few Olympians and World Champions.

Baqa’a refugee camp was created in 1968 and sits about 20 kilometers north of Amman. It’s home to roughly 100,000 Palestinian refugees, and started out as an emergency refugee camp for Palestinians fleeing the West Bank and Gaza Strip during the Arab Israeli War in 1967.

Nowadays, it’s more like a bustling city, but it isn’t free from its problems. Ezz Natour explained that these sorts of places have become hot spots for recruiting extremists to go off to Syria.

Ezz Natour is hoping to find a few characters to help illustrate the problems faced in this particular camp, and why people turn to extremism. What’s changed in the camp that has led to extremism? He used the permanent closure of the boxing camp – something for youth to do and enjoy – as a potential example of services no longer available.

The three of us sat at the café, going back and forth with ideas, on how exactly to cover this kind of story. While it seems like a tall task, it’s an important one to cover, and a look inside a camp that isn’t necessarily top of mind for many Jordanians, or people in general.

Ezz Natour is a journalist hoping to expand his knowledge and develop his work on more platforms than just online. That’s where I come in. I suggested ways to incorporate multimedia, infographics, and posting longer, raw interviews online in a link within the story.

Right away, it was a perfect example of the exchange of information that’s supposed to take place here, and to be frank, I’m more excited than ever to help.

Tomorrow is another day of touring media facilities here in Jordan, and with the progress already made on day two, I can’t wait to see what’s in store.

More tomorrow!

Day 3

As I sit outside on the rooftop terrace restaurant of my hotel, I’m in awe of my surroundings.

The sun is just setting over hilly Amman, the lights are dim, and there’s something paradoxically peaceful about sitting in a place, unfamiliar in its entirety, with a language echoing in the background that I don’t understand, yet somehow feeling at ease.

That’s Jordan in a nutshell.

The people, the food, the culture, and the beauty – it’s all so inspiring.

As is the work I get to partake in here.

Earlier in the day, I met with Nadine Nimri, a well-respected and award-winning journalist that I’ll be training and working on a project with. Nadine is a reporter for Al-Ghad Newspaper, a well-read paper with fifty thousand subscribers.

We sat down at her desk to discuss an idea for an upcoming story. We were quickly interrupted by the ringing of her cell phone from Angelina Jolie’s people.

Yes, that Angelina Jolie.

She’s in Jordan, and toured Azraq Refugee Camp yesterday afternoon – the same camp I’ll be visiting in about a week.

Nadine told us about the press conference she attended at Azraq and how you would never be able to tell Angelina Jolie is a Hollywood star. It was clear that she was there for the kids, and the cause.

There was a table for those attending the press conference with water, juice, coffee, and biscuits. When the journalists were finished with them, the biscuits and plastic bottles were left, and the kids were ecstatic.

Not about the potential treat, but for the bottles – Nadine explained how they use them to make a variety of things, including toys.

It reminded me a lot of my time in Kledzo, Ghana, where I volunteered in my last year of university. In our tiny and remote village, the kids would collect the garbage from our hut, and turn our seemingly useless trash into something they could use. That empty tub of face wipes? It became a dustbin. It was the same scenario here, at Azraq.

After the slight distraction from the Hollywood glitz and glam, Nadine, Mohammed and I discussed potential story ideas.

Nadine was fresh with a few pitches. One of them was about a woman from Bulgaria, who got in contact with Nadine out of the blue, with an important story to tell.

This woman married a Jordanian man in a civil marriage, and the two decided to move to Switzerland. Her husband then took their three-year-old child on a supposed vacation back to Jordan, but never returned.

So this woman, a foreign mother, desperately tried to get her child back through any outlet possible, including the Jordanian courts, but to no avail.

So how does this happen?

In Jordan, foreign mothers aren’t exactly treated equally. If a woman from, say, an Eastern European country marries a Jordanian man, and they divorce, where do the rights lie when it comes to custody? It’s not usually in the mother’s favour.

But the story goes both ways. Some mothers remove their children from their Jordanian fathers, never to be seen again.

So what about the child’s rights to know both of their parents?

It’s a story people don’t discuss – it’s almost taboo. But it’s important, and that’s where Nadine and I come in.

We barely scratched the surface of this all-too-frequent tale, but it will be an interesting subject to cover, and a scenario that is drastically different than the norm back home.

Next up was a tour of the Al-Ghad facilities. The building is very modern, and looks much like the newspaper buildings back home.

It houses about 350 employees – with everyone from journalists to the human relations department, to the printing press – right in the same building.

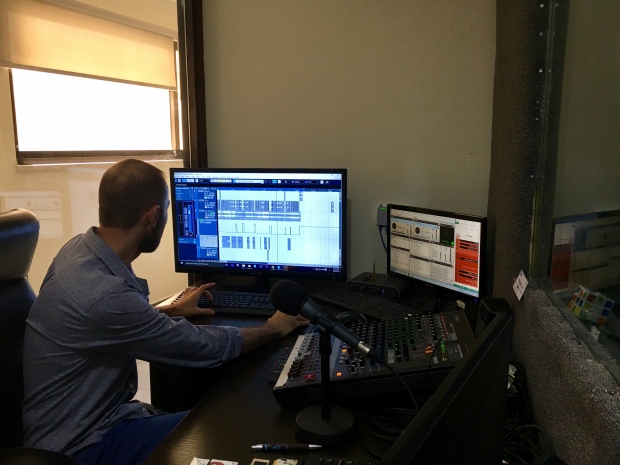

We met with one of the video journalists, who, along with another colleague, recently started the video component of Al-Ghad online.

They’re able to put together one or two full reports on the website per month. It seems like a small start, but they’ve had to teach themselves entirely from scratch.

He showed us examples of interviews – one about synthetic marijuana on the streets of Jordan called joker that is wreaking havoc – as it’s made almost entirely from chemicals. It reminded me a lot of the recent Fentanyl crisis in Canada.

I was asked what I thought about the stories and immediately wanted to share a few tips from my television background.

Through the interpretation of Mohammed and Nadine, I explained the importance of pacing of shots, keeping clips to a maximum 15 seconds (at least we try to), and how to keep the audience engaged.

There is an obvious divide between departments at Al-Ghad and not a lot of multimedia going up on the web. I suggested a way to incorporate a variety of platforms for one single story.

Nadine and her colleague looked at me with eyes wide open as I explained putting a short story to grab a viewer’s attention above a longer, written feature up on the website. Based on my CTV experience, it’s also effective to embed or link to a longer version of the interview within the article itself.

At least back home, it’s hard for people to stay engaged and pay attention for longer than a few minutes – and even then, that can be a stretch.

I was always apprehensive and even a little bit worried about making a difference while I’m here. Anyone would be, it’s an incredible opportunity and I want to do well.

Luckily, with these visits and exchanges of information, knowledge, and expertise, I do feel like I’m making a difference, however small, in my short time here so far.

The seeds have been planted, and that’s all I can ask for.

I can’t wait to see where it all leads.

Day 4

It’s the day before Eid in Jordan, and needless to say, many people have taken this extra day off before their real holiday begins.

Much like a long weekend being extended with a Friday off back home, Amman has kind of shut down for the day, and so has the work …for now.

I decided to take a trip to the Abdali Mall. It’s in an area of Amman called Boulevard, and it’s being hailed “the new downtown.”

The mall of all malls #abdalimall #amman pic.twitter.com/d8pd1VCkmo

— Kaleigh Ambrose (@kaleigh_marie_) September 11, 2016

Some Jordanians aren’t too pleased with the new description, as Amman’s historical and original downtown is much, much different. It’s filled with markets, the smell of fresh kunafa being made (a local treat of baked cheese, fried breadcrumbs and honey), gold vendors, and a whole lot of life.

This particular topic has come up in conversation a few times with residents of Amman. They’re not insulted by the new designation, per se, but annoyed at the huge modern buildings making their way smack dab in the centre of the city, and the assumption that just because it’s new, it’s the official downtown.

It’s the eternal struggle of new replacing old, and trying to find a middle ground.

The first order of business on my way downtown: hailing a cab.

I walked outside of my hotel in the blistering heat – you’d think I’d be used to it by now – to catch a cab on the main street. I must have had a sign on my forehead that I needed to get somewhere, because a cab sped by me, quickly reversed, and asked where I needed to go. Easy enough!

I’d been warned about taxis and the drivers running the meter to charge a fare that isn’t justified. So, I asked the cab driver how many JDs (Jordanian Dinar) it would be to the mall. He didn’t speak a lot of English and pointed to the meter.

At that point, I was just eager to get out of the sun, so I accepted whatever fare was in my future.

A couple of checkpoints later (there is a security checkpoint for all cars entering the “downtown” mall area), I paid my likely double fare and was on my way to exploring.

Abdali Mall is unlike anything I’ve ever seen in my entire life. Grandiose and extravagant are two words that come to mind, but even those descriptors don’t do it justice.

It’s similar to the Toronto Eaton Centre, except it has a couple more floors, it’s double the size, has a metal detector at every entrance, has an outdoor market and an open roof. On second thought, it’s nothing like anything we have back home!

So what are some other similarities and differences between Amman and Toronto?

I learned yesterday that crosswalks aren’t really a thing, here in Amman. It’s all a big game of chicken when it comes to crossing the street. Most of the cars were nice enough to stop. I’ve learned that people will cross whenever they feel like it, so if you’re on the other side of the equation and driving, you’d better stop!

As it turns out, crosswalks aren't really a thing in Amman pic.twitter.com/YjtTUPtU37

— Kaleigh Ambrose (@kaleigh_marie_) September 10, 2016

There isn’t really a recycling program in place here. There’s been a small movement, but the infrastructure to implement it simply isn’t there. I’ve found myself holding onto the dozen water bottles that I finish a day, waiting for a recycling bin, but finally giving up.

Speaking with different people, it was funny to note how similar we are when learning a new language. I was asked what words I already know in Arabic, and I shyly admitted that I know “thank you,” or shukran, and everything else is a bad word.

Everyone laughed because they admitted that they too, learn those when they’re first introduced to a new language.

Mohammed has also noted that I pronounce my city’s name differently than what he’s heard before. I say “Torono,” as any good local does, instead of “Toronto” with a second ‘t.’

I explained to him that it’s a funny way to decipher if someone actually lives in the city or not.

I also noticed that seatbelts aren’t the norm in taxis here. Either way, I made my way from the mall back to my hotel, negotiated a fare with a really nice Jordanian cab driver, and successfully survived my first trip in Amman by myself.

Tomorrow is an official holiday, so I’ll likely spend the day on the rooftop preparing for my workshops, which begin on Wednesday. I’m expecting 15 Jordanian and Syrian journalists from all different backgrounds – print, online, television, radio – and all with different stories to tell.

I’m excited to see how the workshops go.

Back to planning for me. I’ll have more in the coming days.

Day 5

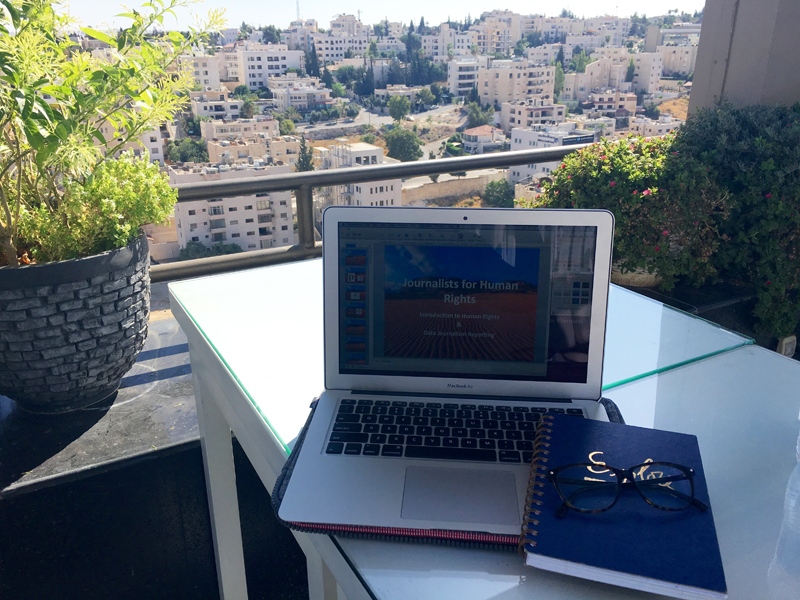

I’ve settled back into my favourite new workspace – the rooftop terrace. In typical polite and eager-to-please Jordanian fashion, they opened it up just for me, even though it didn’t officially open until 6pm.

Today’s a day of preparation. In two days, I’ll be conducting my first of three workshops on advanced human rights reporting and the art of infographics.

Sounds complicated, but I’m trying to make it as easy to understand as possible, which is proving to be no easy task.

Before I left for Jordan, I met with our web team to learn just what an infographic is, and how to put them together.

It’s not something I necessarily do day-in and day-out at CTV, so it was an initial challenge before I even started the work on the ground.

I quickly learned that it just takes a bit of perseverance, and at times, the web team holding my hand and walking me through it.

Now that I’m on my own in Amman, I’ve created a Power Point to help keep the workshop interesting and interactive. I haven’t had to do one of these since high school, so it was another task of picking it back up again. Needless to say, it really was like riding a bike again, no sweat!

When it came to what the online team had taught me, that was another story. It’s been an interesting process having to teach things that I’m just learning myself. I’m proud to say, though, that if I put my mind to it, I can probably do just about anything.

I think solo travel and new experiences really teach you these things about yourself, so it was nice to finally feel like I was getting things accomplished.

Up on the rooftop, I played around with Google Spreadsheets, taught myself how to create heat maps, charts and graphs of all kinds, and a few other infographic tools that I’ll be teaching everyone at the workshop on Wednesday. Who knew how much Google had to offer!

Day 6

The setup has officially begun in the meeting room at Landmark Hotel. I met with Mohammed early this evening to put everything together.

The table is set, with place cards to mark, where people will sit, and the learning will start. It feels like the morning before Christmas, so I thought a little carol-themed poem would be appropriate!

With the only snag being that I need an extension cable for my MacBook to plug into the projector, I’d call the set-up day a success!

I’ll be teaching in English, but each participant will have a headset and microphone in front of them. JHR has hired a group of professional translators – sound booth and all – to translate my entire workshop over the three-day period.

I’m kind of nervous and anxious to see how that process will go. I’m sure it’ll be challenging to teach a subject that’s new to me in a language that my participants aren’t necessarily fluent in.

But we’ll see how that all goes, no use worrying about it tonight.

Tomorrow will be here soon enough, and we’ll adjust if necessary – that’s the name of the game any day that I’m producing with CTV National News, so why should it be any different in this exciting adventure.

Until tomorrow, wish me luck!

Day 7

Let me first start by saying: I have a new appreciation for the work that teachers do!

When I initially set out to create a lesson plan for three days of workshops – not to mention on topics that were new to me – I had no idea how challenging it can be to run a “classroom” and teach.

As I’ve mentioned before, I think this was probably my first public speaking engagement since high school.

All of this is not to say that the workshop didn’t go well, because it most definitely did.

It wasn’t without its initial challenges, though. I knew that teaching through an interpreter would be a new experience, and although mind-boggling at times to wrap my head around it, it worked out really well in the end.

Each participant was given a headset and a microphone, and I stood at the front of the conference room, armed with the same equipment. I’d ask a question or speak, and they would respond, all while alternating between headphones and microphones.

I found that my trusted microphone worked best in my right hand, while dealing with the headset eventually just meant leaving it around my neck.

I’m not sure if I’ll ever fully get used to the teaching tools – it kind of puts an even bigger spotlight on me – but they are necessary challenges in an even more necessary and important task.

We began with an icebreaker activity. I wanted each participant to share their most challenging story and then a story they’re most proud of and why.

It was fascinating to learn that a lot of the stories that we’re proud of are also the ones that challenge us the most, and that’s what makes them so rewarding in the end.

The exchange back and forth of ideas, lessons learned, and ways to overcome difficulties when reporting really showed that deep down, no matter what issues we may face individually as journalists, there’s nothing quite like putting your all into a story and seeing the fruits of your labour.

I was prepared to hear amazing stories of triumph and adversity, but what these Jordanian and Syrian journalists shared were beyond comprehension to me.

There was a Syrian journalist in attendance, originally hailing from Aleppo. She painted the picture of what it was like to work in Syria, saying once it’s known that you’re a journalist, it’s as though you’re automatically an enemy of the State, or an opponent to the Regime.

She couldn’t even think about bringing a camera to film a report, and shot most of her video using her cell phone. Then when it came time to publish her work, there was no support to get anything out there, and she often has to use a pseudonym.

Then there was the founder of the group for Syrian female journalists, who spoke about the challenges of being female in a male-dominated field, or male-dominated world, for that matter.

We went over examples of human rights reporting that have been covered at CTV and what kinds of challenges journalists back home face when it comes to reporting on important issues – issues that aren’t always easy to cover.

Many participants spoke about the benefit of this workshop including both Syrian and Jordanian journalists, because a lot of them face the same difficulties and risks when it comes to their reporting. Many were relieved that they aren’t alone in their daily struggles.

Struggles and challenges like a lack of access to information. These journalists work under intense scrutiny and censorship to get their stories out there. They even struggle with bringing stories to light that matter to a general public, a general public that isn’t always receptive to what these journalists want to tell.

I quickly realized how much we might take our freedom of access to information for granted. It’s a right that we have as a people, but it isn’t the same story across the world.

Another journalist shared her story about gathering information and reporting on a story about Syria from Jordan. Communication back and forth took over a month – with Internet problems galore – to produce a 3000 word story.

I think what we all shared from this experience is that journalism is a profession of challenges, big and small, far and wide, life and death.

So in the end, why do people choose to become journalists? What is it about the dangerous and complicated work that makes it so attractive?

I put the question to the group.

One participant felt it was her duty to be the voice for a people where media didn’t yet exist.

Another wanted to speak out for marginalized citizens who don’t have a say.

One veteran reporter joked that he’s stubborn and wanted to do what he was told he couldn’t or wasn’t allowed to – and that was to ask questions and know everything about the world around him.

For most, it’s not about calling their day-to-day ‘work’, because it’s their passion.

It was a very eye-opening workshop to be a part of. These ambitious journalists – some brand new to the field and some seasoned veterans – all wanted to share in the experience of learning and bettering their skills.

At the end of the day, no matter my interpretation of how well the workshop went, we’re all better journalists for having shared in the exchange of knowledge.

Tomorrow will be another challenging day, digging into the technical details of creating infographics – an art form that I’m still trying to tackle myself.

But if it’s anything like today, we’re on the right track to something amazing.

Day 8

As predicted, today’s workshop was a whirlwind!

The focus was on data visualization – what it is, how we do it, and why it’s important.

We discussed the importance of data journalism in this day and age. It’s not always an easy process to work with large amounts of data or information, and turn it into a story, but it’s an important skill to have in your back pocket as a journalist.

So what exactly is data journalism?

It’s the process of gathering and filtering large amounts of information and turning it into a story, usually a visual (ie. in a chart or graphic) story, or including it in addition to a written or broadcast report.

It’s a creative and interesting way to enhance a story, or let the data speak for itself and lead you down a path towards an entirely new topic that you may not have thought of.

So how do we actually convey these stories visually?

That was today’s lesson.

I walked the participants through the steps: first you collect data (through surveys, research, etc.), then you clean or filter it (getting rid of any clouding information or doubled up information), and finally visualize it so that it makes sense to your audience.

It was interesting to learn that a lot of the data collection tools that we might use in Canada aren’t necessarily available to journalists in Jordan.

For example, many freedom or access to information requests go unanswered, official websites or departments give the runaround, or people simply don’t want to talk.

Together, the group and I discussed ways to get around these challenges.

Based on my lessons from our very helpful online team, I explained how to create charts/graphs through Google Drive, maps based on location and relevant information (ex: gun licenses per province), online survey creation tools to gather information, and finally, Google Heat Maps, which show the intensity of whatever your data is, framed neatly on a map.

The struggle was apparent today when it came to the language barrier. It’s never an easy task learning something complicated, let alone by a teacher speaking in another language.

The interpreters went back and forth between Arabic and English to relay my message and also to ask any questions from the participants.

Luckily, today’s workshop was about just that, working! A lot of the day was spent actually using these tools and having something to show from the lesson plan.

I sat down with most participants individually – some understood more quickly than others – and we both tried our best to understand one another and the material at hand.

Once everyone got the chance to try out the various tools for themselves, I showed them examples of work that CTV has done over the last few months.

We looked at a long report on World Refugee Day, an in-depth breakdown of the Fort McMurray Wildfires, and the recent terror attacks throughout France.

(Below: with JHR trainer Mohammed Shamma and workshop participant Abdallah Momani)

You could tell it was eye opening to the participants of the workshop just what kinds of multimedia can be incorporated into any old story, to make it interesting and keep your audience coming back for more.

The questions from the students were passionate and I tried to make my answers as clear as possible, and overall, the day ended on a high note.

I’m looking forward to tomorrow’s final session, where we’ll discuss how to cover an election. The election on September 20th in Jordan is quickly approaching, so it’s a very pertinent issue to cover.

Everyone will create their own visualizations and do a presentation, in order to earn their “passing” certificate from the program.

It’s going to be a great final day to see how far everyone has come, including me!

Until tomorrow,

Day 9

Elections, elections, elections! What can be said about elections?

A whole workshop’s worth of knowledge, apparently!

Today's workshop focused on election coverage, journalistic tips, and data visualization and infographic examples, to bring an election to life for viewers.

Before we got into CTV examples, the journalists and I discussed challenges we face when it comes to covering an election effectively.

I gave a few examples of remaining impartial, bribery, etc. but their examples were something else.

The situation in Jordan is obviously very different than the situation in Canada. While we all share the same goals of covering an election in a fair and just way, it isn’t always possible.

The participants explained that it can be hard to know what issues or topics to cover because there’s a lack of actual data to collect. Many of the statistics are outdated.

A number of people in Jordan never really get the chance to know the candidates, and therefore don’t bother voting. The information isn’t out there and there’s a lack of credibility, so it can be daunting to bother hitting the polls.

It was interesting to see that halfway around the world, everyone struggles with the question: will my vote matter?

After a heated discussion, it was time to get to work.

I gave the participants homework last night to poll their friends and family about something political.

Today, their task was to visualize this data that they came up with. First task: a graph. Second task: a map.

Side by side, we worked together to put what we learned yesterday to use.

Some needed more help than others, but it was an honour to be able to assist them, even in such a seemingly small way.

It was difficult, at times, to reach everyone and help each participant with their data visualizations, but luckily, they helped each other. Some even came up with new ideas in addition to what was taught in the lesson.

It really goes to show you how much they learned, when they’re able to help themselves and one another.

There were questions through interpreters, smiles when participants finally understood or grasped the concepts, and a true display of what happens when people work together and exchange knowledge.

Each participant gave a short presentation on the results of their work, and were handed a certificate for participating in the workshop.

I’ll never forget when one of the participants who seemed to have the most trouble, excitedly volunteered to present first. She was beaming from ear to ear, and proudly showed off all that she was able to accomplish.

It’s those kinds of moments that really remind me why I’m here.

It was great to hear that some were dreading having to do a presentation and discuss their work, because they weren’t sure that they could do it. It turns out, though, that practice makes perfect with anything and everything.

Some of them thanked me for their help and explained how they’ll use these tools in the future. It’s exciting to know that these lessons won’t go to waste and that I actually made an impact already.

Funnily enough, when we were finished and it came time to take a group photo, the same scenario played out in Jordan, as it would have in Canada.

Getting a group of 15 or so people together to take a photo can be difficult, to say the least. Everyone wanted to take selfies and pose in their own way, but eventually, we ended up with a great group photo.

No matter what separates us geographically and circumstantially, some things will never change!

As I reflect on my three-day workshop, I’m honoured to have participated in this experience. Teaching journalists in Jordan, though challenging in another language, was something that I’ll remember forever because as much as I taught them, what I learned is also invaluable.

It’s never an easy thing to keep pushing yourself to learn new things, but you could really tell that each participant wanted to be there. It wasn’t forced knowledge or forced information spewing from the front of a classroom. It was understanding and results.

Day 10

In less than 24 hours, I’ll be on my way east of Amman to the Azraq Refugee Camp.

Surreal is the only way I can describe how I’m feeling, because this opportunity and experience is unlike anything I’ll probably ever experience again.

Jordan has brought in nearly a million and a half Syrians since the conflict began, and the number continues to rise.

The country itself, is home to roughly six million people, so as you can imagine, it’s struggling to find a place to house everyone.

So they decided to build the Azraq Refugee Camp. It’s the newest refugee camp, constructed in the remote Jordanian desert and opened in April 2014.

It’s a city built from scratch, in the middle of a desert that stretches as far and wide as the eye can see.

The planned community is unlike any other refugee camp, because this one was built very strategically and carefully. The others are usually built hastily, in response to a disaster.

The rows upon rows of white steel shelters are sectioned off into small villages, where in total, about 36,000 Syrians presently live, according to a recent United Nations High Commissioner for Refugee (UNHCR) report.

They come from places like Damascus and Homs, where turning back isn’t an option.

I hope to be able to speak with a few families living at the camp and see what life is like inside Azraq.

What is the access to education like?

How do families spend their days?

What’s a day in the life of a Syrian refugee family, living in the middle of the barren desert?

Tomorrow, I hope to find out.

Day 11

For some reason, I couldn’t really sleep last night. I must have had a big day ahead of me, or something!

We set off for Azraq bright and early, driving through eastern Amman, a visibly poorer part of the city. Teenagers played soccer on the asphalt in a giant parking lot, unbothered by the sweltering heat, even at eight in the morning.

The cramped houses and apartment buildings started getting fewer and farther between, and I had just started to doze off, when we were waved over by police on the side of the highway.

Great, another checkpoint, I thought.

It turns out; our yellow and green cab drew attention because we were passing in an area usually frequented by yellow and blue cabs.

A quick conversation with the officer and we were on our way.

It wasn’t an unsettling experience, and it also wasn’t the only trouble we’d have with our cab. More on that later!

The bumpy highway continued for an hour and a half outside of Amman, and as we inched closer and closer to the camp, nervousness washed over me.

Perhaps it was the lack of blue skies and instead, an eerily white haze of heat over the desert.

Regardless, it was an overwhelming feeling being so close to such an adventure.

We went to about three different entrances to the camp, only to be turned away and sent to another one.

Finally, we reached an entrance and it looked like we were making progress. That is, until we were officially told we wouldn’t be allowed inside today…at all.

Apparently we weren’t allowed to enter the camp because we were driving in a taxi, and not a private car. We decided to take a chance and head to Azraq City to get a rental car, but were told over the phone that that wouldn’t be allowed either.

By the time all of this was sorted out, it was nearing noon, and our written permission to the camp was only good until three.

Now, even though we had this written permission from the Media Commission in Amman, and were never warned about any specific car being an issue, we were turned away.

We trudged along the dusty highway back towards Amman to speak with the very commission that gave us our papers in the first place.

The director of foreign media sits in an office on the third floor, near the “new downtown” in Amman. Cigarette lit and smoking from the ashtray on his desk, we were waved in to sit down on the leather chairs just in front of him.

A few important-looking men walked in and out of his office, one dressed in a UNICEF uniform, all speaking Arabic to one another.

Needless to say, I didn’t really have a clue what was going on.

Eventually, they explained that there seems to be a disconnect between the Media Commission and the actual camp, and it’s been a logistical headache for a while now.

He gave the example of last Friday, in the middle of Eid, when several journalists were turned away because the camp was “closed.”

Bureaucracy at its finest.

The commissioner suggested we visit another umbrella commission, which handles all Syrian refugee camps in Jordan.

After several glances at our permission papers, passports, press cards and more, we finally received another form that will register Mohammed’s car to drive us to the camp tomorrow.

I sat in the dimly lit office, with shiny white floors, and the smell of cigarette smoke wafting through the room, waiting for Mohammed to finalize everything.

One officer came up to me and started speaking French. I thought I was being pranked, but Mohammed had mentioned to him that I’m from Canada and am bilingual.

We spoke briefly about my work in Jordan, why I know French, his background with the language, and his happiness to have a conversation in “la langue des oiseaux,” or the language of the birds.

I later had to look that up. In simple terms, it means an angelic and mystical language – he’s clearly a fan of français.

Tomorrow will hopefully be a more successful day of storytelling – preferably that of the refugees living at Azraq, and not my own.

Here’s hoping!

Day 12

Few experiences in life change you the moment they happen to you. My short time at Azraq Refugee Camp is one of those rare cases.

It was both unforgettable in the way it challenged me, just by the very nature of my surroundings, but also enlightening in the stories of triumph and defiance that were shared with me.

It was unlike anything I've ever felt in my twenty-six years on this earth, and I know I'll never forget it.

Getting There

We arrived bright and early, on another blistering hot morning. A quick checkpoint inside the main gate we waited at yesterday, and we were met with smiles this time, instead of frustration. It's amazing what several permission forms will do!

For context, the camp is 90 km from Syria, 255 km from Iraq, and 75 km away from Saudi Arabia.

The camp sent a worker with the Interior Ministry of Jordan to lead us around for the day. We were lucky to have him, as the camp sits on an enormous stretch of land.

Azraq is nearly 15 square kilometres, and has the potential to house over 100,000 refugees, making it the second largest refugee camp in the entire world. The first is Dadaab camp in Kenya.

Azraq was built on the same site where Iraqi and Kuwaiti refugees were housed during the Gulf War in the early 1990s.

It was used as a transit camp then, and it's clear that Azraq isn't meant to be a permanent solution now either.

Our guide brought us up to the highest point of the camp, overlooking the vast landscape of rows upon rows of white steel and tin caravan houses.

Over 36,000 people have escaped something they can no longer go back to, and now call Azraq home, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Coming up over the hill, it was as though we were peering over some sort of prison scene out of a movie on Mars. Dusty roads, surrounded by sand and rocks, and these white steel "tents" lined up in neat little rows, sectioned off in neat little villages.

None of it seemed real.

But it's reality at Azraq.

The Set-up

The camp is divided into villages, each one with a number, a certain amount of rows, and a certain amount of caravans per row. It's an organized system, down to an art form.

The villages are separated based on family types – so single women in one area, families in another, etc.

Families of up to seven people live in one house, anything over that and they're given a second shelter.

Each village has a school, where boys and girls attend separately. The girls in the morning, and the boys in the afternoon – every child has access to education.

Access to energy and electricity is another story. There's a plan in the works, with solar panels lining the road when you enter the camp. The goal is to provide enough power to operate lights, a fan, keep food cold in a fridge, and maybe even watch TV.

It's a work in progress, with solar streetlights and lanterns being distributed by UNHCR in the meantime.

The Market

Electricity isn't the only issue. Unemployment is high at the camp, as well as in Jordan in general.

One way UNHCR has tried to combat this is with two market areas operating inside the camp walls.

In total, there are 200 shops, half of them owned by Syrian refugees in the camp, and the other half by Jordanians in surrounding communities, outside the camp.

You can buy anything – from Nescafe specialty coffee, to hair clips, to bicycles, to phone repair services.

That's where we met Nedal, a 28-year-old man working inside a cell phone repair hut.

He escaped Daraa, Syria with his wife and child five years ago, and has been living at Azraq for a year.

Tinkering with the back of an open cell phone, he explained what he left behind.

"In a word, disaster," he said, through JHR trainer Mohammed Shamma, as my interpreter.

His town was under siege by the Syrian Regime, and destroyed everything in its path.

He escaped to Irbid, Jordan, but was there illegally. Jordanian police were forced to transfer him and his family to Azraq, instead.

Walking along the neatly lined shops, we then entered an accessory store.

The owner, 38-year-old Faisal, escaped Homs in 2014 with his wife and their seven children.

Faisal is one of the originals at Azraq, here since its opening in April 2014.

Back home in Syria, he worked in a shop very similar to the one he now runs in the camp. UNHCR helped him set it up, with supplies and a space, to make life seem as normal as possible.

But the situation isn't as normal, or as easy, as he wishes it could be.

"People don't have money," he said, with frustration in his voice.

Every person at the camp is given 20JOD (roughly $37 CDN) per month from the World Food Programme.

This usually goes towards the expensive grocery bill, leaving little room for extras, like those sold in Faisal's shop.

But at the end of the day, he's happy to have a job and a place to earn a little extra for his family.

"What can I do, I have nothing to do but this shop," he said.

Add to this the story of Jumala, a 31-year-old single mother who left Hamas when her husband was killed in the war.

She lives in the sixth village with her three and a half year old son. She leaves him with their neighbours when she goes to work, because they've all become like family.

A new family, a family she no longer has close to her.

"You leave your home and an explosion happens beside you, I remember, it was so hard," she recounted. "How can I deal with this bomb and take my child and run away from this bad situation."

That bad situation killed both of her parents and two of her siblings.

She was with another sister in a nearby town, and survived the explosion that took her family and her childhood home.

She has relatives in Canada, Lebanon and some who still live in Damascus. She said it's hard to communicate with any of them and know how they're doing, but she thinks about them constantly.

As for her one wish for her scattered family?

"I wish to be with all of them, here."

She's made Azraq her home and doesn't plan to leave any time soon. It's as stable as life can get for her right now.

When things calm down in Syria – if things calm down in Syria – she'll return to her former home.

"What can I do? I will survive," she said.

Familiar Hospitality

Survival is the name of the game at Azraq – everyone is just trying to live their lives.

We walked to the third village, just outside of the market, to meet with some families. None of these meetings had been set up ahead of time; they simply invited us into their homes to share their stories.

On our right, and two houses in, Mohammed welcomed us into his caravan.

He held back the plastic makeshift door covering, cut into strips from a UNHCR tarp.

We removed our shoes in the front hall of his home, and he told us to sit wherever we wanted.

The floor was lined with orange and blue UNHCR burlap mats, and grey mattresses circled an open space in the centre of their home.

Mohammed is 32 and lives with his wife and their two young children. His daughter is four and a half, and his son is only six months old, born in the camp.

He explained proudly that his daughter will start pre-school next Sunday.

Mohammed's story is unique, in that he moved around from place to place before deciding it was time to get out of Syria.

His family lived in a few towns, but Syrian police kept following him around, and they felt it was best to leave.

The final straw came when air strikes began decimating Damascus.

As for life in Azraq?

"I'm satisfied with my situation here," he said. "It's not bad here but I'm not comfortable with the weather and dust and everything."

He's not alone.

For many, summer is the worst at this camp. The dust and heat alone would drive anyone to leave, but there's nowhere to go. Given the chance, though, Mohammed would take it.

"Give me five minutes, I'm ready with my family."

To pass the time, he explained that his family naps, plays with their birds (they have a pigeon coup beside their home), visits the markets, or works.

Mohammed was a restaurant worker back home, and wishes he could find a similar job here, at the camp.

For now, he works at a cleaning centre for a few extra dollars a day for his family.

There's an Incentive Based Volunteering (IBV) program set up for refugees, where they play an active role in how the camp actually functions, and earn some extra income.

Mohammed says it's not much, but it's something.

A brief moment of silence is broken by the laughter of the dozen or so children who have followed us into Mohammed's home.

They keep glancing at me and giggling, playing peek-a-boo between interview questions, and coyly trying to draw my attention.

We finished the interview and headed outside to see Mohammed's birds, and the children followed.

We all high-fived, and I made sure each and every one of the kids felt special, at least for a brief moment.

As we walked away, a girl, maybe only ten or eleven years old, declared "I love you," staring up at me with her big brown eyes.

The heart pangs were immediate, and I turned back several times to continue waving to them.

Another girl ran up to us and asked disappointedly why we didn't ask to visit her home. She called out to her mother, who didn't want to be interviewed, even informally.

Our guide explained that many women don't want to speak about their experiences without their husbands present; it can be a cultural thing.

It wasn't an issue , though, for Omad and her daughter Leila, who saw us walking down the row of shelters and invited us inside.

We were warmly welcomed into their strategically decorated caravan. Sheets hung a third of the way through the room, acting as a divider for privacy. The same UNHCR mats and grey mattresses were spread out, much like Mohammed's house.

This mother and daughter pair stayed home while the husband and son of the family were in a nearby town, waiting for surgery.

The father has an ulcer, and though emergency services are provided in the camp, surgeries are another kind of medical issue best dealt with in one of the nearby hospitals, with UNHCR covering the cost.

The family escaped their dangerous life in Homs nearly six years ago, when the first signs of the Arab Spring had sprung.

They set out for Aleppo, but the situation took a turn there as well, and they decided to move to Jordan, since other members of their family live here.

The tight-knit family has another son living in Istanbul, Turkey, and if given the chance, they'd leave to all be together.

"The situation in the camp isn't good, but [it's] definitely much better than Syria," Omad explained. "It's not easy, there's no opportunity for work here."

Her husband has struggled to find work in the camp. He was able to find a job for a month, but it didn't last – she didn't explain why.

We were interrupted by her two friends yelling through the window about a sale at the "mall," or grocery store.

It was a good enough deal for them to come inside and sit and tell us about it.

A Sale is a Sale

A drive away from the third village, or roughly a 15-minute walk, and you reach the Sameh Mall, aka the grocery store.

Today, all produce was on sale and it was busy, to say the least.

We met a man at the market named Abdullah, who stood beside us in crutches, and immediately wanted to tell his story.

He left Aleppo with his wife and their 10 children. He hurt his back when a bomb went off next to him, and shrapnel ripped through his body.

He still has trouble walking, but is glad to be alive.

That doesn't mean he's content with his current situation, though.

He explained that the money given to each family isn't enough to support an actual life. Yes they receive money each month, and loaves of bread daily, but the food is expensive and a family of ten goes through it quickly.

It can take two hours just to buy groceries, and that's when there isn't a sale.

Throngs of people snaked through the grocery store with their boxes of produce and goods in front of them, waiting in line to buy everything. Always waiting.

When they eventually reach the front, their electronic vouchers come up on the computer. Through an EyePay iris scanning system, the registration database shows how many family members are in each family, in other words, how much money they have to spend on food today.

Dancing Forward

Another necessary part of life: moving forward.

We hopped in the car and made our way to the UNICEF after-school program area.

Azraq is dotted with basketball courts, soccer pitches and other such centres for people to pass the time, but the work being done at the UNICEF centre is unlike anything else.

Much like regular school, the boys and girls are separated, but all have a chance to partake in the variety of activities available to them – from a painting centre, to computer labs, a soccer field, teakwondo lessons, to life skills and development teaching.

We met with Noelle, a refugee herself, who is now a teacher at the activity centre. She quickly put on a cartoon for the children to watch, while she explained the work she and her team are trying to accomplish.

They usually have 30 to 40 participants, and aim to give shy or scared children the opportunity to flourish.

She explained that it can be a struggle when girls are coming from terrifying lives in Syria and become afraid of their surroundings, even at the camp. The change alone is enough to make anyone nervous.

The activity centre provides these children a place to be themselves and learn how to deal with all of life's difficulties – both old and new.

The children get together either outside, or in one of the trailers on site, kind of like a classroom. The one we visited was decorated with colourful artwork and crafts, all sorts of happy things you'd see at any school back home. There's also a Canadian flag on the wall, as the centre is partially funded by Canada's support.

I let the girls get to their Zumba lesson, as I stepped out of the trailer to speak with Malek Al Bitar, a project officer with UNICEF and Mercy Corps.

He explained the activity centre is there to provide psychosocial support for kids who come from terrible, extreme, and stressful situations.

"Adolescents from stressful situations…they become more aggressive, they don't like life, they lose themselves," he explained. "What we are trying to do here is just reconnect them."

It seems to be working. He gave the example of a young girl named Roba, who wanted nothing to do with the centre. Now, she's the captain of the soccer team, and thriving.

"Every day is a success story," Al Bitar said with a smile.

Noelle and one of the girls poked their heads out of the trailer and asked if I wanted to come inside to see their Zumba dance.

Without hesitation, I jumped from my bench and headed inside.

As I sat there, watching them give their all – successfully I might add – I found myself welling up with tears. Though I didn't let them fall, the fact alone that I was invited into such a private, yet joyful and proud moment, speaks volumes.

The dancing ended for the day, but it won't as long as programs like these continue for these children.

We pulled away in our car, ready to leave the camp, and three boys approached us and began racing beside us. They waved excitedly, almost begging for my attention and returned gestures from the car.

At the end of the day, all of these stories, and all of these people, they just want to live their lives and make something of their future.

Innocent children have gotten caught up in the middle of a bloody civil war, but through it all, nothing stops them from being just that – kids.

Although there's always room for improvement, and the daily struggle continues for these families, forward is better than anything that was left behind.

Day 13

It’s Election Day in Jordan and a desire for change is in the air.

Today’s a national holiday, giving everyone the chance to vote in this historic election.

Here’s a little background on how Jordan ended up with an election, again.

King Abdullah II dissolved Jordan’s Parliament at the end of May, requiring an election soon after, and this is where we are now.

So how does the system work?

The Parliament itself consists of two chambers. The first is the upper Senate, which is appointed by the King, and the second is the lower Chamber of Deputies, with its members being elected through votes.

In total, there are 130 seats – 15 reserved for women, and 9 are reserved for Christians – and there are 23 electoral districts.

Adults 18 and older hold the right to vote, but there are many caveats to this. For example, people who are bankrupt, mentally disabled and some convicts cannot vote. If you’re a member of the armed forces, state security services etc., you also can’t vote while you’re employed by any of these official bodies.

Elections in Jordan are often based on patronage, with people voting for who they know – strong family ties play a vital role.

But this year is supposed to be different, with recent changes being made to the electoral law.

Gone is the controversial one-person-one-vote system. Now, there is a list-based system in place, which is designed to encourage the creation of strong political parties.

Voters can now choose candidates from a pre-set list (there are 226 in total), or they can choose the list in its entirety. This is supposed to foster organization and cohesion between candidates, and therefore creating stronger ideological platforms and parties in Parliament.

It’s a new system, and whether or not it will work remains to be seen.

Getting out there and observing Election Day was exactly what JHR trainer, Mohammed, and I did today.

We set out to see a couple of polling centres and talk to volunteers and voters about the election.

Voting takes place at public schools, similar to at home, and polls are open until 7 p.m. local time.

Though people have all day to vote, the results aren’t expected until tomorrow at the earliest.

We stopped at a centre in downtown Amman, and volunteers in bright vests and all kinds of colours flooded the streets. They stood outside of the main entrances, passing out flyers as people entered to vote.

They took turns standing in the street to stop cars, trying to influence the occupants to vote for whatever party they support. Even kids as young as 8-years-old are out volunteering, stacks of flyers in hand.

I spoke to a young volunteer who’s supporting an independent candidate. I asked him what matters most during this election, and like many people have said, access to work and job creation are top of mind.

He’s studying to be a doctor, but wants to ensure he’s able to get a job when he’s finished with his studies.

Many of his friends feel the same way, as Jordan’s youth unemployment rate is one of the highest in the world.

We crossed the street to speak with another group of volunteers, working for a completely different “party.”

The four men hurriedly looked through a long list of names and phone numbers – family and community members who’d promised a vote for their candidate. Each group seems to have a checklist to go through, making sure promised votes are actually secured.

As mentioned, it’s all about patronage.

At another voting centre on the other side of town, two men were yelling in the streets just beyond the voting gate.

Election hustle and bustle outside a voting centre. Polls close at 7pm pic.twitter.com/5XakauZSe2

— Kaleigh Ambrose (@kaleigh_marie_) September 20, 2016

I asked Mohammed what it was about.

One man had promised another that five of his family members would show up to vote. Apparently they hadn’t. He kept shouting “you promised they’d come and vote, where are they? We need them here now.”

It was an interesting up close and personal look into how these elections really take place.

Next up was a look at how local media cover an election. We stopped by Al Balad Radio, a community-based station live-streaming the election.

They have several journalists set up in Amman as correspondents, calling in with up-to-the-minute information, news, and updates. They found that there haven’t been as many people out voting as they thought there would be, but official numbers will likely be released tomorrow.

The last stop of the day was a press conference held by the Integrity Coalition for Election Observation.

They hold several pressers a day about election violations taking place, with observers at every polling centre across the country.

It was interesting to learn that all kinds of violations were taking place as the presser went on.

For example, one observer was kicked out of the polling station without reason.

At another, people loudly declared who they were voting for, as they stamped their thumbs in ink to vote – an election violation.

There were also a few chaotic scenes with people shooting guns into the air, causing trouble and demonstrating in the way they felt necessary.

Finally, some centres were poorly set up for people with disabilities, and one man in a wheelchair had to be carried up the stairs in order to cast his vote.

It sounds cliché to say, but only time will tell what comes of these new election rules and this vote in general.

We’ll see what happens with the results in the coming days!

Day 14

I sat down in a bright yellow chair next to a table of four girls working on their beaded necklaces and decorative straps for glasses, all smiling and talking amongst themselves.

One girl, 19-year-old Samar, immediately exclaimed in English that she’s been to the United States and Italy, when I mentioned I was visiting from Canada.

We both shared a laugh, as she meticulously went back to sorting her coloured beads.

Today, JHR trainer, Mohammed, and I were invited to visit the Jasmine Society for Children with Down syndrome.

It’s a learning centre in Amman, Jordan, that’s trying to change the way people look at and treat kids with an extra chromosome.

In Jordan, many of them face hardships from the moment they’re brought into this world, but the foundation is trying to curb their struggle and develop their abilities into adulthood, through education and a variety of catered activities.

“Teach me, and I will learn,” is the message they try to get across, and the work I witnessed at the centre exemplifies that to a t.

Awatef Abu Alroub started the foundation in 2011, in honour of her own daughter with Down syndrome, Jasmine.

It functions just like a school and a charity in one – parents drop their kids off in the morning and pick them up again in the afternoon, or they ride home in the company van.

The families of the children attending the school provide much of the furniture and supplies – a set of chairs from one family, a desk from another.

“It’s a mix between learning and playing with them, to make sure that they’re learning. I love them all. Children with Down syndrome are very, very kind, and they can learn like [anyone],” said Riham Tarifi, a special education teacher at the centre.

Classes run all week from Sunday through Thursday, with each day sectioned off for a different developmental activity.

Sundays are for reading and writing – many of the kids are already great at both.

Today, Wednesday, was supposed to be athletics, but the sports facilities were being used.

So instead, it turned into arts and crafts day, an important activity to develop motor skills.

Tomorrow, Thursday, is a favourite. It’s focused on housekeeping and life skills, such as cooking simple meals of macaroni, or baking cookies, etc.

Back at the arts and crafts tables, the students proudly showed off their exceptional projects.

Yazan, who’s 36, is an expert with origami. He proudly pointed to his work with his inked finger, having participated in the election yesterday.

He’s a leader in the class, excelling in all areas that he tries, even planning to help teach his fellow classmates how to make paper cranes and other things, just like him.

He does, however, wish he had more opportunities when it comes to education.

“I would like to study in the university like others,” he said in Arabic.

He wants his friends to have the opportunity to grow as well.

“I’d like to change something in my life, like bring computers to our organization and let my brothers and sisters learn,” he said with a smile.

The Jasmine Society is focused on early intervention and preparation for kids with Down syndrome to enter into the mainstream schooling system, should they wish.

But it’s not always possible.

“We have a problem…[these children] are more than others can imagine, full of love, full of positive energy, [but] there is no awareness toward their rights,” said Linda Jaber, a special education teacher who’s been working at the Jasmine Society for 2 years.

There are a number of barriers in place, preventing access to education for this group of overlooked children.

Many public schools don’t have the right tools or funding for special needs programs, and private schools are often financially out of reach.

For example, the normal fee for a private school ranges in the 1050 Jordanian Dinars (JOD) mark per season, so 2100 JOD for the school year.

Mention that your child has Down syndrome, and that number more than doubles to 3000 JOD per season, or 6000 JOD for the year, because of the need to provide a specialized teacher.

If a child with Down syndrome is accepted into the private school program, they’re interviewed and evaluated to see if they’re a good fit, and some are outright rejected.

While laws are theoretically in place to help foster this right to education, the implementation of them is another story that needs working on.

That’s where the Jasmine Society comes in, by trying to provide a classic educational system to give everyone a fair chance to learn.

In the meantime, though, the classmates at the centre are happy to be learning together, and to be a part of something special.

“I like being here with my friends. I love them all, I’m making accessories, hand-made,” says Hiba, a 32-year-old in the adult class.

“I am so happy with my friends,” said Hala, an energetic 13-year-old in the program.

“I love music. I love singing Fayrouz,” says Sahar, speaking about a famous Lebanese singer.

Suddenly, Sahar breaks into song, with people joining in from start to finish.

Perhaps in the not-so-distant future, she’ll have the chance at a singing career of her own.

With the help of the Jasmine Society, she won’t miss a beat.

Day 15

Today was another day of firsts for me in Amman.

Mohammed Shamma and I had been corresponding with Chris Hull, the Canadian Counsellor responsible for political affairs in Jordan.

We met him at a hotel that was hosting an EU conference, discussing the not-yet-fully-revealed election results.

The three of us discussed the CTV and JHR partnership, as well as the work being done in Amman.

Political matters and journalism aside, I also found time to joke about the unique Canadian Embassy barbed wire.

Instead of your average metal barbed wire, I noticed recently that ours has green leaves all over it. It just felt quintessentially Canadian – and we all shared a laugh about that.

Legal Aid in Jordan

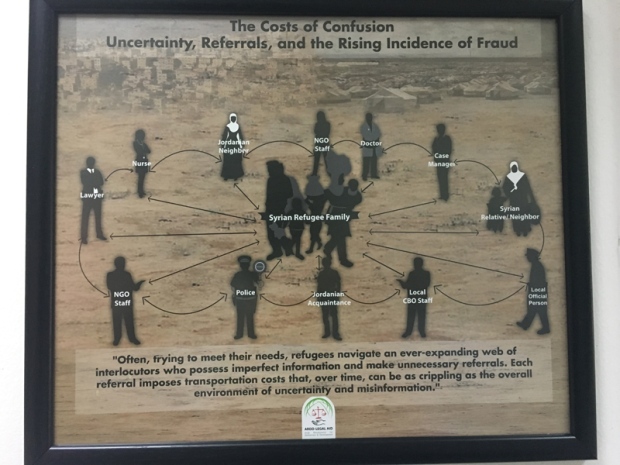

Across the street from the conference stands the Arab Renaissance for Democracy and Development (AARD) Legal Aid office.

We sat down with Lana Ghawi Zananiri, the Gender and Media Unit Manager, as well as Samar Muhareb, the Director.

Their mission is to empower marginalized groups to acquire and enjoy all the freedoms and universal rights, while teaching these groups how to use the law to empower themselves.

The NGO was founded in 2008 and now runs out of nine different offices across Jordan, including in the Zaatari and Azraq Refugee Camps.

Having just been to Azraq a few days ago, it was a fascinating conversation about the work that’s being done on the ground there.

Ghawi Zananiri explained that Jordan’s government, and the people, weren’t expecting the refugee crisis to last as long as it has. It therefore requires the need for a short term, but also a long-term solution, and that’s where ARDD-Legal Aid is trying to help.

“In order to access change, you need to be able to access your rights and know them,” Ghawi Zananiri said. “A big part of our work is on advocacy and how to change the way people think.”

And it’s not just the way Jordanians think, it’s also about empowering refugees to know that they too have rights and can seek the kind of aid being provided by ARRD.

They’re working on civic engagement for women at the camps, ways of identifying problems with the family structure, and working with men and boys on being supportive for women.

When it comes down to it, the whole dynamics of the country have changed with the refugee crisis.

One third of the population in Jordan is a refugee of some kind, according to the World Bank.

That figure isn’t just from the camps, but from the entire fabric of the country as a whole.

Jordan has become a place of refuge for so many, with the average stay of a refugee around 18 years – meaning they aren’t here for the short-term, so short-term thinking and solutions won’t work.

“The challenges and necessities [for these families] have changed over the years. It started as a basic humanitarian [issue], necessities like bread. After a few years, it’s ‘oh what’s going to happen to our health and kids’ education,’ explained Samar Muhareb, the Director with ARDD.

When families realize they won’t be in a camp for only a year, or a few months, their mindset starts to change.

“At year five, it’s ‘oh, how am I going to work,’ said Muhareb.

The challenges for Jordan as a whole have also increased and changed over time.

Whether it be the need for more in-depth strategic planning, a different response plan, dealing with the diminishing of funds, or trying to figure out how to incorporate Syrians into society.

The focus is shifting to integration, and ARDD hopes to help, but Muhareb realizes it’s going to be a lengthy process.

“It’s not something that happens in a day.”

Election

Something else that doesn’t happen in a day – election results – but that was expected.

While results continue to trickle in, they have been announced in a few key districts.

The focus for many, though, is on low voter turnout – roughly 35 per cent of eligible voters showed up to the polls to cast their ballot, according to officials.

When Jordanians went to the polls in 2013, the last Parliamentary election, the turnout hovered around 56 per cent, making this year’s turnout one of the lowest in a generation.

For such an historic election, it’s clear that voter apathy is an ongoing issue in Jordan.

Based on my conversations throughout my time here – at the workshops with journalists, as well as everyday conversations on the street – it’s clear that something has to change.

Time will tell how this election will play out for Jordanians, and we’ll just have to wait and see as the official results continue to trickle in.

Day 16

When I first learned that I’d be heading to Jordan for a month-long adventure in September, everyone kept telling me the same thing: the Jordanian people are as nice as they come.

It was something I knew I’d have to experience on my own to believe, but trust me when I say this, it’s truer than true.

Friday is a weekend here in Jordan. Despite a few stories on the go, everyone is enjoying their weekend, which meant today was a day off for me as well.

I set out for downtown to visit the Roman Amphitheatre (once again), because it’s positively fascinating how much history stands on this land.

I perfected the art of crossing the street and entered a few stores here and there, when an antique shop caught my eye.

For anyone that knows me, antiques are my thing. They tell such interesting stories and I have more than a few decorating my condo – I guess I really am my mother’s daughter.

I picked up a few things, but what I wasn’t expecting was the hospitality and conversation that ensued.

The storeowner and his son had a family friend visiting, and I was invited in for tea or coffee, while I looked around.

The shop was filled to the brim with knick-knacks, in all kinds of silver and gold, and hundreds of beaded necklaces hung from every inch of the corner store.

We talked about Canada, as the storeowner proudly pulled out a special commemorative box from his desk – it was a set of real silver coins from the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

Though I only stayed for 20 minutes, it’s just one example of how friendly the Jordanian people really are, and how proud they are to share in anything that links us together.

When I finished with my downtown adventure, I received an email from one of the participants from the workshop, Abdallah.

He’s been working at the Media Centre throughout the elections and wanted to let me know that he put what he learned in the workshop to good use.

He created a three-part graph, which he included in a report on the election results.

The participants of the workshop have even created a Facebook group to share their work and ask questions, and Abdallah said he received great feedback from many of them.

My time in Jordan is winding down, and I really feel as though the memories and experiences here will shape me for the rest of my life.

It’s reassuring to know that I’ve made an impact; in the same positive way this place will leave a lasting impression on me.

Day 17

Part of the beauty of being in a foreign country and experiencing things on your own is that you are constantly learning.

Whether it be learning about yourself, your comfort level, or even your surroundings, there’s a constant stream of knowledge every turn you make.

My experience in Jordan has been no different.

Today, we met with Leen Khayat, a human rights lawyer in Amman. She specializes in women’s rights, freedom of expression, and has a wealth of knowledge regarding the Syrian refugee crisis.

I wasn’t expecting to learn everything that I did today.

Having visited Azraq and seen firsthand the kind of living situation that exists there, Khalat let me in on another huge issue surrounding the Syrian refugee crisis – child marriages.

“In Syrian culture, it’s okay for young girls to marry an older man, it’s common,” she explained. “They raise their girls to become a mother and a wife.”

In addition to traditions, Khalat explained that marrying girls off at a young age is just one of many desperate attempts to ease the financial pressure and burden on cash-strapped refugee families or provide a sense of security for their daughters. It’s all part of the vicious cycle of poverty.

“As displacement and the challenges of living in exile are weakening other coping mechanisms…families may be more inclined than before to resort to child marriage in response to economic pressures or to provide a sense of security for their daughters,” as cited in a 2014 UNICEF report on early marriages in Jordan.

It’s also sometimes seen as a way for a Syrian daughter to receive sponsorship and reside outside of the camps, if she marries a Jordanian man.

Child marriages, Khalat explained, existed before the war, but were nowhere near as common as they’ve now become.

Early marriages represented roughly 35 per cent of all marriages in 2015 among Syrian refugees, according to statistics from the Chief Islamic Justice Department. That number is almost double the 18 per cent figure in 2012.

“This isn’t weird in the Syrian culture,” Khalat explained. “Marriage after the [war] has many definitions. It’s economic, it’s social, its’ sexual, and it’s a business.”

Khalat went on to explain one of the many cases that has come across her desk as a human rights lawyer.

A 13-year-old Syrian girl was forced to marry an 18-year-old man. They were able to leave the refugee camp, but it wasn’t any kind of idyllic life for this young girl.

She eventually managed to escape her husband after a couple of years, but being on her own meant she struggled financially.

She found that her only solution was to turn to prostitution.

“When she suffered from a harsh sexual treatment, the police took her to the hospital and [an] investigation started,” Khalat explained.

While there are a variety of programs in place within the refugee camps to curb child marriages and raise awareness of rights, as well as doctors trained in hospitals to look for signs of rape, the problem continues to grow for these Syrian refugees.

While the minimum age for marriage is 18 in Jordan, certain circumstances under Sharia law allow judges to authorize younger marriages.

The laws are in place, but not always implemented.

“We are dealing with the problems, but can’t find the solution,” Khalat explained.

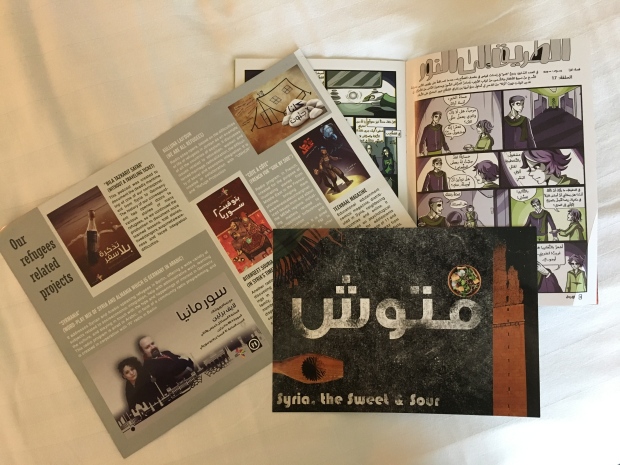

These are the same issues that Syrian radio station, Souriali, is trying to shed light on.

We visited their offices in Amman, after a failed attempt at speaking to a doctor who deals with child marriages and rape cases, at a downtown hospital.

Souriali is a social radio station, trying to bring awareness to issues facing Syrians all over the world.

“We talk about issues related to Syria, from Syrians,” explained Hassan Muhra, the head of production for Souriali in Amman.

For example, when discussing a ceasefire in Aleppo, the focus isn’t on the details of the ceasefire or how it works.

Instead, Souriali looks at how the lives of the Syrian people are affected, and what it means for the actual human beings on the ground.

They broadcast from a number of cities, with correspondents stationed all over the world – from Europe to Syria to Jordan.

I later found out that one of the participants from my workshop is actually a broadcaster here with her very own radio show.

The station relies not only on trained journalists, but citizen journalists in countries abroad, with social media playing a vital role in each broadcast.

All production can be downloaded from their website, heard on their smart phone application, or accessed on Sound Cloud and YouTube.

Though Internet connections are sparse on the ground in Syria, there are a few undercover places to access Internet in the regime-controlled cities.

For Syrians living outside of Syria, they have a variety of shows aimed at the lives of Syrians abroad.

Some shows include discussing how to build a genuine Syrian identity while living away from home, staying culturally connected, the difficult lives of asylum seekers or refugees, the deadly journey from Syria to Europe by sea, and many more.

The main goal, as their slogan states, is to “give a voice to the voiceless.”

Based on my short visit, their efforts do not go unnoticed.

Today came together in an unexpected way.

Every day in Jordan, I’ve been able to learn something new about the people, the culture, the lives, and the country itself.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to not only learn for myself, but also share my experiences with others.

Though I’ve only begun to scratch the surface in my few weeks here in Jordan, I’ll take back an invaluable amount of knowledge, and a newfound way of looking at the world.

Day 18

For the first time in Jordan, I awoke to news with no positive spin in sight.

This morning, before I’d even eaten breakfast, prominent Jordanian writer, Nahed Hattar, was shot dead outside the courthouse in Amman.

It happened just five minutes away from my hotel.

Hattar was set to go to trial for a Facebook posting he’d made earlier this summer. It was a cartoon caricature that was deemed offensive to Islam.

The posting depicted a bearded man in heaven, surrounded by women, asking God to bring him cashews and wine.

The Christian writer posted the cartoon to Facebook, but received intense backlash, and later took it down, saying it was meant to show the extreme religious views of ISIS members.

The damage was done though.

Hattar showed up for his trial today, and was shot in the head by what authorities are calling a man with extremist views.