TORONTO -- As back-to-school season ramps up across Canada, the federal government is being urged to do more to help children in rural and remote parts of the country, including Indigenous communities.

The deputy grand chief of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), which represents 49 First Nations in northern Ontario, told CTV's Your Morning on Thursday that the 9,000 elementary- and high-school-aged children in those communities are facing difficulties from the isolation brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

"They, like many of us, are struggling with mental health and just excited to get back to school, get back to seeing their friends," Derek Fox said from Thunder Bay, Ont.

However, getting back to school may not be as feasible in northern Ontario as it is in southern parts of the country. Two schools in NAN communities have pushed back their reopening dates until October, and Fox said others are "definitely at risk of closing indefinitely."

The issue, he said, is a lack of funding for measures to fight the spread of novel coronavirus in the schools. NAN has asked the federal government for $33 million to cover additional costs for teachers, nurses and mental health support workers, as well as personal protective equipment, sanitation materials and more.

The government promised last week to help schools reopen safely, but drew criticism from NAN for not offering specific details of what that help will entail.

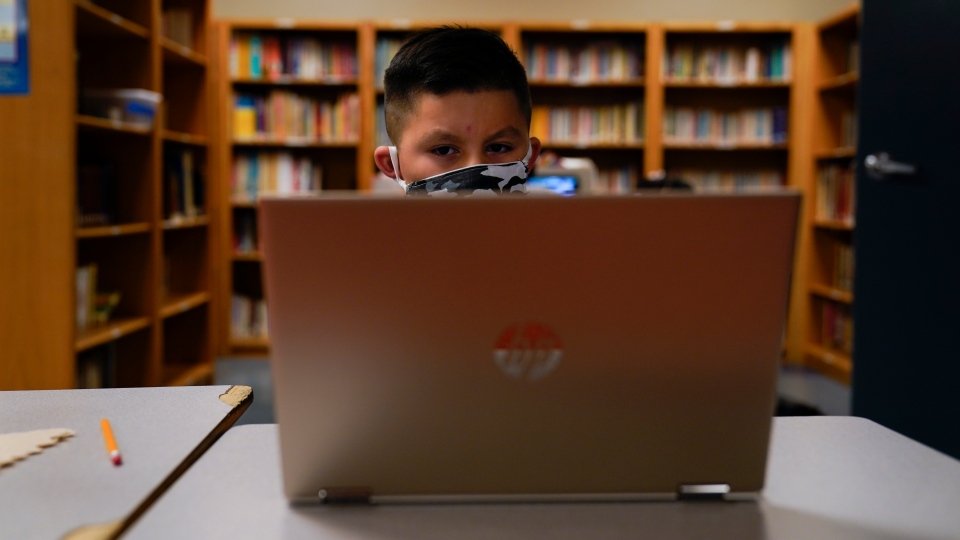

Online learning, which has become the norm in more populated parts of Canada when in-person classes are not achievable or desired, is not a viable option across the North. Fox said that 32 of NAN's 49 communities do not have access to high-speed broadband internet – making video instruction and other digital education tools inaccessible.

"The ability of our students to connect to online [learning] – they're going to have a hard time doing that," he said.

Lack of broadband service is a widespread issue in rural and remote parts of Canada. According to the most recent statistics from the CRTC, 40.8 per cent of rural households and 31.3 per cent of Indigenous reserves had access to high-speed internet as of 2018.

"[Those numbers are] a lot greater than I think some of us in urban areas realize," Laura Tribe, executive director of internet accessibility advocacy group OpenMedia, said Thursday on CTV's Your Morning.

Moreover, having the infrastructure in place doesn't mean the service is actually being used. Because Indigenous communities experience higher rates of poverty, some households on reserves may not be able to afford high-speed internet service.

Many school boards are loaning computers or tablets to students who do not have their own. Tribe said this is a step toward internet equity, but of little help in households that do not have broadband access.

With many families "already doing everything that they can" to help children continue their education through the pandemic, she said, the best solution is for immediate government action to ensure all students are able to take advantage of learn-from-home options.

"What we really need is for governments … to actually step up and make sure that those students are not left behind," she said.

The federal government announced last year that it would spend $6 billion to connect every home in Canada to broadband internet by 2030, when a child entering junior kindergarten this fall would be starting high school.