TORONTO -- Jimmy Cloutier was shot and killed by police in Montreal on Jan. 6, 2017.

Rodney Levi was shot and killed by police in Miramichi, N.B. on June 12, 2020.

Cloutier, 38 and white, was a longtime client of a homeless shelter. An investigation by Quebec's police watchdog found that police shot him after he stabbed another man and ran toward a police officer with a knife in his hand.

Levi, 48 and Indigenous, has been described as nonviolent and dealing with mental health challenges. Police have said he had threatened officers and was in possession of two knives. Quebec's watchdog has been brought in to investigate his death, too, because New Brunswick does not have a similar agency of its own.

In the time between their deaths, 98 other people were fatally shot by police officers in Canada – a rate of approximately one death every 12.6 days.

The stories of Cloutier and Levi are in many ways representative of those of the other 98, according to a CTV News analysis.

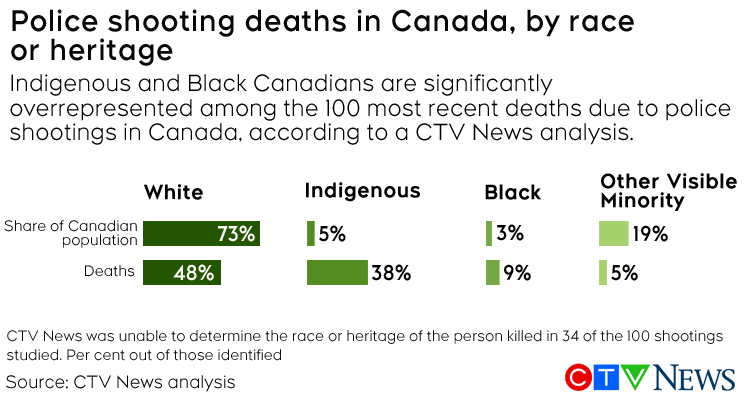

Of the 100 people most recently shot and killed by police officers in Canada, nearly all are male. Most are either white or Indigenous, although when population size is taken into account, Indigenous and Black Canadians are far more likely to die in a police shooting than white Canadians.

Norm Taylor, who was part of an expert panel that compiled a report on Indigenous policing for the federal government last year, described the overrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in the analysis as "staggering" but expected.

"I don't think that's a surprise to anybody, but it's always shocking when you see it," he told CTVNews.ca via telephone June 17 from Oshawa, Ont.

There is one other aspect of the deaths of Cloutier and Levi that accurately reflects the other fatal shootings. Out of the 100 cases studied by CTV News, only one resulted in charges being laid against police. In the other 99 shootings, either the officers involved were cleared of wrongdoing or the events remain under investigation.

Those who have studied the issue closely warn that focusing too heavily on the actions that immediately led to the shooting misses the systemic issues that brought the situation to a point of no return.

"It's very easy to get people fired up over an incident that went bad and avoid the conversation of 'Why do these incidents keep happening?'" said Taylor, an executive adviser who has worked with many police executives and several provincial governments on issues around policing and public safety,

"It will usually turn out to be a tragic situation that went from bad to worse, and very limited options were ever really in play."

THE ANALYSIS

Finding information on fatal police shootings in Canada is not a simple task. There is no centralized database that records these deaths at the national level, in part because there is no one body that oversees police officers across the country.

In seven provinces, records of police shootings can be found through agencies that have been set up to investigate deaths involving police interactions and allegations of officer malfeasance. Jurisdictions that do not have these organizations – Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and the territories – may call on one of these provincial bodies, or another police service, to look into similar cases.

CTV News searched the records of these oversight bodies and found 100 cases since 2017 in which a person died after being shot by police and suicide has not been determined to be the most likely cause of death.

We then used police and media reports to attempt to determine the name, age, sex and race of each person shot and killed by police, as well as the location where the shooting happened and the status of the investigation into the role police played in the death. Not all pieces of information could be found for every death.

THE FINDINGS

The analysis shows that 92 of the 100 people shot dead by police officers in Canada since the beginning of 2017 were men, and eight were women.

In addition to being disproportionately male, the group is disproportionately young. More than half of all those killed were between the ages of 20 and 34, even though that demographic accounted for less than 20 per cent of Canada's overall population in the 2016 census.

Even greater discrepancies are found when it comes to race and heritage. Of the 100 cases studied, 28 involved deaths of people whose identities have never been made public, making it impossible to determine their background. There were another six cases where names have been released, but race and heritage could not be ascertained from the publicly available information.

This leaves 66 deaths, 32 of which involved white Canadians. There were 25 deaths involving Indigenous Peoples, six involving Black Canadians and three involving Canadians belonging to other visible minority groups.

When comparing those numbers to the overall population, though, it is apparent that Indigenous and Black Canadians are far more likely to be killed by police than any others.

"It's clear that First Nations people continue to be hurt or die at the hands of police," Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde told CTVNews.ca via telephone on June 17 from Ottawa.

"It's dreadful and it's alarming that ... the trend is not going down -- in fact, it's increasing."

Based on census demographic data from 2016, the 25 Indigenous deaths represent a rate of 1.5 out of every 100,000 Indigenous Peoples being shot and killed by police, and the six Black deaths represent a rate of 0.5 out of every 100,000.

Both those numbers are well above the overall Canadian rate of being shot and killed by police, which is 0.3 per 100,000 and far higher than the rate for white Canadians, which is 0.13 per 100,000.

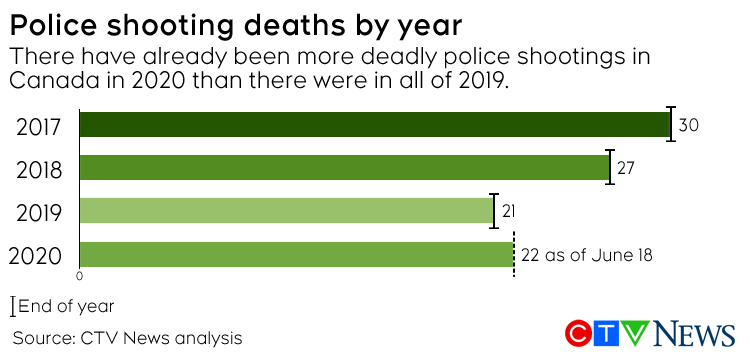

The data also makes it clear that 2020 is an especially active year for fatal police shootings. Levi's death was the 22nd such shooting of the year – more than the 21 recorded in all of 2019, based on our records.

THE INVESTIGATIONS

Each of the 100 police shooting deaths studied here was quickly subjected to an investigation conducted by either the ruling provincial watchdog or – in the places where there is no such organization – an agency from another jurisdiction.

The amount of time it takes to complete an investigation into a police-involved death varies significantly based on factors including the circumstances of the death and the agency tasked with looking into it.

Fatal shootings are among the most complicated of these investigations, and are rarely wrapped up within a few months. Sometimes they take years; three of the 30 shootings from 2017 are still under investigation.

CTV News found that investigations are still ongoing into 46 of the 100 deaths examined. In 53 cases, the reviews concluded that police acted reasonably under the circumstances, fearing what would happen to their lives or the lives of others if they did not shoot.

Only one death – that of Clayton Crawford near Whitecourt, Alta. in July 2018 – resulted in charges being laid. After a nearly two-year investigation by the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT), two RCMP officers were charged earlier this month with criminal negligence causing death.

According to ASIRT's report, an off-duty RCMP officer found Crawford asleep in a vehicle at a rest stop near Whitecourt. The officer believed the vehicle was the "distinctive" one police were looking for in connection with a shooting the previous day in Valhalla Centre, Alta., more than 300 kilometres away.

The off-duty officer reported his suspicion to his working colleagues. When they approached the vehicle, ASIRT found, there was a confrontation and Crawford tried to drive away. Two officers fired at the vehicle, which soon crashed. Crawford, who had been hit by more than one shot, died.

It is not clear why the Crown believes the actions of the officers amount to criminal negligence causing death, and the allegations against the officers have not been tested in court. Both officers were on active duty before the charges were laid but have since been suspended with pay.

When the charges were announced, ASIRT's executive director said it was the first time in the organization's history that a deadly police shooting had led to a criminal case against police officers.

Edited by CTVNews.ca senior producer Mary Nersessian; infographics by Mahima Singh

Backstory:

CTV News searched the records of police oversight bodies in the seven provinces where they exist, as well as press releases from police agencies in the other three provinces and the territories, to compile a list of 482 cases since 2017 in which a person died during or around the time of an interaction with police.

It is unlikely that the 482 cases we found represent every instance of a person dying around the time of a police encounter. Provinces and territories can set their own rules for reporting these deaths to the public. Some watchdog agencies provide basic details about every such death, while others have stricter criteria for releasing information.

Of the 482 deaths in our records, there were exactly 100 in which the person who died was shot by police and suicide has not been determined to be the most likely cause of death.

Searching through police and media reports related to those 100 deaths, we attempted to determine the name, age, sex, race and heritage of each person shot and killed by police, as well as the location where the shooting happened and the status of the investigation into the role police played in the death.

Not all pieces of data could be found for all shootings, in part because of further differences in how certain provinces report police-involved deaths.

In Quebec, the Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes releases the name and age of every individual killed during a police interaction. This is not standard practice at any of the other oversight agencies, although names are sometimes released by authorities outside Quebec if the family of the person killed gives consent.

The heads of the agencies outside Quebec have argued that keeping names of citizens involved in its investigations private is a matter of "compassion and human decency," and that publicizing names can make investigations more difficult.