Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne is speaking out against a proposal from a teacher’s union to rename schools in the province dedicated to Sir John A. Macdonald, saying the organization “missed the mark.”

Wynne said in a statement Thursday that Canada’s first prime minister was “far from perfect” and that his government’s decision to open the country’s first residential school was “among the most problematic in our history.”

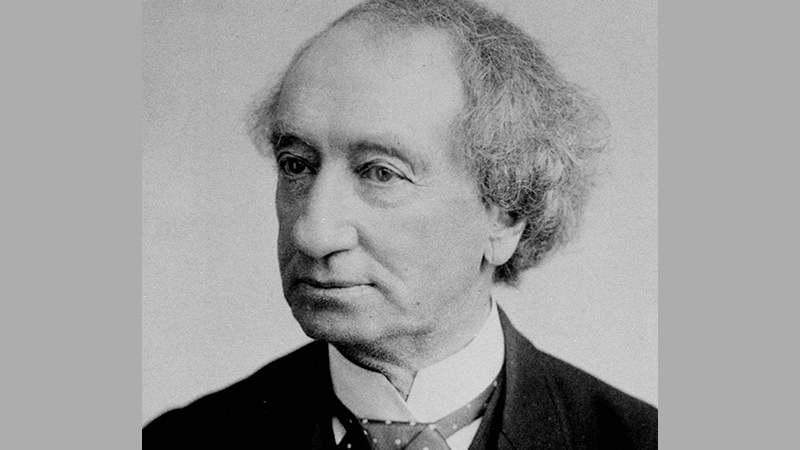

But Wynne declared Macdonald a “father of confederation” who “contributed greatly to the creation of a stable federal government for Canada.”

“The more important question we should be asking ourselves as we move forward is how do we enact meaningful reconciliation with our indigenous peoples?” Wynne said.

“We need to teach our children the full history of this country -- including colonialism, our indigenous peoples and their history and about what our founders did to create Canada and make it the country it is today. We need to understand our history, the good along with the bad, so we can move forward in an era of mutual respect and understanding with our indigenous peoples.”

The premier’s comments come after the Elementary Teachers' Federation of Ontario passed a motion last week to urge all school districts to rename schools and buildings bearing Macdonald’s name, calling him an "architect of genocide against Indigenous Peoples."

The union also cited Macdonald’s involvement as Canada’s prime minister when the federal government approved the country’s very first residential school.

Mi’kmaw woman and Halifax poet laureate Rebecca Thomas heralded the decision and said she welcomed the idea of going further to remove Macdonald’s face from Canada’s $10 bill.

“It was Sir John A. Macdonald who said that you needed to separate kids from their parents or otherwise you’re just going to have an educated savage that can read and write,” Thomas told CTV News Channel on Thursday.

“We don’t need to venerate and honour these individuals any longer.”

The proposed renaming may trigger an “uncomfortable feeling,” Thomas says, that forces Canadians to grapple with the way founders treated Indigenous people.

In 1883, Macdonald stood before the House of Commons and voiced his support for residential schools, saying that Indigenous children who went to school “on the reserve” would still be “surrounded by savages.”

"Though he may learn to read and write he is simply a savage who can read and write. Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence," Macdonald said.

Residential schools remain one of the darkest policies ever passed in Canada. Thousands of students died in the schools, and cases of sexual and physical abuse were rampant.

It wasn’t until 1996 that Canada’s last federally-run residential school closed its doors.

Removing Macdonald’s name from schools and other institutions wouldn’t be a form of erasure, Thomas says, but of reconciliation.

“I think it’s important to recognize that the history of Canada was built out of violence and it was built out of taking something away from indigenous people and it was built on things such as residential schools. And it’s an important part of our history with reconciliation to stop honouring people who were active players in that history,” she said.

Similar controversies have sprung up recently across Canada.

In Halifax, Mi’kmaw groups have called for the city to remove a bronze statue of Edward Cornwallis, who founded Halifax in 1749 and later called for a bounty on Mi’kmaw scalps.

In Toronto, two students groups called on Ryerson University to change its name. The school’s namesake, Egerton Ryerson, is considered one of the architects of residential school policy.

Debates over Confederate statues and monuments across the American South have been amplified in recent weeks since a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va. Statues depicting

Confederate leaders have since been removed in Maryland and North Carolina.

In Charlottesville, two statues of Confederate generals were shrouded in black on Wednesday.

With files from the Canadian Press and the Associated Press