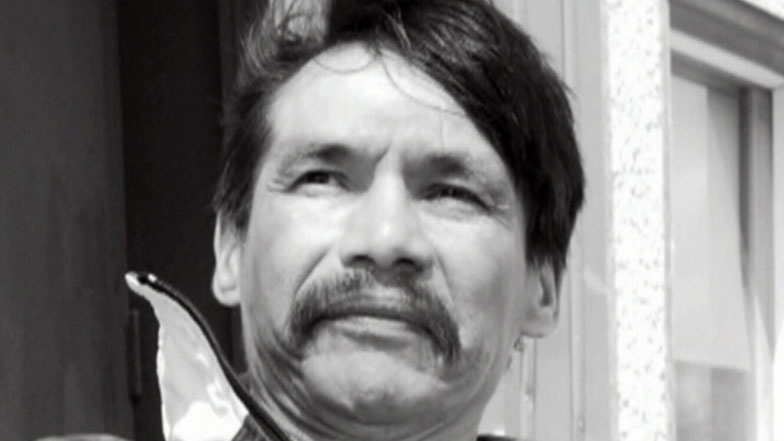

WINNIPEG -- No aboriginal services staff was working the weekend a First Nations man died during a 34-hour wait at a Winnipeg emergency room.

Aboriginal services worker Matilda Patrick told an inquest into the death of Brian Sinclair that no one in her department works weekends at Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre.

Patrick, who acts as a liaison between aboriginal patients and staff, said she worked with Sinclair in 2007 when he lost both his legs to frostbite after being found frozen to church steps in the dead of winter.

At the time, she said he was quiet and worried about where he was going to live when he was discharged from the hospital.

"He was very soft-spoken. At times, it was hard to hear him talk but I understood what he was saying," she said Wednesday. "He asked to speak to a social worker."

Patrick said she wasn't told when Sinclair was discharged, nor is she always informed when an aboriginal patient is admitted to hospital. She said she found out about Sinclair's death in September 2008 from the media.

Sinclair was referred to hospital on Friday, Sept. 19, 2008 by a clinic doctor because he hadn't urinated in 24 hours. The double-amputee is seen on security footage wheeling himself into the hospital emergency department and speaking to a triage aide.

After the triage aide writes something down on a pad of paper, Sinclair is seen wheeling himself into the waiting room where he was discovered dead 34 hours later. While he waited, Sinclair vomited several times and was given a bowl but was never examined by medical staff.

By the time he was discovered, rigor mortis had set in.

Sinclair died of a treatable bladder infection caused by a blocked catheter.

Patrick said she learned the hard way never to wake a sleeping patient because they are usually unco-operative. It was common to see people take shelter in the emergency room, she said.

"Sometimes, patients will come in beaten up or intoxicated," Patrick said. "They just let the person sleep it off and then discharge them. At first it bothered me a bit that the patient knows they shouldn't drink when it's cold outside. But it would bother anyone, not just me."

She told inquest judge Tim Preston he should recommend aboriginal services be staffed seven days a week.

Beverly Swan, regional discharge planner for the health authority's aboriginal services department, said her department also doesn't work weekends. Although someone from her department attends daily rounds in the emergency room, Swan said that only occurs Monday to Friday.

Swan, who worked with Sinclair when he lost his legs in 2007, told the inquest Sinclair was upset at the time about the housing he was given. It was too noisy and there was a lot of drinking, Swan said.

Sinclair got agitated talking about it and struck Swan on the arm, she said.

"He wanted to get out of that lifestyle," Swan said. "He told me he didn't want to go back to that lifestyle. He pointed to his legs and said 'that's why I'm like this."'

She told the judge that policies and recommendations from an inquest won't address all the systemic issues facing aboriginals within the health care system.

"It does not change an individual's perception of another individual," she said.

The inquest also heard from a patient who was triaged around the same time Sinclair arrived at the hospital. Kathy Boddy said she remembered Sinclair from the waiting room -- not because he was drawing attention to himself but because he was a double-amputee in a wheelchair.

"I recall him having his head down. I thought he was just resting," she said. "He just stuck in my mind that day."

Boddy said she was told by nursing staff she would likely be waiting a long time for care and ended up leaving without being seen.

"It was really busy," she said. "The waiting room was quite full.

"The inquest continues for the rest of the month and is expected to hear from the couple who first noticed Sinclair was dead and tried to alert security.