Food banks across Canada continue to experience significant challenges due to a rise in demand amid high inflation rates— and 2023 is expected to bring similar woes, organizations have told CTV News.

As the holiday season wraps up, some of these groups are encouraging Canadians to advocate for systemic change to help lift people out of poverty, adding that increasing food bank capacity is not a long-term solution, as food insecurity is linked to overarching issues like income inequality and housing affordability.

“I’ve never experienced a festive season this difficult for us as individuals and as an organization,” said Tamisan Bencz-Knight, manager of strategic relationships and partnerships at Edmonton’s Food Bank, in an interview with CTV News Channel on Monday.

Currently, Edmonton’s Food Bank had to open up drive-through services in minus 40 degrees Celsius conditions due to demand.

“It’s not to say people haven’t been generous….it’s volumes of need,” she said. “Those who were able to make ends meet in previous years now need to rely on food banks.”

The food bank is serving more than 30,000 people each month, which she says are “huge amounts of people” turning to their organization.

Food bank usage is connected with struggling to afford other necessities, such as housing and fuel, she said. Those who used to donate and who are now experiencing the same rise in cost of living are now seeking help from the food bank, she explained.

“Our team has had to stop and walk people through steps they’ve never experienced, from an organization they used to give to,” she said.

Other food banks around Canada have reported the same concerns. The Toronto-based Daily Bread Food Bank and North York Harvest released data in March for their annual Who’s Hungry Report that showed food bank usage from April 2021 to March 2022 had increased 16 per cent year-over year, from 1.45 million to 1.68 million.

The study also found that more than 80 per cent of people who are working are living in deep poverty, which is an income of $19,000 a year or less for a single person.

Those who identified as food insecure in the survey were also disproportionately Black and Indigenous people, which the study links to the longstanding impacts of colonialism and anti-Black racism in Canada’s institutions.According to researched published in 2021 in the Canadian Journal of Public Health, Black people in Canada have 1.88 times the odds of food insecurity compared to white people. The researchers point to how a lifetime of being subjected to structural racism, from multiple realms including education to the workplace, can end up impacting a person’s income.

As well, research from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives also highlights how damage inflicted by colonialism, including the residential school system and genocide, has affected the income of Indigenous people in Canada for generations.

It’s important to understand that hunger is an issue related to income, and donating to food banks may help feed families temporarily but it will not contribute to systemic change, which would include wage increases, said Josh Smee, the executive director of the Newfoundland and Labrador-based non-profit Food First N.L., in an interview with the Canadian Press at the end of November.

And in Vancouver, the Greater Vancouver Food Bank told CTV News Vancouver that it is taking on 1,000 new clients per month, compared to the 400 per month seen last year.

NEEDING REAL SOLUTIONS

"The reality of it is that we've built a system where private charity is filling in for where the social safety net should be," Smee said. “Food itself will not bring people out of poverty.”

However, he encourages those who are donating to food banks to continue to give, but also to reach out to lawmakers or other leaders about social change.

Social assistance rates should match inflation and minimum wage needs to be raised, said Smee.

In Ontario, the minimum wage increased to $15.50 per hour as of Oct. 1. British Columbia also increased minimum wage for workers on June 1 from $15.20 per hour to $15.65. Currently the highest minimum wage is in Nunavut, where people are paid $16 per hour.

But whether the minimum wage amounts to a liveable wage is debatable. According to the Ontario Living Wage Network, those living in the Greater Toronto Area would need to make at least $23.15 an hour to meet basic needs including food and rent. The organization’s living wage estimate doesn’t include paying off debt or having the ability to create savings.

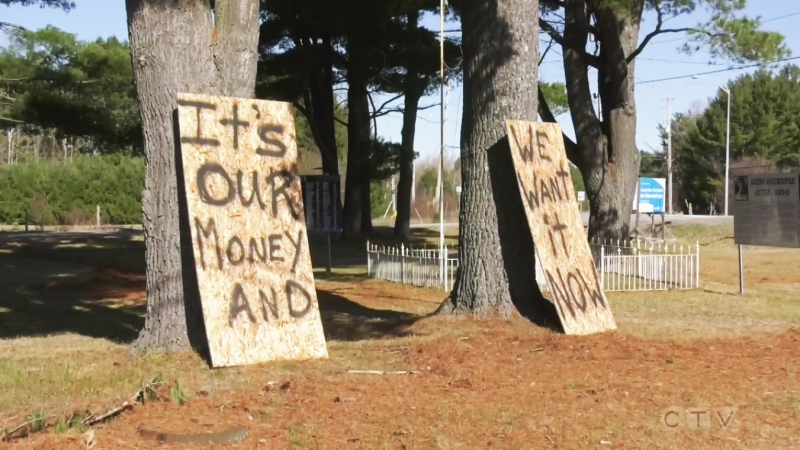

In Nova Scotia, the organization Feed Nova Scotia told CTV News Atlantic on Nov. 28 that the agency is seeing 300 new clients per week.

Executive director Nick Jennery said residents should contact their local government representatives about increasing food insecurity in the province.

He gave an example of a client who needed to use a food bank, but because he lives in a tent, he can’t cook food there.

For more resources, people can use Food Banks Canada’s online tool that allows individuals to find food banks in their area