WINNIPEG -- Manitoba's Court of Appeal has halted an inquiry into the death of a five-year-old girl so that it can hear arguments over whether witness interviews should be fully disclosed.

The inquiry into the death of Phoenix Sinclair has been examining how the girl fell through the cracks of the province's child welfare system. She was beaten to death in 2005 by her mother and mother's boyfriend, months after child welfare workers removed her from a foster home and gave her back to her family.

Several child welfare authorities are fighting a decision by inquiry commissioner Ted Hughes to give them only summaries of the commission's pre-inquiry interviews with the 140 or so witnesses who are to testify. They asked the Court of Appeal to grant them the full transcripts, and on Friday, the court agreed to hear the case.

"In my view, the applicants have raised an issue which is one of importance," Justice Marc Monnin wrote.

"The transcripts appear to be documents of a similar nature to those this court has found to be subject to (mandatory) disclosure under principles of procedural fairness."

Monnin indicated the hearing could take place as early as October, although there was no indication how soon afterward a ruling would be made.

"It may be that we don't start (again) until November or December. It's hard to predict," Sherri Walsh, the lawyer leading the inquiry, told reporters.

Witnesses were told that full transcripts of what they said would not be released, Walsh said, and so they spoke very frankly. Many are social workers who still work in the child welfare system.

"Sometimes people vented about their experiences in the system. Again, that's not something that needs to be disclosed or something that will form part of the subject matter of what we're calling as evidence."

The inquiry has already survived challenges from the union that represents Manitoba social workers. It lost one court battle to limit the inquiry from finding fault and another that would have granted anonymity to social workers who testify. The only witnesses whose names are protected by a publication ban are seven individuals who called police or child welfare agencies with concerns about Phoenix.

The inquiry was only in its third day of hearings and had just begun to hear details of how Phoenix Sinclair was taken from her mother, Samantha Kematch, a few days after her birth.

Kematch had a history of violence and abuse and a complete disinterest in being a parent, but child welfare workers hoped she would eventually regain custody of her daughter, one social worker testified.

"We're a bit in the business of hope and the idea that people can get help for some of the issues that plague them ... that we can help people to be their best and to perhaps give a shot at parenting at some point, with the right supports," Marnie Saunderson told the inquiry.

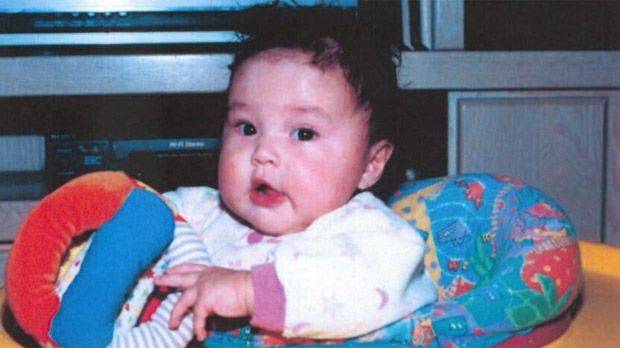

Saunderson was the social worker who seized Phoenix a few days after her birth in April, 2000. She told the inquiry the decision was made in part because of Kematch's troubled past. Kematch had herself been abused by her mother, had run away from foster homes, had hung out with gang members and had stolen cars.

Kematch gave birth to Phoenix at 18, and showed little interest in parenting the girl. She had given birth to a son two years earlier, who had been seized by child and family services. Kematch told another social worker that her son had been taken because workers feared she would hurt him.

Kematch's story was not unusual for someone in the child welfare system, Saunderson testified.

"Often those children turn out to be fairly angry teenagers or people who are struggling with their emotions, and so I would say Ms. Kematch's ... file, sadly, is fairly typical."

Saunderson managed the file for just three days. She discovered she was related to someone involved in the case and declared a conflict of interest. The file was handed over to her supervisor, Andrew Orobko, and would be managed by many different workers over the next four years.

Orobko told the inquiry Friday he met with Kematch and Steve Sinclair, Phoenix's biological father, on May 1st and found Kematch to be withdrawn and unresponsive. She answered complex questions with shrugs and the phrase "I don't know", he said, causing him to wonder if she had psychological problems.

"That's what struck me -- is there some underlying psychological concern here?" Orobko testified.

"Knowing the family history, I was probably thinking 'has there been some undiagnosed fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Is that a possible root cause of what we're seeing here?' I probably would have been querying things like post-traumatic stress disorder."

Orobko drew up a case plan that called for Phoenix to be put in care for at least three months. Kematch and Sinclair were granted weekly visits with Phoenix and Kematch was to undergo a psychological assessment.

The inquiry has yet to delve into a key question: why was Phoenix handed back to Kematch in 2004 and why was her file closed a few months later? In early 2005, a social worker went to check on Phoenix, was told she was asleep and left without seeing her. It was the last time anyone from child and family services attempted to see Phoenix before her death.

Kematch and her boyfriend, Karl McKay, were convicted in 2008 of first-degree murder. According to evidence at their trial, they frequently confined, beat and neglected Phoenix. She was sometimes shot with a BB gun and forced to eat her own vomit.

She died in June, 2005 after a final assault in the basement of the family's home on the Fisher River reserve and was buried in a shallow grave near the community's landfill. It took almost nine months for authorities to discover the death. In the interim, Kematch continued to claim welfare benefits with Phoenix listed as a dependent.

The witnesses who have appeared so far at the inquiry have said the child welfare system has always been strained by heavy workloads. Orobko and Saunderson worked at an agency that served Winnipeg's north end, one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Canada.

"That community in north Winnipeg was afflicted with staggering rates of poverty ... a lack of economic opportunities, illiteracy, an over-preponderance of single-parent households," Orobko said

"The prevalence and the octopus-like grasp that the gangs had in north Winnipeg ... that's our backdrop."

To make matters worse, social workers' caseloads in the area were double or triple the amount suggested as a standard by an American child welfare research group.

"We were being asked to deliver child welfare service in probably the most daunting community in this country with human resources that were grossly insufficient to meet the needs of that community," Orobko told the inquiry.

The Manitoba government has funded 230 new social worker positions since 2006, but the number of children in care continues to rise sharply. There are now roughly 9,000 children in the child welfare system -- almost double the number a decade ago.