TORONTO -- The death of George Floyd in Minnesota has spurred massive protests across the world, including here in Canada, as people tackle the difficult problem of systemic racism and its effects.

While many Canadian leaders have denounced the death of Floyd, a Black man who died in Minneapolis after a white police officer held his knee on Floyd's neck for several minutes, his death has also prompted some to claim that systemic racism doesn't exist in Canada as it does in the U.S.

Canadians who have faced discrimination disagree, saying racial tensions do not stop at the border.

In an effort to address systemic racism in Canada, CTVNews.ca asked readers to share their experiences of discrimination. Here are some of those experiences and reflections on what can be done to combat racism in the country.

CHARLYN NONO

Oakville, Ont. resident Charlyn Nono was shopping with her 18-month-old daughter at Walmart when a code Adam safety alert was called for a missing 7-year-old boy wearing blue. Nono identified as Black however her daughter is mixed race and has very light skin.

“I think that she looks just like me and she calls me mom in public, but when the code Adam was called I was approached by two Walmart employees and they grilled me on whose child I had in my cart,” Nono said in a phone interview on June 4.

Nono told CTVNews.ca that her daughter was wearing a pink dress and had pigtails in her hair saying she was “very obviously not a 7-year-old boy.” Nono said one of the employees even put his hands on her daughter.

“It looked like he was trying to pick her up and take her away from me,” Nono said. “I was infuriated… It was all emotions but the biggest emotion was anger, because why can’t I just go shopping with my own child?”

When asked if they were stopping all mothers with kids in the store, Nono said the employees did not respond.

“Based on [my skin colour] they saw her and automatically assumed that she wasn't mine -- that she wasn't suppose to be with me and that I was doing something wrong,” Nono said. “It was never said but I could feel it implied that because I’m Black and my child looks white I stole her.”

Nono said this was the first time she had been questioned on who she was in relation to her daughter. Since then, she says it has happened multiple times.

“I have had to show my ID more times than I can count. I keep her birth certificate and her health card and her social insurance card on me at all times because I'm stopped by people of authority, not police, but teachers, principals... Even if she's running towards me screaming my name, they don't believe that I'm her mother,” Nono said.

When her daughter was three, Nono said a similar incident happened in a park where she was mistaken as a nanny.

“We were having a picnic [and] another mother came up to me and started to chat. She asked the general conversation starters like my daughter’s name, how old, et cetera. She then proceeded to let me know she’d been watching me and saw how good I was with children and asked me how much it would take to leave my current employer,” Nono said.

“She offered me a job because I looked like this little girl’s nanny.”

Nono said white people in Canada will “never know” what Black people have to go through “in defending [themselves] against ridiculous questions and accusations.”

“I’ve spent the last six years having to explain my background to white people because they can’t believe that a black-skinned woman can have a light-skinned child,” Nono added.

While she hopes anti-racism protests will bring about change in the country, Nono said racism isn’t a new issue.

“My mom has a different skin tone than me and has had these exact same experiences as I'm having now,” she said. “It's not like it's going to change but I'm just hoping that more people can listen and open their minds and know that we're just people. We're not here to do bad things we're just trying to live our lives.”

REN THOMAS

Having lived in the U.S., the U.K. and the Netherlands, Ren Thomas says she has experienced far more racism in those countries than in Canada.

However, the assistant professor at Dalhousie University’s School of Planning told CTVNews.ca that her life has been impacted by racism in various forms: from daily microaggressions to receiving lower scores on teaching evaluations and even being passed over for job opportunities.

“It’s very well documented across the U.S. and Canada that when students evaluate their professors they consistently give higher rankings... to white professors and to male professors, and I've definitely experienced that,” Thomas said in a telephone interview on June 3.

Despite being educated at some of Canada's top schools, Thomas said she has regularly been denied for interviews and jobs at these institutions based on her skin colour.

“It took 13 job interviews over six years to get my current job, while most people I know did two interviews. The University of British Columbia, where I completed my PhD, went 20 years without hiring a woman in the department and only four of their 15 professors are visible minorities,” Thomas said.

Thomas said she has struggled to succeed at white-dominated universities throughout her career, in part because there is no institutional support for visible minority faculty.

“It's pretty discouraging because you know you can never reach that level, you can never get that top job, and you can never accomplish what that person will accomplish in their lifetime, and it's based on something that you have no control over,” Thomas said.

While she said these incidents of racism and others in Canada “are a lot milder” that what has recently happened in the U.S., discrimination is still happening in the country. While she has never felt targeted by the police, she said she knows other people in Halifax who have.

“People do see these incidents as outrageous and I think people identify with them in other countries. And having lived in other countries myself, no place that I've lived has been free of racism,” Thomas said. “We can't rely on governments or institutions to change everything. Sometimes the change has to come from people, it has to come from the ground up.”

Following the protests, Thomas said the next step is for political leaders to change legislation and address requests to defund the police.

“We have to make sure that the police are operating within their own rules and that they're protecting people. In George Floyd’s case, they were really misusing their power and for really no reason, because he wasn't a threat. So I think overhauling some of those procedures, introducing some oversight so that when rules are broken that people are actually punished, that charges are laid, people lose their jobs and there are actual consequences to these actions,” Thomas said.

“Obviously the police, like many first responders have very difficult jobs, but that doesn't excuse them from having to actually act properly and take proper precautions,” she added.

As a professor who is a visible minority, Thomas said she regularly brings her experiences of racism into the classroom and encourages students to do the same to better education everyone in the room.

“I don't know anyone who is not the visible minority in Canada, who hasn't experienced racism and when I talk about this with my students, even at their ages -- they're fairly young, but most of them have experienced racism and the older you get, the more likely you've experienced it multiple times,” Thomas said.

VICTORIA HALL AND JEROME RONO

Montreal resident Victoria Hall told CTVNews.ca that she and her boyfriend Jerome Rono have repeatedly been followed by employees and security guards while shopping in stores. Hall is Haitian and Rono is Filipino.

“Each time without fail, the security guard at Indigo will spot us in the crowd, keep an eye as we browse the first floor. Then when we head upstairs, guess who follows us immediately,” Hall said in an interview on June 3. “I don’t want to have to feel like I can’t go there, but being watched constantly is extremely embarrassing for myself and my boyfriend.”

The 26-year-old said these instances have also happened in other stores where she is “watched like a hawk.”

“At Deserres, I will often wander around looking and touching, which seems to be only allotted for white customers. If there is an empty aisle that I am in, it is quickly filled by an employee that needs to ‘shuffle’ items on the shelves,” Hall said. She added that her most recent experience was at the store’s Atwater location where she was looking for beads.

“An employee came into the aisle and made me uncomfortable by commenting on the fact that I said that the beads were expensive. He followed me as I attempted to find something cheaper around the store or even in the kids aisle. I was so frustrated that I dropped the beads and walked out. I haven’t gone back to that store since,” Hall said.

Rono said in a telephone interview with CTVNews.ca that they always feel pressured to purchase something at these stores to prove to the employees following them that they aren’t there to steal.

“Being followed really puts me in an uncomfortable position, because even when I first walk into an environment, I already feel attacked and not welcome to be there. Sometimes a smile can go a long way, but I actually never get that. I never feel that welcoming,” the 27-year-old said. He added that the couple has boycotted most of these stores following such incidents.

“Having to look at reviews, having to make sure that the place we visit is ‘safe’ and ‘racism-free’ has felt like a new normal,” Rono said. “There’s a certain fear, anger and also confusion that in 2020 we still experience it.”

Rono said they also overhear racist comments directed towards them on their daily commutes. Rono said the first time her experienced racism was as a kid shopping for eyeglasses with his family.

“The salesman claimed that we should get these certain types of glasses because we’re Asian and Asian people have specific kinds of noses... I was a child and this salesperson just threw that comment in without even thinking how it could potentially affect me,” Rono said.

As a Black woman, Hall said that racism is an everyday occurrence for her. She said sometimes racist incidents happen so often to her that they begin to blur together.

“We often think of racism as very physical and volatile, but honestly it’s not those that you necessarily remember. Often it’s the tiny bullets of microaggressions that stick with you. Ignoring your perspective, trying to apply the problems of Black people to all cultures, or not even letting you speak about your issues because ‘everyone goes through these things’,” Hall said.

To get through each day, Hall said she has to put a “bulletproof vest on [her] mind.” She said the microaggressions she experiences are like a “wound that never heals because each day someone adds to that enduring pain and anger.”

“Consistently knowing that someone somewhere is going to stare, maybe a cashier will treat you like garbage for no reason, you soon realize that racism is the small breaking down of your own self-esteem and feelings of safety in the world,” Hall said. “[It] kind of makes you feel like well why would I even bother going out at this point?”

Microagressions may seem like minor incidents to some, but Rono said they can really add up over time.

“Maybe for some people they’ve never experienced racism so they don't consider it a big deal, but racism comes in different shapes and forms from someone looking at someone else differently, saying a comments, or judging a person by how they look,” Rono said.

Hall said protesting is only the first part in addressing racism in Canada.

“I think there's a possibility of making the lives of people of colour, Black people better by having white people align themselves with them and kind of seeing what's happening in their everyday,” Hall said. “Be supportive when you see someone being followed by security guards, take that discomfort that you feel and understand it's magnified ten times more for that person.”

BRIANA GREEN-INCE

Briana Green-Ince, a student at the University of Guelph, said she chose to attend the school in 2016 after attending its open house because the campus had a sense of community that made her feel welcome.

But once she arrived in the fall to start classes, Green-Ince told CTVNews.ca that she quickly noticed microagressions such as snubs or insults happening across campus.

“In first year I went to a party, and they played a song that had the N-word in it and the guy that was playing the song looked straight at me. And then to having the N-word actually said to me… Those types of microaggressions although people think that they're not big things, they actually end up making you feel very unwelcome,” Green-Ince said in a phone interview on June 4.

While that is just one example of racism that occurred at the university, Green-Ince said there are other microaggressions she and others face daily.

“People just may be more discreet about it. There’s so much going on behind the scenes that people don't pick up about or we don't think it's as big of a problem. Like it could be walking down the street... and somebody locks their door when I walk past their car. It's those little things that end up being even worse for society because people get around them all the time,” Green-Ince said

While Green-Ince acknowledges that racism can happen anywhere, she has found that it is especially prominent among university and college students.

“The University of Guelph doesn't really educate their students enough to let them know that these microaggressions are bad and they end up fostering a really non-inclusive type of environment on campus,” Green-Ince said. She added that the administration’ silence on racist incidents on campus forces racialized students to remain silent for fear they’ll make themselves a target for future attacks.

In an effort to change that, Green-Ince has started an online petition for the University of Guelph to make an anti-oppression course mandatory for all students to graduate.

“There needs to be significant change starting from an educational standpoint in the university's curriculum to show that they support racialized students and their voices and will protect them against injustice,” Green-Ince said. “I really hope it inspires not just Ontario students but students across Canada to challenge their universities to make sure that there's an environment where everybody feels safe and everybody feels welcome.”

Green-Ince, who is a psychology and studio art student in addition to being a member of the Guelph Black Student Association (GBSA), has been advocating for Black Lives Matter since the movement started when she was in high school.

“I'm very happy to be seeing that there's so much support and so much outrage that's shared amongst different people all over the world. It’s amazing how much of a difference we can make when we come together as a community,” Green-Ince said. She added that she has attended multiple anti-racism protests across Ontario in the past week.

“It's an overwhelming sense of community when you walk with these people and you see that they're fighting for you. Everybody has different backgrounds and their own different reasons, but they know that Black lives do matter.”

HARJIT SAJJAN

There was a time when Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan thought it would be impossible for someone like him to end up in his current position.

An immigrant from India running the Canadian Forces? He didn't think he'd even be allowed to join the Canadian Forces, at least not if he wanted to keep wearing his turban.

Only when a recruiter at his school told him that the turban wouldn't prevent him from being accepted did Sajjan start to consider the military as a serious option.

Despite rising through the ranks of the military, reaching lieutenant-colonel, and receiving numerous medals and awards for his service before moving into politics, Sajjan was rejected by the first unit he applied to join.

Sajjan said his early years in the military also included plenty of the racism he thought he wouldn’t find there.

"That is when I really realized how intense racism can be," Sajjan told CTV News during an interview that aired as part of a special broadcast about the realities of racism in Canada. "I remember one person … saying to me 'I let you join my military.' Just that position of power and privilege that he was throwing in my face, it just upset me so much."

Sajjan said he believed in himself enough that he vowed to prove his tormentor wrong. He did just that, eventually becoming the first Sikh man to command a reserve regiment of the Army -- without giving up on his dreams, his beliefs or his turban.

Enrolling in the military might have been the catalyst for Sajjan discovering the depth of racial prejudice in Canada, but it was hardly his first experience with racism.

There were insults and slurs as he was growing up, of course. Then there was the realization that Canadians of colour could face serious harm for no reason other than their skin.

That happened one summer while Sajjan was working at a berry farm with his mother. He gravitated toward one of his coworkers – a man who he remembers as being in his 20s and very funny. One day, the man didn't show up at the farm. Eventually word got out that the man had been attacked while walking through a park.

"Later on, we found out that it was actually an attack based on race -- and he was killed," Sajjan said. "That's when it really kind of dawned on me as a kid -- OK, if you're different, all those slurs or things that you hear can actually result in something so bad."

Now that a few decades have passed and Sajjan has become a prominent public figure, the defence minister said he does not feel the need to be on a constant "yellow alert" when out in public, the way he did when he was younger.

But that doesn't mean racism has left his life. Last year, while taking his son to school, he heard another boy making fun of his son's turban. Sajjan said he wasn't used to seeing his son as angry as he was after hearing those comments.

After giving it some thought, Sajjan decided to see the taunts as an opportunity for teaching, rather than punishment. He spoke to his son's class, taking off his turban to show the students the hair underneath, explaining why he wears the turban and why it is important to him, and then retying it.

"Some of us will be able to have that voice, but sometimes … that change happens by leading by example,” he said.

NICOLE JACKSON

As someone who has a light enough complexion to pass for white, Nova Scotian Nicole Jackson said she was often the recipient of some “misguided and ignorant questions” growing up when trying to explain her African heritage to her peers.

“I find because I'm light-skinned, people don't know I'm Black unless I say it,” Jackson said in a telephone interview with CTVNews.ca on June 3.

Jackson said her peers would ask if she is from Africa or if her parents were from Africa and inquire at how Black she was.

“Having conversations about -- OK so if your dad is full Black and your mom's like this much Black, does that mean you're three-quarters Black? -- Just trying to break all that down when really it's just you're Black. But I'm 13, 14-years-old and not really recognizing that as being questionable at the time, just kind of going along with the question,” Jackson said.

She added that she does not feel any ill will towards those who asked her such questions. Jackson said they were just kids at the time and didn’t know any better.

“They were my friends so I don't feel any poor way to them, but that is why this conversation is important because there's varying degrees of racism and some are overt and some are a little bit more subliminal. Reflecting back on it, you always wish you could have said something different, but I can't be that hard on myself being a child at the time,” Jackson said.

However, Jackson says there have been more recent incidents of racism she has encountered. She said in university, some of her white friends would brag about using the N-word or the term ‘monkey,’ not knowing that Jackson herself is Black.

“Another effect of ‘passing’ is that you often catch offhanded remarks or hear people using words they shouldn’t be using because they don’t realize who they’re in the presence of,” Jackson said. “I don't know if that makes them feel more comfortable saying this stuff not knowing that, but it's those little things that kind of add up and affect me.”

As a Nova Scotian, Jackson says these derogatory remarks cut even deeper for her.

“Nova Scotia is home to the very first Blacks in Canada. Many of us do not have the luxury of being able to trace our roots so easily back to our homeland and many of us are mixed, often with Indigenous roots,” Jackson said.

“We come in many different shades, but we are Black.”

Canadian political leaders who do not believe systemic racism exists in Canada like how it does in the U.S. is the “definition of white privilege,” Jackson said.

“There is nothing separating us from the U.S., except a border… [Canada] has a history of slavery, exactly like the U.S. does, and all the same barriers when it comes to education and incarceration.” Jackson said. “It's very short sighted to think that we're different from the U.S.”

SHEILA NORTH

Sheila North, the former Grand Chief of Northern Manitoba, says Canada’s Indigenous people have dealt with racism for generations. In an interview with CTV's Your Morning on June 4, North said it is concerning that some of Canada’s political leaders have said that systemic racism does not exist in the country like it does in the U.S.

“Go meet the mothers and the sisters and family members of the ones that have been taken. It is a very, very sensitive and touchy subject and for people to be blamed and to be so dismissive like that is just reminiscent of what [indigenous people] have been dealing with for many generations and it's very hurtful to hear,” North said.

Despite geographic and racial differences, North said there are parallels between the experience of Black Americans and Canada’s Indigenous people in their interactions with police.

“I'm not going to take away what happened to Black people in America, but it happens every day also to Black people and Indigenous people and people of colour in Canada,” North said. She added that the biggest difference in racism between the two countries is that the recent death of George Floyd was caught on camera.

North said racially motivated incidents are happening everyday to Indigenous people in Canada, but out of the public’s eye.

North explained that she has had her own experiences being on the receiving end of racism since she was a teenager. North said she has been called a “dirty Indian” by strangers on multiple occasions throughout the years.

“Being a young mom with my little kids on their little tricycles and somebody came running out [of their house] saying that they were on their lawn and we weren't, but he was just looking for an excuse and called my kids ‘dirty Indians’,” North said. She said she has also been followed by employees in stores and been accused of shoplifting.

North said the incidents were like a “gut punch” and made her feel horrible.

“You think that you've done something wrong at first, but now I realized that this is a problem that persists,” North said. “Racism is hard and it's hard to deal with, but it's harder to live with it and it does lead to death and we have to find ways to do away with it.”

North said she believes that Canada’s younger generation has the power to change the narrative going forward, but said it will be challenging given how racism has persisted in Canada for generations.

North said anti-racism protests across the world can act as a catalyst for change not only regarding racism facing Black people, but any minority.

“We have to look at finding a way to change policing policies of policing culture, and even government policy. Right now is a perfect time to start changing these kind of policies and regulations because politicians need support from the public to make big changes and right now they have it in a big way,” North said.

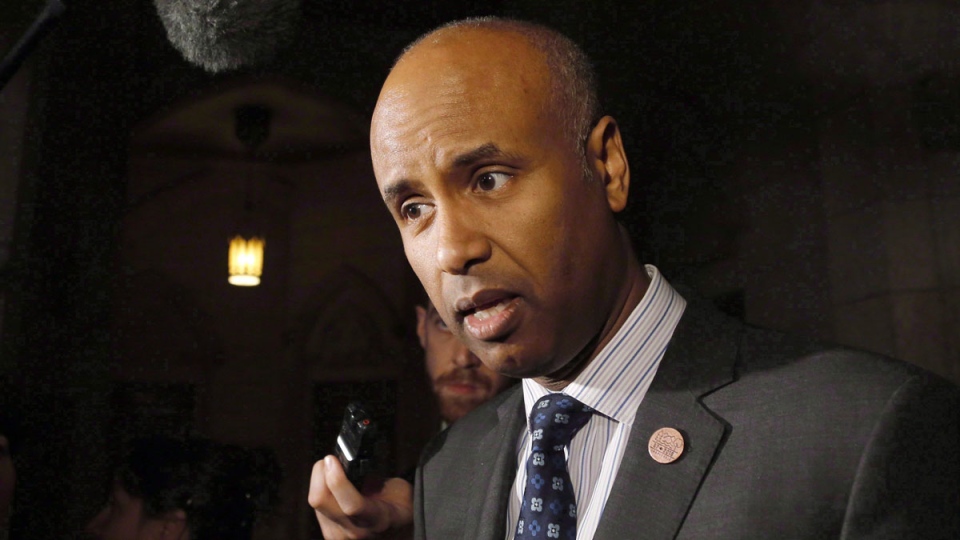

AHMED HUSSEN

Canada's first Somali-Canadian cabinet minister says that, despite his high profile position, anti-Black racism is a part of his life and of so many others, too.

Families, Children and Social Development Minister Ahmed Hussen told CTV's Power Play that, as a Black Canadian, he has a visceral reaction when police vehicles are nearby.

"Instinctively, my back gets up when a police cruiser comes behind me as I drive," Hussen said.

"You just have to look at the history of racial profiling in Canada. It is a reality for far too many young Black men and women."

He said that it doesn’t matter that he is a member of Parliament, nor that he is a federal cabinet minister.

"I still get followed around in stores," Hussen said. He described one such experience, saying that while shopping for cold medicine once with a member of his staff who is not Black, he was followed from the moment he stepped in the store.

"She was surprised that I was being followed around. And for me, I was not. I was not surprised, but it's not about me. It’s about -- this is a very common reality for many, far too many, people in our country and it is important for us to acknowledge it,” Hussen said.

"Anti-Black racism is real. Unconscious bias is real. Systemic discrimination is real. And they happen here, in Canada," he added.

While Hussen said representation in government matters and that those in leadership bear responsibility in this effort, he added that fighting anti-Black racism should be a mission for every person in Canada.

"Diversity is a fact in Canada, but inclusion is a choice. We have to make the choice for inclusion. But it starts with having difficult conversations of the lived, daily reality of dehumanizing anti-Black racism that is experienced by far too many people in Canada. once we have that conversation, once we can listen to those frustrations and those personal stories, then we can move forward," Hussen said.

Hussen said that the first step in addressing these issues is to listen to those who are living the reality of anti-Black racism in Canada.

"I don't want to be in a position where we have these conversations decades from now with my three young sons. I want them to have a better chance to experience shopping, and to experience running in the neighbourhood, jogging, basic things that they shouldn't be afraid to do. That sometimes I’m afraid to do, let alone others,” he said.

Hussen said that having difficult conversations about racism will not "take anything from us."

"If anything, it'll make Canada an even better country than it already is."

KHARI JONES

Canadian football coach Khari Jones says he received death threats while he was quarterback of the CFL’s Winnipeg Blue Bombers because of his interracial marriage.

Jones told CTV News Channel on June 4 that the death of George Floyd was a breaking point for him. Although not one to normally speak out on social media, Jones said he felt he had to join the conversation.

“Just the callous way that it was done and on camera, just like everyone else I was very hurt, I was sad,” Jones said. “I mean there's just been so many and I think people are saying enough is enough.”

The Montreal Alouettes head coach said he received death threats in the form of letters during his career. Jones played for B.C., Winnipeg, Edmonton, Calgary and Hamilton from 1997-2007.

“I think it was just one person at the time but he sent a lot of letters and they were just vile in nature, calling me the N-word, calling my wife names, calling my just-born child horrible names. And then it just got violent and... He said ‘I hope some shoots you’ and ‘Bang you're going to get yours’,” Jones said.

Jones had heard in the past about other athletes receiving death threats but he didn’t expect that it would happen to him, especially in Canada.

“We've had great experiences up here, we've lived all over the country… We've never really experienced that personally from anyone, anywhere we've been, but getting those letters was scary because I was still playing, I was on the road, my wife was home with our new child, and you don't know if the person is serious and going to go through with it,” Jones said.

The person that sent the death threats was never caught, according to Jones.

“It’s something that probably stays with me a little bit because there's someone out there that thinks that way and he knows people, and he has family members maybe that think that same way. Racism is a learned behaviour,” Jones said.

He added that he kept the letters as a “reminder that racism is out there, and to not be complacent and to not think that it doesn't exist.”

“There's someone out there that feels that way and he's probably not the only one. So, it's just more of a reminder than anything else just to make sure that we're careful and we're safe,” Jones said.

However, the threatening letters weren't Jones's first exposure to racism.

Jones previously said he and some friends were wrongly arrested by police, who had their guns drawn, in California in the 1990s. Jones said it was a case of mistaken identity.

Jones said fellow players and couches would agree that there is less racial tension in Canada that in the U.S., but said there’s still work to be done.

“There's still conversations and tough conversations that need to be had. And to get into Black people's shoes, get into minority shoes and to feel what they're feeling on a regular basis because I think people are just sometimes not aware of it. It’s not being arrogant, it's not a thing they're trying to do but they just have to know…It shouldn't be that way,” Jones said.

CHIKA ORIUWA

The second-ever Black female valedictorian for the University of Toronto medical school says she had to overcome challenges and racism throughout her schooling.

As the daughter of Nigerian immigrants, Chika Oriuwa said she felt like she would have to work harder than her peers to become a doctor when she began her studies at the University of Toronto four years ago -- the only Black student in a class of nearly 260 medical students.

“After my undergraduate experience, in which I was also the only Black student, I was very much looking forward to be able to join a medical school, especially at Toronto, which is the epicentre of diversity in Canada, to join a medical school where I could find individuals with a shared identity and shared solidarity, and so obviously, it was incredibly shocking to not necessarily have that when I went to U of T,” Oriuwa explained to CTV’s Your Morning on June 2.

Oriuwa said the online bigotry and racism she encountered regarding her valedictorian title was another example of how anti-Black racism is so pervasive and hard to escape.

“On social media, I've had individuals tell me that I didn't deserve to be valedictorian, that me being valedictorian was simply a political move on behalf of the institution,” Oriuwa said.

In her studies and training, Oriuwa said she encountered racism, including one instance at a hospital when she was mistaken for a janitor. The med student channeled these experiences into spoken word poetry. In one piece, she says “when I step into this white coat, I am more Black than ever.”

Her experiences as a young Black student of medicine also pushed her to activism, hoping she could instigate changes that would diversify the medical school student body and make it better for future Black students to study.

At the University of Toronto, Oriuwa got involved in the Black Medical Student Association as well as the Black Student Application Program, which aims to boost the number of Black medical students.

The program has made progress since Oriuwa was the only Black student in her first year of the program. In the fall’s incoming class, there will be 24 Black students beginning med school -- the largest cohort of Black medical students in Canadian history, according to Oriuwa.

While some progress has been made, Oriuwa said she still faces some challenges.

“On social media, I've had individuals tell me that I didn't deserve to be valedictorian, that me being valedictorian was simply a political move on behalf of the institution,” Oriuwa said.

“That’s why it’s important for me specifically to align myself with the community, especially in times of civil unrest,” she explained.

GEORGE SWANIKER

As an immigrant from West Africa, marketing professional George Swaniker told CTVNews.ca he experienced racism during a job interview in early 2016, only a few months after arriving in Canada.

“I went for an interview for a job with a company in Halifax knowing that I'm very well qualified but as soon as I walked into the room, I instantly realized the mood of the interviewer changed. I think she was expecting to see another person other than a Black person,” Swaniker said in a telephone interview on June 5.

“Throughout the interview, the awkwardness and tone of the entire interview process was so clear, I just felt like quietly walking out,” he added.

Swaniker said he was asked by the interviewer about his thoughts on immigrants coming to Canada to work -- a question he said he wouldn’t have been asked if he was white.

“I really didn't know how to answer this question. I’m an immigrant, having been in the country just a couple of months, and am being posed this question. [I was] being questioned for who I am, for how I look and for where I come from… That question had no meaning and relevance to the reason why I was there for the job,” Swaniker said.

He says he walked out of the interview knowing he would never get that job.

“What may have gotten me into the interview was my name, which doesn't sound African as well my qualifications and experience, but my presence as a Black person blighted any relevance I could bring to that job,” Swaniker said.

The experience made Swaniker feel out of place and unwelcome in a country he has chosen to be his new home.

“I didn't come here as an illegal person, there were rules and regulations, I followed them, and for that reason I'm here so I believe I have a right to be here,” Swaniker said.

Swaniker said he is optimistic that recent anti-racism protests across the world will spur enough change so that his sons won’t have to face similar experiences.

“My hope is that Black people like me as well my children, who are citizens of this country, will be judged not by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character,” Swaniker said.

To address racism in Canada, Swaniker said there needs to be a shift in education for those authoritative positions so they better understand the challenges for racialized people.

“It is better for our fellow native white Canadians in authority to get into the world of people who look different in order to understand them, rather than bundling them together and judging them collectively. We are all different individually,” Swaniker said. “Look at me for who I am and what I bring to make my community and country better rather than the race I belong to.”

Swaniker also said that Black Canadians need to continue to share their experiences with racism to help create that sense of understanding.

“We need to share more of these stories and project them and show that they even exist so we can do something about it. I hope [these stories] will go a long way to help people like me and other people who come after me,” he said.

Edited by Kieron Lang. With files from CTVNews.ca's Jackie Dunham, Ryan Flanagan and Rachel Gilmore.