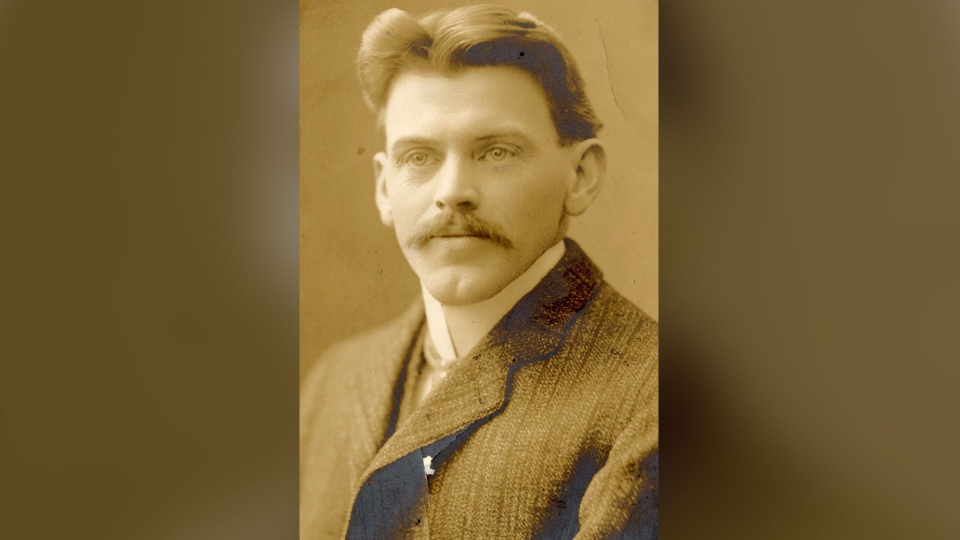

HALIFAX -- Exactly one century after he died, mustachioed train dispatcher Vince Coleman's status as the ultimate Halifax Explosion hero will be cemented Wednesday.

Calgary lawyer Jim Coleman -- Vince's grandson -- will deliver brief remarks during the city's commemorative ceremony to mark the 100th anniversary of the blast that killed or wounded 11,000 people.

The recognition of Vince Coleman is the culmination of his growing legend for his selfless act of saving a trainload of passengers at the cost of his own life.

Halifax now has a condo building named The Vincent Coleman, he was the runaway favourite in a naming contest this year for a new harbour ferry, and his belongings are proudly displayed at a popular museum.

- WATCH: Before the 1917 explosion

- WATCH: 1983 report on the massive blast

- WATCH: Rare images from the aftermath

- PHOTOS: 100th anniversary of Halifax disaster

But Coleman says his father -- Vince's son -- didn't talk much about living through the horror of the Halifax Explosion, and neither did the rest of his family.

"It's amazing how many people have asked me about it, but we don't have family lore," says Coleman.

Coleman's story has enjoyed a revival since the early 1990s, when Historica Canada produced one of its most dramatic "Heritage Minutes," which started with the dispatcher being alerted by a navy sailor that the SS Mont-Blanc, a French munitions ship, was on fire and was about to explode.

As the 45-year-old father of four was about to flee the busy rail yard, he remembered that Train No. 10 was carrying several hundred people from Saint John, N.B., and was due to arrive at 8:55 a.m.

He returned to his telegraph key inside the Richmond railway station, less than a kilometre from where the ship was burning.

Despite the imminent danger, Coleman tapped out a message that warned stations up the line to stop all trains from entering Halifax.

"Hold up the train," the message said. "Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys."

Within minutes, the Mont Blanc and everything near it was obliterated by a super-heated shock wave that caused a tsunami to roll over the waterfront, including the station where Coleman worked.

Coleman's hurried message was among the first to alert the world to the unfolding tragedy. As a result, the Canadian Government Railway was able to quickly dispatch six relief trains carrying firefighters, doctors, nurses and badly needed medical supplies.

"Periodically, we would talk about it, but it wasn't that we really discussed it," said Jim Coleman, whose grandmother Frances died in the 1970s. "When I look back, I find it quite strange."

Coleman, a senior partner with a Calgary law firm, says his father, Gerald Patrick Coleman, was an altar boy taking part in a mass early on Dec. 6, 1917, when the blast hit.

Just after 9 a.m., the ground shook and the church walls fell in, crushing a fellow altar boy.

"All the houses were knocked down," says Jim Coleman, recalling one of the few stories his father told him about that day. "And here he was, this 11-year-old boy, helping to dig people out. It was traumatic. And then he found out that his father had been killed in the explosion and his home was gone."

The blast killed about 2,000 people and wounded another 9,000. Hundreds were blinded by flying glass, and another 25,000 were left homeless. The city's north end was levelled, and much of what was left standing was eventually burned by fires started by upended coal stoves.

As the search for survivors stretched into the night, a blizzard descended on the port city, heaping misery on a community that had already lost so much.

Days later, from deep within the wreckage of the railway station, searchers recovered Coleman's watch, wallet, pen and telegraph key, all of which are now part of a permanent exhibit at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in downtown Halifax.

"You can still see water stains in his wallet," the museum's website says. "His watch speaks grimly of the violent forces which descended on Coleman as its crystal and hands are blown away and its back is pounded in as if by hammers. Coleman no doubt died instantly at his telegraph key."

Jim Coleman says the exhibit holds special meaning for him.

"Seeing the picture of my grandfather and his personal effects, obviously, it touches you somehow," he says.