A new pilot test investigating traces of cannabis and illegal drugs such as cocaine and meth in wastewater from five major Canadian cities appears to show significantly different drug habits from coast to coast, as well as seasonal spikes in the usage of different drugs.

On Monday, Statistics Canada released the results of a 12-month study that looked at levels of different drugs in municipal wastewater samples from Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton and Vancouver. The samples were taken between March 2018 and February 2019.

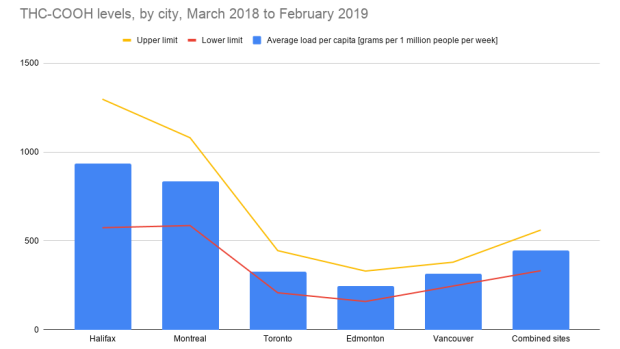

Halifax and Montreal had the highest levels of cannabis use, while Edmonton had the lowest. According to the wastewater results, cannabis use in Halifax and Montreal was 2.5- to 3.8-times higher than Vancouver, Toronto and Edmonton.

The average level of cannabis markers found in the wastewater for all of the cities combined was 450 grams per million people per week.

The study says that it is too early to tell if there has been a significant change in total consumption of cannabis since it was legalized in October 2018.

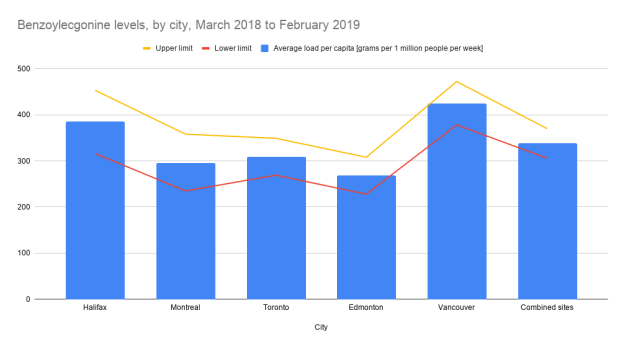

The study observed that there were no dramatic differences between cities in terms of cocaine usage, but Vancouver did have the highest, with Edmonton having the lowest.

High levels of one type of drug in a city’s wastewater did not necessarily correlate to high levels of all drugs in that city -- the results appear to show that cities across Canada have their own individual drug-use profiles.

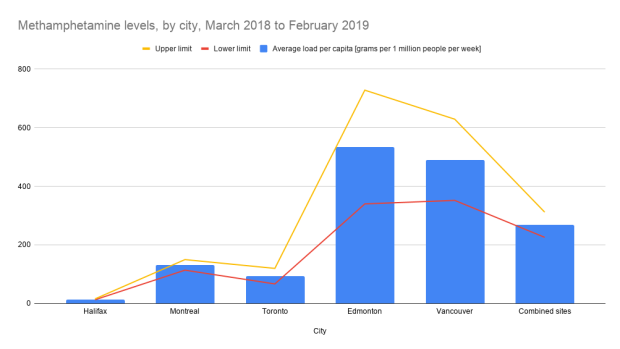

When the study measured levels of meth in wastewater, the difference between the usage in each city was dramatic, with Halifax recording “over 6 times lower than even Toronto, the next-lowest city,” the study reported.

And although Edmonton recorded low levels of cannabis and cocaine, it had the highest level of meth in its wastewater -- slightly more than 500 grams per million people per week. Montreal and Halifax, which had high levels of cannabis, recorded some of the lowest levels of meth.

There were also seasonal patterns to some of the drug usage.

Cannabis use spiked in May, June and December, with May having the highest spike. Cocaine use proved to be highest in the summer and winter, according to the monthly data, and was at its lowest in September and October. The study said there did not appear to be any significant seasonal pattern to meth usage in the Canadian cities studied.

Since the pilot test spanned only 12 months, further study would be needed to see if these seasonal patterns repeat.

There were difficulties in acquiring some of the data, the study said.

When cocaine and cannabis are consumed, the body converts part of these substances into others (a compound called THC-COOH for cannabis, a compound called benzoylecgonine for cocaine) which made it easy for researchers to measure these substances in the wastewater. Meth passes through the body largely unchanged though, meaning that researchers had no way to tell whether meth found in the water had been dumped, unconsumed, or whether it had gotten through a human body first.

For this reason, an extremely large spike of meth in the data for June across all sites except for Vancouver was discarded because researchers couldn’t be sure what had happened to cause it.

The study also measured the levels of opioids in the water, but acknowledged that there were obstacles to measuring each opioid successfully due to how they break down into similar substances. There were also obstacles to accurately measure illegal opioid use versus legally prescribed medications.

Codeine and morphine are frequently prescribed in the health care system as painkillers, but this means their levels in wastewater should be relatively stable. The study found that differences between city levels of codeine and morphine could not be fully explained by provincial differences in healthcare funding.

“Within Alberta and Ontario, where spending is marginally above average, Edmonton has high morphine in the wastewater while Toronto has low morphine,” the study reads. “The low spending in Quebec agrees with the low morphine detected in Montreal wastewater, but the average spending in British Columbia does not explain the high morphine detected in Vancouver wastewater.”

The pilot test posits that these discrepancies could “indicate some level of non-prescribed opioid use.” They emphasize in their conclusions that better data is needed on how many opioids are prescribed in each city, so that the wastewater results could be properly contrasted with that.

The pilot covered more eight million people, around a fifth of the population of Canada, but was not intended to represent Canada’s population as a whole.

“In terms of drug use, the pilot test revealed the potential for seasonal variability in the use of some drugs, including cannabis, cocaine, and codeine,” the study summed up in its conclusion. “Clear differences also emerged in the drug profiles of the different pilot test cities. Cannabis use was higher in Montreal and Halifax, but Vancouver and Edmonton tended to have higher per person use of methamphetamine, morphine, and codeine.”

The study called the “extremely low” levels of methamphetamine in Halifax an “interesting anomaly that should be further explored.”

One of the aims of the pilot test was to see if measuring drug traces through wastewater was possible, and if it yielded meaningful results. The next step would be to work with scientists to refine the data collection process, and repeat the process to see if these results change.