For many people, for many years, working out west was a way of life for those on the East Coast.

But as Alberta’s oil industry began to slow, so too did the careers of a good chunk of those who migrated out to the Prairies. And as the future of Canada’s energy sector remains up in the air, workers are beginning to make their way home.

Among them is Mike MacDougall, a former Alberta worker who returned to Nova Scotia after being laid off.

"The phone rang one Sunday. They said, 'We no longer need you on the project,'” MacDougall recalled. “Two days later, my first girl was born."

For the new father, being out of work was a stark change of pace from the seven-days-a-week schedule he was used to.

“You get up in the morning, go to work,” he said of his old life. “You go home, eat, go to sleep. You get back up and go to work."

Long stretches of work a long way from home is imbued into the East Coast lifestyle, said Nova Scotia rapper Luke Boyd, better known by his stage name Classified. The 38-year-old has a song called “Work Away” on his latest album that depicts the type of routine he says he sees all around him.

"Getting up in the morning when it's still dark out. Kissing the kids goodbye. So many of my friends go out for 2-3 weeks, come home for a week,” he said. “That's been going on for years."

But after peaking at a price of around $140 per barrel in 2008, today, oil has tumbled in value, dropping to around $30.

"Every day you're hearing of people losing assets. Losing homes," said Duncan Campbell, who has now been laid off for over a year.

"I just figured it was a little bit of a waiting game. But it was a long waiting game. I'm still waiting."

Campbell used to work as a construction surveyor out west. Now he’s working at a local call centre as he searches for jobs.

"There's so many people competing for jobs,” Campbell said. “Right across the country. It's tough."

And the tough times don’t have a clear end in sight. Business professor Doug Lionais said low prices are going to last for an extended period of time -- possibly even dipping lower than they already are.

The effects of a slumping Alberta are being felt in the east as well, he said.

"Construction, housing, our retailers, restauranteurs. They're likely already seeing some of this impact."

Lionais said these situations hurt not only individuals involved in the industry, but society as a whole. Mental health issues, he said, tend to be associated with economic troubles.

“We see issues, unfortunately, of addictions. Domestic violence. Crime. These things can be associated with these types of downturns."

Campbell is guardedly optimistic that things will get better. But he’s not holding his breath for a full return to normal.

"I think things will rebound,” he said. “But it seems every time there's a downturn, things never come back the same."

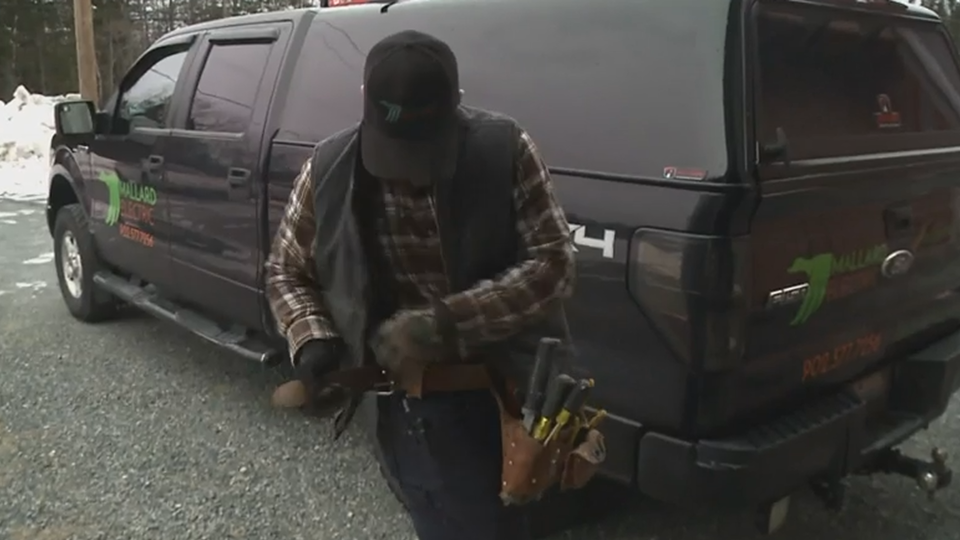

And then there’s MacDougall, whose daughter is now eight months old. Although he was pulling in $150,000 a year out west, he doesn’t intend on trying to return to that life.

He now owns his own electrical company in Cape Breton.

"I just basically pulled the trigger,” MacDougall said. “I said I want work for myself, I want to have my own company."

He says he enjoys the freedom of his new job, not to mention being close to his family.

“It's a cool feeling because now every time when you're driving home, you always think, 'I wonder what my little girl learned today.'"

His wife Stephanie agrees.

"He'll be able to be here for birthdays,” she said. “We won't have to wait the extra week to cut the cake."

As MacDougall works away without having to be away from work, Boyd hopes others in his community will be able to enjoy similar successes. Ideally, he said, his lyrics won’t be quite as relevant down the road.

"Hopefully it will bring back memories of, 'Hey, remember when we had to leave Nova Scotia for work? But now we're here, we’ve got jobs.’"

With a report from CTV Atlantic