TORONTO -- Class actions are an ever-more common means for groups of people to fight for compensation for damages and frequently made the news in 2019. Here’s how they work.

What is a class action?

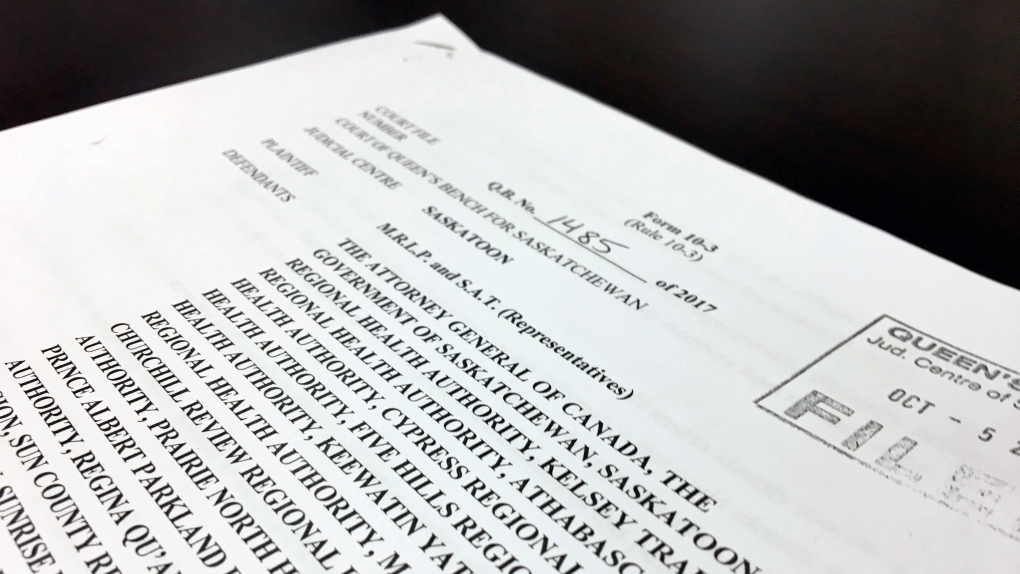

Class-action lawsuits allow groups of people to seek justice against a defendant who is accused of causing loss or harm to others through product liability, privacy breaches, consumer protection issues, environmental accidents, mass personal injury, institutional abuse, and labour and employment issues.

They are usually brought by one individual on behalf of many people, with one plaintiff acting as a representative for the class. Class actions are often lengthy, complex and multinational cases.

The concept of representative litigation dates back to medieval England but the modern class action took shape in the U.S. in the 1960s, largely to address civil rights, says Jasminka Kalajdzic, an associate professor of law and director of the Class Action Clinic at the University of Windsor. It has been an effective tool for systemic change and is still used to assert minority rights, such as the protection of migrants and veterans, for instance.

In Canada, class actions were first codified in Quebec in the 1970s, with Ontario following in 1993. Now, all provinces except P.E.I. have a class action procedure.

The Law Commission of Ontario estimates there have been approximately 1,500 class-action lawsuits launched in Ontario in the last 20 years and that in recent years, about 100 are initiated annually. There is no database of Canada-wide cases.

“Legislators and jurists in Canada have had a clear vision of how class actions should work and have come up with a strong and beneficial mechanism to help those who have been injured or harmed,” says class action lawyer Evatt Merchant. “It’s a fair and equitable system.”

How are class actions initiated?

In some cases, an individual goes to lawyer with a complaint of harm caused by another, but in many cases, it’s law firms determining there is a problem and finding someone affected who is willing to be the public face and act as a representative litigant, says Kalajdzic.

Class actions are expensive to litigate, so lawyers have to believe in the merits of a case, be confident it meets the requirements to be certified as a class action, and that its potential compensation is worth pursuing the lawsuit.

The class must be represented by a lawyer. Compensation for the lawyer primarily comes through a contingency fee, meaning they only get paid if the case settles or if it goes to trial and the plaintiffs win. The lawyer gets paid a percentage of what the class wins. “Courts are reluctant to award more than one-third of the settlement to a law firm. Compensation is being closely monitored by courts,” said Kalajdzic, who practised class-action law for 10 years before turning to academia.

What is certification?

A court must certify a proceeding as a class action through a certification hearing, along with approving a representative litigant and the parameters of who is a member of a class. That could be the owner of a particular car made in defined production years, an employee of a company during a specified time, or the holder of a particular credit card, for instance.

Who's in the class?

“It’s a common misconception that you have to sign up or register to be part of a class, but Canada has an opt-out system,” said Kalajdzic.

If a person is covered by the definition of a class and wants to take part in a class action, there is no action to take. But if they want to preserve their right to pursue an individual case, they must opt out of the class action by a prescribed date following certification. Without opting out, all those covered by a class action are bound by its result.

Where do the numbers come from?

The largest class-action payout to date was the Indian residential school settlement of $1 billion. Next was the $290 million awarded to Volkswagen owners over the emissions scandal.

Lawyers often pick a compensation dollar figure the class is seeking out of the air, says Kalajdzic. “It must be larger than what the plaintiffs could reasonably get at trial, because procedurally, you can’t get more at trial than what you asked for. But at the early stages, they don’t have all the information needed to really come up with a solid number. So it’s usually set really high at the outset.”

How are settlements dispersed?

The advantage of the Canadian class-action system is that compensation is not limited to those who contact a lawyer, says Merchant, whose firm has pursued class actions against retailers, cell phone companies, car companies, medical device makers, toy companies, pharmaceutical manufacturers and the federal government.

Anyone who fits the definition of the class can apply to be part of a settlement.

In large class actions with a wide class, the settlement process can be very long and drawn out. A court will prescribe the period during which members of a class action must make a claim on a settlement. Individuals must provide proof at that time that they fall within the definition of the class and the extent of their injury and damages suffered.

A settlement fund is handled by a court-appointed administrator and money is dispersed objectively, based on significance of injury, not when a class member jumped into the class action, says Merchant.

Where to turn for help

The law school at the University of Windsor launched the Class Action Law clinic in October to research class actions, develop policy proposals, and help people navigate the system and understand their rights and obligations. Lack of English language skills or inability to use a computer can shut people out of the system, says Kalajdzic. Failure to file paperwork correctly or on time could mean an individual forfeits any claim from a settlement, for instance.

After Kalajdzic published research into access to justice for class-action members, she started getting calls for help. People didn’t know where to turn for information or advice and Kalajdzic determined there weren’t many options.

“It was apparent there was an information gap. The size of class actions means it’s impossible for the lawyers involved to give one-on-one personal advice to everyone who needs it.”

Demand is so strong at the clinic that it is adding staff in January.

“It’s really gratifying to see the number of individuals who are contacting us for assistance. We’ve already been approached by organizations and law firms to consider legal interventions on appeal cases.”

Calls for reform

The Law Commission of Ontario released a report in September urging 47 changes to improve access to justice and the efficiency of the class-action process, better protection for class members’ interests, and more scrutiny and justification for counsel fees.

Kalajdzic, who was a principal researcher on the two-year study, says one of the biggest issues with the system in Ontario is, unlike other provinces, the loser pays the winner some portion of the legal fees.

“There are some good reasons for that system because it deters frivolous litigation, but the downside is too high in deterring strong, meritorious cases,” said Kalajdzic.

“The people we consulted in legal clinics who work with community groups said they might otherwise use class actions to advance anti-poverty or human rights matters but they can’t take on the risk of paying the defendant’s legal costs.”